The face of independent TV production in the UK has changed irrevocably. 21st Century Fox and Apollo Global Management together have taken over Endemol, Shine Group and Core Media and will transform them into the world’s first mega-indie. According to Broadcast (10 June 2014) “The shape of all three production outfits will be carefully considered after Fox and Apollo last week announced plans to create a joint venture housing the businesses – a decision prompted partly by top-level market consolidation in recent months.”

The recent spate of mega-mergers, involving financing from the heart of the US industry, is the end of a long process of transformation. At the beginning of the 1980s, Channel 4 brought a new model of TV production to challenge the vertically integrated broadcaster-producers, both public and private. Channel 4 aimed to deal with around 500 different companies every year, sharing its largesse so no grouping would grow too big. Disaffected radicals from within the broadcasting monoliths flocked to this new model, born from a heady mix of seventies leftism and Thatcherite free market ideas in equal measure. I outlined this in Screen, Autumn 2008. By the end of the 1980s it was clear that Channel 4 was behaving more like a business, with the whip hand over a legion of small suppliers with no alternative place to sell their ideas or expertise.

So the independents embarked on a sustained political campaign, first to supply BBC, ITV and other broadcasters, and then to retain more control over their intellectual property. My first contract negotiation with Channel 4 had, after all, started out with Channel 4’s basic terms: Channel 4 will own the programme for the entire universe in perpetuity. Things got better than that, but not much. As a part of the campaign for independent producers to retain rights in their productions, I thought that this would end up with the existing independents (by then including several groups making hundreds of hours a year) in partnership with a new breed of distributor/financiers along with lines of the film industry. They would provide a level of finance (secured against potential international revenues), alongside the broadcasters’ purchase of a licence to use the programme for a defined number of times over a defined period. But this did not happen.

Independent companies did indeed win the right to keep the basic property rights in their programmes. Production financing moved to a licencing model where broadcasters paid a defined amount rather than the 100% that Channel 4 had done in the heady early years. But no distributors emerged. Instead, the larger independents sought city finance and set up their own distribution arms, or contracted out their programme sales to traditional sales houses, rather than financier-distributors. Perhaps, they learned the lesson of Hollywood cinema independents and the lack of financial returns that they normally see from their distributors.

This forced the independent sector to consolidate, and fast. Two models were adopted. One was a merger model, to create large companies producing thousands of hours across Europe. Endemol is the obvious example. The other was to seek various forms of confederation, from the ‘friendly investor’ model of Wall to Wall and Shed (with Warners as distributor), to the acquisition of independents by well-financed, purpose designed groups like All3Media or Bob Geldof’s Ten Alps. Their business model allowed the former independents to continue to work as separate entities, but with explicit targets, a shared culture in the areas of business systems, distribution etc, and direct access to the group’s investment funds.

Both models work, but they are different. According to Broadcast “Relief seems to have been the over-riding emotion among senior All3Media execs when Discovery and Liberty Global’s joint takeover [of the company] was sealed last week… Without being too blunt, some of the reaction was based on self-interest. Had Fremantle Media bought All3 (or Warner Bros or NBCU, for that matter) it would inevitably have had production systems and ways of working that it would have wanted to impose. Certain job functions would have been doubled up, especially centrally, resulting in redundancies. Key execs … may well have left. Instead, by selling to two companies that aren’t really in the production sector in a meaningful way, those issues have been avoided.” (15 May 2014)

Why did these issues of group organisation matter so much to All3Media? The company was founded by former ITV executives Steve Morrison and David Liddiment, people who understand the impact of production organisation on what it produces. They clearly believe that the long-term sustainability of production innovation depends on their federal structure. And here we come to the key to the success of UK programming in the international market, and in particular in the international market for TV formats. This success comes about because the UK production industry offers something distinctive. Its formats, especially in the popular infotainment and reality TV sectors (food, lifestyle, social issues) are informed by a public service ethos. Motivated by a degree of interest in, and even respect for, their subjects that is not shared elsewhere, UK formats tend to be more sustainable in the long run.

The issue of the fundamental values of the UK production culture is crucial to its long-term sustainability. James Bennett’s research into the promulgation of public service values within UK broadcasting’s independent suppliers is important in understanding how this process works. The continuing presence and involvement of the BBC in particular has an absolutely key role. It may seem to the observer of the UK production scene that the development of mega-indies renders the BBC’s own future problematic. In fact, the opposite is true. The BBC and its public service ethics are key to the long-term sustainability of the UK independent production business. Part of All3Media’s fears about a possible takeover by Freemantle are the result of a concern that their federal structure enables discussion of, and promulgation of, public service values. Not coincidentally, it closely resembles the positive elements of the BBC: its organisation into strong departments with their own cultures. Difficult to manage, yes, but essential for the onward development of public service values in practice.

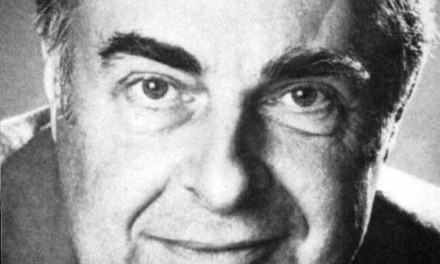

JOHN ELLIS is Professor of Media Arts at Royal Holloway University of London. He leads the ADAPT project on the history of technologies in TV, funded by a €1.6 million grant from the European Research Council. He is the author of Documentary: Witness and Self-revelation (Routledge 2011), TV FAQ (IB Tauris 2007), Seeing Things (IB Tauris 2000) and Visible Fictions (1984). Between 1982 and 1999 he was an independent producer of TV documentaries through Large Door Productions, working for Channel 4 and BBC. He is chair of the British Universities Film & Video Council and also oversees the Royal Holloway team working on EUscreen. His publications can be found HERE.