FOX’s horror-comedy series Scream Queens is the latest addition to the canon of Ryan Murphy and Co.’s anthology television series, alongside FX’s American Horror Story (2011-present), and the upcoming American Crime Story (2016). Scream Queens, named after the sobriquet for a female horror icon, is a hyper-stylised, retro-pastiche of horror and slasher cinema from the 1970s and 1980s. While contemporary television is no stranger to the horror genre, the long-forgotten slasher subgenre seems to have found a new home with FOX’s Scream Queens, MTV’s Scream (2015-present), and Chiller’s first original television series Slasher coming to the small screen next year. It’s been several decades since the slasher was in its heyday, and we’ve come a long way in terms of representation. One of slasher cinema’s most prominent detractors has been its problematic gender and sexual politics, particularly towards that of young girls and queer persons. How does a show like Scream Queens negotiate the problematic politics of its source texts in order to create a more progressive, contemporary slasher series? Well… the jury is undoubtedly still out on that one.

Scream Queens’ master narrative revolves around two things: The Kappa Kappa Tau sorority house, and Chanel Oberlin (Emma Roberts), the sorority’s popular, malicious president. The other girls bow down to her every whim, they’re even nicknamed Chanel #2, Chanel #3, etc. Her minions’ sycophantic slavery is reminiscent of the animalistic girl politics of the cult teen movie Mean Girls (2004), and the series in general is a commentary on the Darwinian social orderings of Generation Y – AKA millennials. Things are shaken up by a string of gruesome murders on campus, whereafter the series becomes a tried-and-tested whodunit mystery punctuated with wonderfully executed moments of comedic camp. The series is always poking fun at itself and this is one of the things it gets right; it never takes itself too seriously, allowing viewers to appreciate it for what it is: a meta-camp homage. However, a retro-pastiche of slasher cinema (which was never exactly well-respected in its time) needs to do more than follow the formulas of its antecedents in order to be successful in current times. Although Scream Queens does parody many of the stereotypical and reductive features of the texts from which it draws upon, it fails to ultimately transgress them and redefine the generic and ideological boundaries on which they are based.

As aforementioned, Scream Queens is an homage to that which came before it: slasher and horror films from earlier decades. Right from the get-go, there are endless references to classics such as Psycho (1960), The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), Halloween (1978), among others. Perhaps the most notable form of intertextuality is the presence of legendary scream queen Jamie Lee Curtis, who plays the university’s Dean, Cathy Munsch. Curtis rose to stardom after her involvement in slasher films such as Halloween and its various sequels and Prom Night (1980), and was known for her portrayals of the mousey, bookish virgin who eventually kills the hypermasculine psycho-killer. While some have read the figure of the “Final Girl” as a totem of female empowerment in largely conservative times, others have highlighted the overall representation of women within these films as sexist and misogynistic. Although Scream Queens does makes a point of accentuating these misrepresentations, it never manages to fully distance itself from its predecessors.

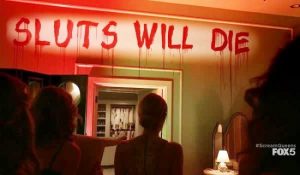

The series courts the idea of female empowerment and progressiveness, but routinely falls short. Take episode 2, “Hell Night”, for example. The new pledges’ cruel hazing ritual (in which Chanel #1 points out their physical flaws while they stand before her scantily clad) is interrupted by the presence of the “Red Devil” killer in the sorority house. The girls band together, donning whatever weapons they can find lying about the house. Naked, humiliated, and powerful. The girls are a pluralistic pantheon of different kinds of girlhoods, sexualities, interests, cultures, and body types. In this moment, however, they share a collective feminine agency in attempting to disrupt the machinations of the (presumed) male psycho-killer. Regrettably, this transgression of gender roles and subversion of pre-established notions of “girlhood” in the horror genre is short lived. After this brief moment of quasi-empowerment, the girls are confronted with one of the most pervasive and poorly understood motifs in the entirety of the slasher film: sexual behaviour, of any kind, results in death. The Red Devil has inscribed “Sluts Will Die” on the wall of Chanel’s bedroom. By satirising (but not subverting) one of the slasher’s most infamous tropes, the series dangers on being just as regressive as its analogues from earlier decades.

Another particularly problematic character comes in the form of Nick Jonas’ Boone, who fills the gay quotient of the series. Considering Scream Queens is a contemporary campy slasher series from the minds who brought us Glee (2009-2015), I imagined the LGBTQ representation would be plentiful and, broadly, progressive. Again, the slasher film was in its prime when socio-cultural constructions of homosexuality were largely phobic and detrimental. Before the series aired, Nick Jonas stated that he was proud to play a strong, progressive gay character on television. While Jonas’ early report on his character would suggest that Scream Queens portrays homosexuality as normative and unproblematic, Boone is cast as the gay villain – a common trope from the horror genus which would have been better left in the past. Instead of politicising him, Boone’s gayness works to depoliticise and Other him, with the majority of the characters viewing Boone, and his homosexuality, as strange and unsavoury. This is further problematised by the 9th episode of the series, “Ghost Stories”, in which we find out that Boone was only pretending to be gay all along. On one hand, this is problematic as it suggests that homosexuality is entirely performative and can be mimicked for illicit purposes. On the other, Murphy and co. may be attempting to highlight the stereotypical representation of gayness within horror texts by having a straight actor/character perform gay masculinity in ways in which hetero-normative audiences/characters are accustomed to. Either way, this is one of the most prominent examples of political pastiche within the series and it ultimately lacks discursive conviction and is narratively ill-executed.

Overall, Scream Queens doesn’t grasp at its potential for positive portrayals of previously marginalised characters in horror cinema. It flirts with the idea of being transgressive and, on rare occasion, delivers moments that are suffused with political heft and teeter on the cusp of subversion. More often than not, however, the show acts as a reminder of the regressive sexual and gender politics from decades before. The series has given itself plenty of opportunities to push beyond the regressive ideological boundaries which it is built upon, but falls short in favour of parody or camp. Some of this works better than others; for example, the girls’ arguable and intermittent empowerment and the casting of Jamie Lee Curtis as a no-nonsense authority figure generally work effectually with the parodic elements. However, Boone’s problematic representation as a heterosexual performing as a homosexual for the sake of a villainous revenge plot works to destabilise these potentially progressive and politicised depictions. Alas, the majority of Scream Queens’ narrative serves as a modern day update on the problematic slasher film, with not-so-modern day representational politics in tow. Here’s hoping that the next iteration of the series, rumoured to be Scream Queens: Summer Camp, fares better than the first.

Jordan Phillips is a postgraduate researcher and teaching associate at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, whose current research explores issues of queerness in the horror genre. The main focus of the research is to determine why queer audiences find pleasure in negotiating queer meaning in a predominantly heterosexist genre of films.