In the current febrile atmosphere of the debate about whether the UK should be “in” or “out” of Europe, it is interesting to look back at how TV has shown and shaped our relationships with other countries. I have previously written about how, across the developed world, there are constructions of childhood and children that have been similar enough to facilitate the exchange of programmes within the category of “children’s TV”. That suggests we could compare childhoods, on the basis that they are both similar yet different to each other. Here I want to discuss a concrete example in which the very form of a programme is comparative, and relies on an institutional network of international programme exchanges for its existence. This was a programme about children, for children, that explores comparative versions of childhood.

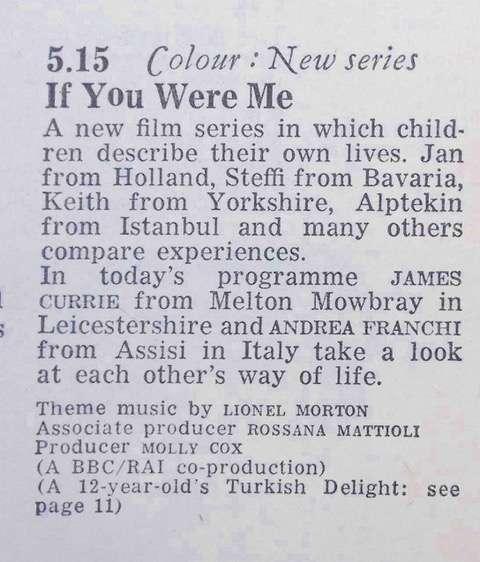

The series If You Were Me was screened sporadically on BBC1, starting on 3 February 1971. It was scheduled at 5.15 pm, at a time when most children would have recently returned home after school. In total there were 22 half-hour episodes, shown in 1971, 1972 and 1975. The premise was summed up in the strapline printed in the Radio Times, “You stay in my house I’ll stay in your house. You sleep in my bed I’ll sleep in your bed. You come to my school I’ll come to your school …”. Thirteen-year old boys and girls from different countries swapped lives, and were filmed at home and at school.

The If You Were Me signature tune by Lionel Morton featured on his eponymous 1973 album.

The programme was a co-production, whose films were made in collaboration with European Broadcasting Union members who showed them in their own national territory, with translated voice-over. The broadcasters who made the films came from all around the European continent and beyond, and included AVRO (Netherlands), Bayerischer Rundfunk (southern Germany), BBC in Britain, CBC (Canada), RTB (Yugoslavia), RTT (Tunisia), PBS (USA), RAI (Italy) and TRT (Turkey). Each of them was the major public broadcaster in their territory.

The producer was Molly Cox, who worked on the BBC story-reading series Jackanory in 1965-66, and later on the series Why Don’t You Switch Off Your Television Set and Go and Do Something Less Boring Instead (1973) which featured film segments authored by children themselves. The director was Tim Byford, who worked on the staff of BBC’s Children’s Department, directing film segments about children’s lives for the magazine programme Blue Peter but who moved permanently to Yugoslavia in 1971 after going there to film one of the episodes of If You Were Me.

The Radio Times listing for the first episode

Short runs of episodes were made, beginning with six films. In the first episode, James Currie from Melton Mowbray in Leicestershire swapped lives with Andrea Franchi from Assisi in Italy (February 1971, repeated in July 1971). In the following week, Nicola French from the village of Swanmore in Hampshire exchanged with Milica Zaric from a Serbian village in Yugoslavia. That programme was repeated in July 1971 and again in 1972.

In the third episode, Keith Powell from Rawmarsh in Yorkshire swapped with Kamel Khalfallah from Dar Cha Bane in Tunisia, and this film was also repeated in 1972 and 1975. On 24 February 1971, Campbell Aiken from Aberdeen in Scotland exchanged lives with Jan Oosterbroek from Hoorn in Holland (repeated 1972). In the episode from 3 March 1971, Jane Curtis from the village of Lavenham in Suffolk swapped with Stephanie Kranz from a Bavarian village in Germany. In the final episode of the first series, on 10 March 1971, Nicola Snook from Bath exchanged with Ginger Gonzales from Salt Lake City, Utah, in the USA.

The intention was to show the diversity of children’s lives, and also the potential equivalences between them. So, for example, children who came from villages swapped lives with village children from the other country, and the ages of the children were similar (not least because they were integrated into the school systems of each country). In each programme a British child travelled, so the overseas children were always seen in relation to a UK childhood that was the measure of comparison.

The second season of If You Were Me was from April to the late summer of 1972 when repeated programmes from the previous year were supplemented by some new films. These were from countries that were mainly further afield: on 16 April 1972, David Jolley from Plymouth exchanged with Julie Billoch from San Juan, Puerto Rico. The following week, Carwyn Bell from Felindre, Swansea, swapped with Michel Cochrane from Quebec City, Canada. On 7 May 1972, Kevin Hawkesworth from Boston, Lincolnshire, exchanged with Felipe Morales from Jalapa, Mexico. The final new film that year was on 20 July 1972, when Nicholas Turpin from Bristol exchanged with Alptekin Oktayer from Istanbul, Turkey (and this episode was repeated in 1975).

If You Were Me was conceptually linked to the concept of Town Twinning, on which school exchange schemes and pen-friend relationships between children were often built. Although twinning only gained state funding from the EU in 1989, it had been running since 1947 to foster friendship and understanding between different cultures and between former enemies after the Second World War, as an act of peace and reconciliation and to encourage trade and tourism. It was a high-profile means to create European identity by acknowledging and repudiating national conflicts, featuring twinning between cities devastated by war. One twinning was between Coventry (UK), Dresden (Germany) and Stalingrad (USSR), for example. Of course twinning not only concerned children, but their mobility and communication between countries was a concrete instance of the scheme.

It was the infrastructure of the European Broadcasting Union that made If You Were Me possible. The EBU was formed in 1950 by 23 broadcasters across Europe and the Mediterranean, and further national members and associate members subsequently joined (some of them outside Europe, such as broadcasters from Canada, Japan, Mexico, Brazil, India and the USA). The unstated assumption was that childhood was interesting to a multinational audience, and comprehensible to them as a shared concept. The notion of “childhood” was a currency that was exchangeable across borders. Like currency, it was nationally distinctive but the childhood of one country could be compared with that of another. In 1971, the year that If You Were Me began, the Eurovision network broadcast Children of the World, hosted by US actor and UNICEF ambassador Danny Kaye, which presented segments representing children’s lives in 45 countries, using 22 land stations and two satellites.

The circulation of children’s television across borders has drawn on transnational conceptions of what childhood is, and the child audience has been constructed as a transnational entity that could be addressed and provided for by transnational programming. On New Year’s Day 1973, a few months after the second series of If You Were Me, the UK joined the European Economic Community. And in the Summer of 1975, a referendum confirming the UK’s membership almost coincided with repeats of selected episodes. I remember the programme quite well, though it now seems to be “lost”; this might be a good moment to find the series and show it one more time.

A version of this text was first presented at the workshop ‘Transnational Histories of Children’s Media’ hosted by Dr Helle Strandgaard Jensen, at the University of Copenhagen in December 2014.

Jonathan Bignell is Professor of Television and Film at the University of Reading. His writing about television drama, film, Action Man, Barbie and Samuel Beckett is listed on this web page. Some of it can be downloaded freely in Open Access from there and some other material is available from Academia.edu.

We only acquired a television in the summer of 1970 and “If I Were You” was one of the first children’s programmes I remember (along with “Catweazle”, “Blue Peter”, “Magpie” and “Time Slip”) and it resonated with me and began an interest in travel, languages and foreign lands.

I can’t remember much of the content, however, the format was factual and quite grown up for a children’s TV programme.

Hooray ! At long last I’ve found one of my favourite programmes. I couldn’t think of the name of it so until It appeared on genome.ch.bbc.co.ukschedules/bbcone/London/ featuring issues of the Radio Times from way back, I wasn’t having any joy. I could have sung the theme tune for you though ! nobody else seemed to have heard of it of my age either ! Now all I need is to to be able to play the tune to my husband so he knows I easn’t making it up !

I’ve just discovered the episode featuring the swaps from Nicholas from Bristol and Alptekin from Istanbul . . .

cstonline.net//cstonline.net//www.youtube.com/watch?v=duPOvbArvPU&t=270s

Thank you Andrew, I searched for ages but could not find a complete episode from “If You Were Me”. It’s great to see this example.

My son Keith Powell who was teamed with the boy from Tunisia, became a talented musician. He became an Army Bandsman. Sadly he was murdered by the ira 20 th July 1982 on the Regent’s Park Bandstand. He was 24 years old.

Hi Mrs Powell. I loved this programme. It seemed to come from a different, golden age when we were all so much more innocent than today. That’s probably hindsight, but it was a big part of my childhood. So, so sorry about your son. What a horrible conflict that was!

I believe that my older brother was the penfriend of said Milica Zarić!

Milica is referred to at one of my Blogs, ‘Girls Of The Golden East’ in a post dated 26th May 2021 entitled ‘The Sun and Venus’, where her love of the Dutch group Shocking Blue is talked of – of which my brother was aware at the time. I wonder if Tim Byford is ever in contact with Milica nowadays as it would be incredible if ever she became aware that her former penfriend’s younger brother has a perhaps unique Blog about the female Pop music of the satellite nations of the former Soviet Bloc!

I actually have a clear memory of the edition that first went out on the day after my eleventh birthday as I recall Alptekin Oktayer going to a match of Nicholas Turpin’s beloved Bristol Rovers at the old Eastville Stadium. Perhaps there is a Bristol Rovers Fan Club somewhere in Istanbul!

Looking at the date this article was published is quite unbelievable for me, BTW. It was the day I left Belper for my first-ever trip to Slovakia in connection with my Blogs, the night of 4th to 5th March 2016 being on the Harwich – Hoek van Holland ferry! The journey on 7th March from Bratislava to Michalovce, the home town of the Valérie Čižmárová for whom I run the Fan Blog, ‘Hotlips On The Horse Tram’, was one of the most memorable days of my life and it’s documented in a series of videos taken from the train at my YouTube channel linked from both ‘Girls Of The Golden East’ and ‘Hotlips On The Horse Tram’.