Last year, Ian Greaves wrote an illuminating CST blog about the ‘turmoil’ COVID had created for the film journal Sight & Sound. As Greaves discusses, lockdown saw the return of extended reviews of new television in Sight & Sound with a separate television reviews section starting in Summer 2020. It was not really surprising therefore that, later in 2020, the magazine publicised Small Axe which in the UK was screened in the Sunday night slot on BBC ONE (ie the mainstream, general channel) for five nights, starting on 20th November. It was however notable that Sight & Sound treated Small Axe as five standalone films rather than as a major television event in the UK. Significantly, Sight & Sound decided that the separate episodes should be eligible for inclusion in its famous ’50 Best Films Poll’ for that year. As someone invited to take part in the (smaller, only 20 Best) television poll, I can say that I was thereby barred from voting for Small Axe. That was infuriating and so I decided to explore this situation a bit further. Hence this blog.[i]

Film or Television?

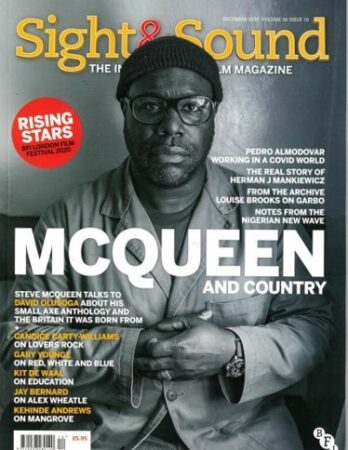

Sight & Sound certainly gave Small Axe exceptional coverage at the time of transmission. Vol 30: issue 10 (Dec 2020) (fig 1) celebrated Small Axe extensively: through an Editorial by Mike Williams; a McQueen interview with David Olusoga; reviews of all five episodes by celebrity reviewers (Kehinde Andrews on ‘Mangrove’; Gary Younge on ‘Red, White and Blue’; Candice Cary-Williams on ‘Lovers Rock’; Kit de Waal on ‘Education’; Jay Barnard on ‘Alex Wheatle’); and standard reviews in the film reviews section of ‘Lovers Rock’ and ‘Mangrove’.

The next edition, Vol 31: 11 (Winter 2020/21) (fig 2) was the issue which announced the results of the two polls for Best Films and Best Television of 2020. Small Axe featured in ‘”The Best 50 Films of 2020”’ Introduction’ by Kevin Corless with small features in the section on ‘Mangrove’ at no 13 and ‘Lovers Rock’ which won the film poll. It was discussed by James Bell in the ‘” Television of the Year” Introduction’; in ‘The Year in Black Cinema’ by Nicholas Russell; and in reviews of the last three episodes in the film reviews section.

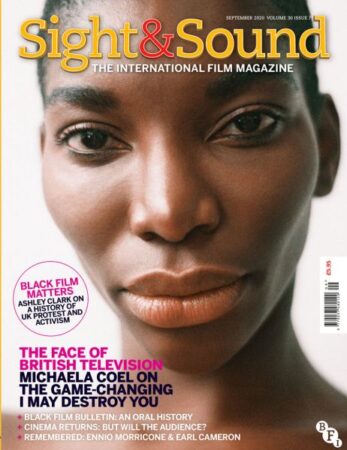

Then, finally, going beyond the time when Small Axe was being heavily promoted, we get Vol 31 issue 7, (September 2021) (fig 3). Nearly a year later, McQueen is one of four people put on the cover and he is interviewed again, this time for an issue that focuses on the future of film.

In exploring this extensive written material a bit more, a number of things are worth noting. One problem in talking about Small Axe is the question of what to call it or how to categorise it. Nearly all the writers in Sight & Sound over this period use the term ‘film’ or indeed ‘feature film’ for individual episodes and occasionally group them as an anthology series. No one uses the term mini-series for Small Axe which was the term later used by the Royal Television Society and BAFTA is relation to its appearance in their television awards.

‘Lovers Rock’ is picked out for exceptional attention by McQueen and others. In introducing the film poll, Richard Corliss points to the difficulties of categorisation but says that Lovers Rock ‘cries out to be experienced on a big screen, not least for the rapturous soundtrack to be blasted out as it should be’; in other words, it deserves to be treated as a film. James Bell, writing the introduction to the television poll, is more pragmatic. He says that Small Axe is ‘only not included in our [TV] poll because some of its five films had played in film festivals, and were conceived as standalone parts of a whole.’ It was therefore ‘eligible for our film poll instead’. The rules permitted or perhaps required ‘Mangrove’ and ‘Lovers Rock’ to be treated as cinema. They were eligible for the film poll and so naturally that was where they went.

In this examination of Sight and Sound’s treatment of the Small Axe project, it is striking how McQueen sets the tone of the discussion through his interviews and in particular how he uses the interviews to talk about the different categories of cinema and television. Firstly, there is the matter of what is not mentioned.[ii] In his interview with Olusoga, McQueen says that ‘these films should have been made 35 years ago, 25 years ago, but they weren’t and I suppose . . . I wanted to make as many films as I could to fix that’. Throughout all this publicity in Sight & Sound it is very rare to find anyone referencing what had gone before in terms of television: the work of Horace Ové; the black workshops making programmes for Channel 4 in the 1980s; the work of Menelik Shabaz; the careers of John Akomfrah and Isaac Julien or the more mainstream work of Gurinder Chadha and Nadine Marsh-Edwards.

What we do find in the interviews is McQueen’s rather fixed views about the storytelling possibilities of television drama. In a Sight & Sound interview in 2018 (Vol 28, issue 11, November) he was interviewed about re-making Widows (2018) as a feature film rather than a television series. This was before the magazine began reviewing the very dramas he criticised; the much-praised new television series from Netflix et al are described as ‘so rubbish’. They were overlong and narratively slack. In his 2021 interview, he similarly compared the narrative possibilities of cinema and television, to the latter’s detriment: ‘Story telling is a craft . . . It’s not about “I’ll tell you the rest next week”’. ‘Cinema’ he says, ‘having that limit to around a couple of hours to tell a story and hold an audience’s attention is valuable because it’s about craft’. When he praises television, it is for enabling him to get a wide audience who can learn something: ’it was about getting into the country’s bloodstream . . .I have never had a premiere like Small Axe on the BBC and Amazon, the response, the reaction and intergenerational responses it instigated, with people asking’ What’s going on?’ (2021). Television for McQueen tends towards the functional, cinema is for pleasure.

It is clear by 2021 that for McQueen Small Axe is indeed cinema. ‘I always made them for cinema’ he says. ‘The experience of watching something in the cinema is far superior to watching something at home. . . I love being in a cinema with an audience. I love the ‘oohs’ and the ‘ahhs’, the applause, the titters, the communal viewing’. [iii] Referring back to McQueen’s comment which gives me my title, I don’t know whether his mother watched Small Axe on television because in interviews McQueen focuses instead on the ecstatic response of his sister and his aunt to communal festival screenings of’ Mangrove’ and ‘Lovers Rock’.

Does it matter?

In its promotion of Small Axe, Sight and Sound, in its patrician way, predicted disapprovingly that, because of categorisation problems, ‘the hoary old ‘Film Vs TV’ debates will be rehashed past the point of tedium’ (Bell 102). I have taken the bait! But I do think that Sight & Sound’s promotion of McQueen’s work as film rather than television does have potentially serious consequences.

Firstly, it sets McQueen up as Exceptional. He is a Turner prize winner and an Oscar winner. He is positioned outside the history of British black filmmaking and outside Hollywood. The context for his work is himself, his earlier films, his art, his status as an auteur which give him clout. Could anyone else, particularly a young black filmmaker, really learn from his experience?

Secondly, and following on from that, Isolation. The collective work that went into this ten-year project is massively under referenced. McQueen is given credit for going as far as he possibly could to get a black crew. But it is significant that it was a panel put together by the RTS which really focused on collaboration (See https://rts.org.uk/video/production-focus-small-axe-rts-london and https://rts.org.uk/article/creation-steve-mcqueen-s-anthology-small-axe). It began by talking about how Small Axe was developed and held together while McQueen was doing other things. Producer Tracey Scoffield (fig 4), who had been brought in by McQueen and the BBC back in 2010, began her contribution by talking about another key contributor, researcher Helen Bart, who undertook the 126 interviews which were ‘read, listened to and filtered’ years before the Writers Room could be put together.

Thirdly, Functionalism. The Sight and Sound approach risks blocking off any attempt to review the five episodes of Small Axe collectively in terms of their aesthetic and thematic links or to treat them as something that can be discussed in the context of British television drama. McQueen’s tendency to see television as functional seems to affect some of the reviewers who assess episodes like ‘Education’ as indeed educational for the audience, filling in knowledge of a lost history. The aesthetic challenges aren’t described or discussed. Television can be political it would seem but it is not a place for formal experimentation. What if ‘Lovers Rock’ could be discussed as an astonishing piece of television within a connected series of historical dramas rather than a film manqué best seen at a film festival? Or ‘Education’ seen through the image of the boy who wants to be an astronaut?

Fourthly, Omission. There is very little reference in this discourse to the BBC which is given little credit for its funding and support. It had supported the project for over 10 years which is surely remarkable but McQueen doesn’t speak about it. This leaves many questions. How, for instance, did Small Axe come to be on BBC One? Corliss again explains this via exceptionalism, saying that that this is ‘is surely testament to the clout wielded by Steve McQueen’. But that doesn’t tell us anything. How was that first agreement made? Why did the BBC think it was worth it? Was Scoffield brought in precisely to handle foreseen complications? Why did the BBC keep faith over all these years while McQueen was off in Hollywood making other feature films? What oversight did it have? What could other filmmakers learn from this process and how did it work out for the BBC and for viewers? Recently, the BBC’s Director General cited Small Axe. He used it as evidence that the BBC had already been making programmes with a ‘distinctly British’ content. It would do more of this in order to counterbalance the ‘globalised’ drift of streamers like Amazon. What would Sight and Sound and international auteur Steve McQueen make of that? Would they support the BBC and Channel 4 in the fight for the continuation of some kind of public service broadcasting? Certainly McQueen, a beneficiary of BBC funding, has done nothing to indicate that he might contribute to that.

In thinking and writing about Small Axe, I always have in my mind the other poll, the one in which Small Axe did not compete: the television poll won by I May Destroy You, also a BBC production. Feminist Television Studies in the 1980s analysed the association between women and television in terms of its occupation of domestic space and the female-orientated nature of its most popular genres. I begin to think that this concept continues to have explanatory value when I contrast the refusal to treat Small Axe as television with the willingness of Michaela Coel, in 12 stunning 30-minute episodes, to take on the rhythms, flows and interruptions of episodic television and the generic diversity of its drama. In seizing the opportunity, Coel did indeed make something that deserved to be seen on the small screen. I should acknowledge that Sight and Sound put her on the cover (fig 5).

Christine Geraghty is Honorary Professorial Fellow at University of Glasgow. Her publications on television include a contribution to the 1981 BFI monograph on Coronation Street; Women and Soap Opera (Polity, 1991) and My Beautiful Laundrette (IB Tauris, 2004). Her BFI TV Classic on Bleak House was published in 2012 and she has continued to make a major contribution to Adaptation Studies. Most recently, she has published an essay on BAME casting in the 2010s in the journal, Adaptation . She is Book Reviews editor for Critical Studies in Television.

Footnotes

[i] I am grateful to Thomas Austin at Sussex University for organising the informative and stimulating symposium on Steve McQueen on 24th September 2021 at which I presented a longer version of this paper.

[ii] Thanks to Roy Stafford for drawing my attention to this. His detailed blogs on Small Axe can be found at can be found at https://itpworld.wordpress.com/2021/01/09/small-axe-an-introduction/ and are particularly valuable for providing a context for the period McQueen is evoking.

[iii] At a panel discussion of Small Axe at the National Film Theatre on 23rd October 2021, McQueen confirmed ‘these were feature films, I can say it now’ as if he had been constrained while making them and in the earlier publicity.