Imagine, if you will, the following scene playing out on a television screen: A trial is underway in a courtroom. The defendant is being cross-examined by a sharp-dressed lawyer, who lists the felonies and misdemeanours the defendant has been charged with in the past. The lawyer also mentions that the defendant is behind in his alimony payments. The defendant takes umbrage at these comments, and lashes out verbally at the lawyer. The judge bangs her gavel in response, calling for order.

Scenes similar to this one have appeared in hundreds of television series. Unfortunately, when such a scene appears in a Canadian series, it typically contains some or all of the elements described above, which are factually inaccurate in a Canadian context. Canadian judges assert control over proceedings verbally rather than by using gavels. There are no felonies or misdemeanours in Canada; instead, individuals are charged with indictable, summary conviction, or hybrid offences. Canadians do not pay alimony; the correct term is “spousal support”. Even the sharp-dressed lawyer may be inaccurate, as many courts require lawyers to wear a robe that obscures their clothing.

Fig. 1: As a series set in British Columbia, Family Law should not have put a gavel in judge Chip Crombie’s hand.

Of course, it is not only legal procedures and terms that are presented inaccurately on television. Every show that features a character crawling through a ventilation shaft without issue is either intentionally or unwittingly ignoring the fact that one or more of the following characteristics apply to most ventilation systems: too small to accommodate a human being; dirty; has sharp screws sticking up through the crawling surface; filled with rapidly rushing air. Steven Moffat’s predilection for writing scripts in which characters, such as Sherlock Holmes in Sherlock (2010-2017) and the Doctor in Doctor Who (1963-1989, 1996, 2005-present), are described by themselves or others as “sociopaths” or “psychopaths” suggests a lack of understanding of the terms. If they were truly sociopathic/psychopathic, they would lack the ability to care about anyone, but their protective behaviour toward those closest to them (such as the Doctor’s various companions and Sherlock’s associates Dr. Watson and Mrs. Hudson) indicates that they care deeply about at least some people.

Fig. 2: Detective Jake Campbell in Sight Unseen is one of many television characters lucky enough to find a clean ventilation shaft that is free of hazards and air currents and that fits him to a tee.

Of course, the obvious rejoinder to such factual errors is “It’s just a TV show!”, and there are many points that support that response. First of all, fiction-based television series exist primarily to entertain, not educate. If the viewer wishes to watch something in which everything is true-to-life and therefore can be learned from, then there are plenty of documentaries and non-fiction programs on offer. Moreover, if the series in question is, by its very nature, far-fetched, then surely both the audience and the people working on the series are engaging with the show precisely because it offers an escape from reality. If the audience is willing to suspend disbelief and accept over-the-top scenarios such as, for example, the lawyer in the scene presented above being a werewolf, then it seems a tad silly to quibble about her court attire not being presented accurately in what is clearly a fantasy world. In addition, scriptwriters sometimes intentionally eschew facts to serve the plot. A writer may alter a city’s layout so that all of the story’s locations are close together, or tweak the skillset of a particular profession to give a character the abilities needed to solve a problem. Intentional fictionalisation is also used to avoid legal issues that might arise from using the names of real institutions or individuals. For example, the Surrey, British Columbia-set police drama Allegiance (2024-present) features characters who work for the Canadian Federal Police Corps, while the Canadian medical drama Transplant (2020-2024) follows the doctors who work at York Memorial Hospital in Toronto. As neither entity exists, the writers are free to craft plots about the characters without inviting accusations that they are ruining the reputations of real-life police or health care workers. Furthermore, the benefits of ensuring complete accuracy are, at times, vastly outstripped by the costs. Film and television makers often proudly flaunt their dedication to accuracy via anecdotes about, for example, their consultations with an expert in a long-dead language to ensure that the writing on an ancient relic in the background of a scene is completely correct. These stories often end with the expert pointing out that a grand total of three people on the planet would have been able to tell if the production had foregone the consultations and just made something up. Such commitment to accuracy is commendable, but one could argue that the resources required to achieve such infinitesimal gains would be better used elsewhere on the production.

Fig. 3: Allegiance opted not to namecheck the Royal Canadian Mounted Police or any real-life provincial or municipal law enforcement agency.

While we have identified good reasons to get things wrong, there is also a case to be made for ensuring a level of factual accuracy in television series. Let us return to our legal example. While legal inaccuracies are far from the only factual issues that plague Canadian or any other country’s television shows, they are some of the most prevalent ones due to the high number of law-related series produced. In Canada alone, law/police dramas currently in production include the aforementioned Allegiance, Family Law (2021-present), Law & Order Toronto: Criminal Intent (2024-present), Murdoch Mysteries (2008-present), and Sight Unseen (2024-present). This does not take into account non-law-themed series that use legal terminology in dialogue. Though these shows are written, produced, directed, and performed by Canadians, it is not uncommon for them to feature characters talking about “committing a felony” or “paying alimony”, gavel-banging judges, or lawyers wearing business attire rather than legal robes. The presence of these errors in Canadian productions indicates that the Canadians working on them are ignorant of the differences between their legal system and the American one they see depicted on TV, and perpetuates misconceptions amongst the viewing public. A factually accurate series, in contrast, educates its creatives, as evidenced by this comment by Tassie Cameron, showrunner of Law & Order Toronto: Criminal Intent: “There are…some things about the Canadian system that are different…In the court scenes…our background players are in legal robes. You would never see that in the US version. Also, in Canada, you don’t automatically have the right to an attorney at your interrogation. I was really surprised by that, but it’s a misconception many of us picked up from watching American television.”

Fig. 4: Because the Law & Order Toronto: Criminal Intent production team did their homework, Deputy Crown Attorney Theo Forrester and his peers are properly robed.

The ability of a factually accurate television series to educate the production team, and, consequently, viewers, and thereby correct misconceptions that it would otherwise perpetuate is a not inconsiderable thing in today’s world of misinformation and disinformation. Another point in favour of ensuring factual accuracy is that, unlike a long-dead language, many of the facts that television shows get wrong are not obscure, meaning that the costs to research them are low and vastly outweighed by the benefits of the population at large learning correct information about something they encounter in daily life. Those benefits are amplified by television’s broad reach, with innumerable chances to drive a correct fact home offered across the days, weeks, months, and years that a television series runs. In contrast, the other side of that broad reach, namely the ability of a series to spread and reinforce a factual inaccuracy dozens or hundreds of times across a run that may span years, should give creatives serious pause before dismissing fact-checking as a waste of time and effort.

If the facts in question, such as the legal ones being discussed, are country specific, a television series’ accurate conveyance of them can play a nation-building role by highlighting the distinctiveness of the country’s values and societal and government structures. By accurately conveying country-specific facts, television series can also teach people how to navigate their own country and its institutions. With the number of self-represented litigants on the rise and slowing down proceedings as they stumble through the justice system, might things be made ever-so-slightly easier for both the litigants and the judges walking them through court processes if everyone arrived with an accurate idea of how a Canadian courtroom looks and works?

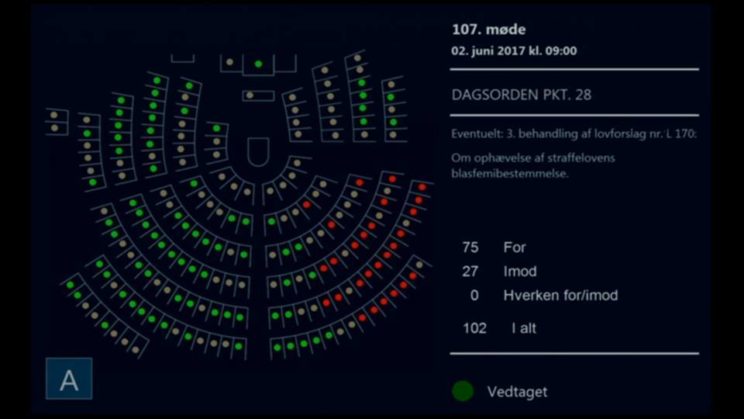

For those watching in another country as part of the global streaming audience, viewing a series set in a different country might be as close as they come to visiting it or interacting with its people. Would it not be better if those viewers received an accurate depiction of the origin country, one that dispelled stereotypes and introduced them to a new society, culture, and system of government? I have never been to Denmark, but, when watching the political drama Borgen (2010-2013, 2022), I was fascinated by even the tiniest details of its parliament’s workings, such as the electronic voting board that showed how each member voted. A bit of research confirms that the voting board does, in fact, exist, but, if neither I nor the production team had bothered to check, I could have operated under a misconception about the country and passed it on to others. As not every audience member will do their due diligence regarding everything they see on television, it is important that shows depict countries accurately in order to avoid negative repercussions from misrepresenting them to the world at large.

Fig. 5: Proof that the Danish parliament’s electronic voting board exists!

Television cannot be expected to replace schools or universities, nor should it be required to be dryly factual to the point of stifling creativity and reducing entertainment value. However, if television production teams make the effort to get broadly applicable facts right when creative or legal issues are not at play, the result can be a richer viewing experience for all that does its part in the misinformation fight.

JZ Ferguson is an enthusiast of British popular culture with a particular affinity for television series of the sixties and seventies. She has written for all five, and co-edited two, of the volumes of The Avengers on film series. She has also written for the Classic British Television Drama series, penning chapters on shows such as The Saint, Danger Man, The Persuaders!, and Gideon’s Way. Other volumes featuring her work include Man in a Suitcase: A Critical Guide, Swinging TV, Survival TV, New Waves, and A TV Box of Delights: A Golden Age of British Children’s TV. Escapades: An Exploration of Avengers Curiosities, co-authored with Alan Hayes, is available now from Quoit Media. She lives in Canada.

Oh – what a brilliant read! And with such a great sense of purpose. When my wife and I watch ‘imported’ shows, it’s the differences in culture and procedures (which we *hope* would be an accurate representation of the country) that often engage us the most… with “Borgen” being a prime example. And how fascinating to learn about another little cache of Canadian shows at a time when I’ve only just caught up with “Seaway” and *still* haven’t seen all the episodes of “Seeing Things”.

Many thanks! Enjoyable, informative and thought-provoking! 🙂

All the best

Andrew