In his 1990 autobiography, Days of Vision (London: Methuen) the late television director and writer, Don Taylor, rhetorically asked what the television studio could offer that film, by then the established mode for drama production, could not. He gave the following heartfelt and poetic answer:

‘…an empty space. A prepared canvas ready to paint on; the vacuum of an open mind waiting to be filled. It can offer the landscape of the imagination, ready to be entered, a world inside the head as vivid, often more vivid than the world outside the eyes that the film camera photographs so faithfully. It can offer nothingness, waiting to become something, a world waiting to be created out of the chaos of four characterless walls, a shiny floor, and a grid of lights. It is something waiting to happen, a statement ready to be made. One object or person placed within it makes a quite specific and individual point. Two, and the play begins.’

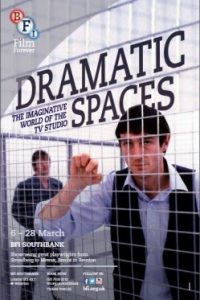

Taylor’s conception of the studio as an exciting space of creative potential, perfectly encapsulates the inspiration behind the ‘Spaces of Television’ project’s forthcoming season at BFI Southbank, ‘Dramatic Spaces: The Imaginative World of the Television Studio’ running throughout February 2014. The season (curated by myself and Dr. Billy Smart of Royal Holloway, University of London) revisits the exciting 20 year period between 1964 and 1984, when developing television technology, associated with the ingenuity of certain producers and directors, revolutionised what could be achieved in the studio. Our programme showcases a selection of productions – some unseen for nearly 50 years – that highlight the breadth of vision in the use of studio space and the creation of a new form specific to TV drama.

The line-up, which includes both naturalistic and overtly stylised single plays, is intended to explore several dramatic and aesthetic tropes within ‘Golden Age’ studio production, and to demonstrate what is remarkable and unique about this mode. Taylor, the studio’s staunchest advocate, noted that studio drama is ‘always the exploitation of a dramatic convention… the particular compromise it makes with naturalism is far less complete’ (1990: 258). Too often dismissed as ‘stagey’ or ‘theatrical’ (often by advocates of the then-emergent Loachian filmic realism), the advantages of the studio’s non-naturalism – its capacity for rich and varied styles of visual aesthetics, performance, and dialogue – deserve to be celebrated.

The intimate, carefully constructed studio space was ideally suited to tell intense, claustrophobic narratives, such as Don Taylor’s horrifying The Exorcism (Dead of Night, 1972) and Alan Bridges’ version of Strindberg’s Miss Julie (Theatre 625, 1965). At the same time, the vast resources and sprawling spaces available provided a blank canvas for the realisation of productions such as Brecht’s epic The Life of Galileo (Festival, 1964) and Howard Brenton’s Desert of Lies (Play for Today,1984), in which the studio was transformed into the Kalahari desert.

Other plays exploited the minimalist studio space, and adopted more self-consciously stripped-down aesthetics such as the stark white palette of Alan Clarke’s harrowing depiction of psychological warfare, Psy-Warriors (Play for Today, 1981), (more below) and the black cyclorama of The Saliva Milkshake (Centre Play, 1975), which intensified its evocative use of monologue.

The advent of blue-screen image compositing, known by the BBC as Colour Separation Overlay (CSO), opened up new possibilities of spatial representation by allowing live action to be superimposed on to any background. Our season features three striking examples of CSO, and offers a rare opportunity to see an all-CSO version of Caryl Churchill’s The After-Dinner Joke (Play For Today, 1978); Philip Saville’s highly experimental The Journal of Bridget Hitler (Playhouse, 1981) which combined different genres including drama, historical reconstruction and studio discussion; and Howard Schuman’s never-transmitted Censored Scenes From King Kong (1973).

I now want to expand briefly on four prominent characteristics of studio plays in the season: intimacy, confinement, minimalism, and videographic effects. Although I mention only a few plays here (being careful not to reveal too much of their plots), more in-depth blog posts about each production will be available on the Spaces of Television blog, nearer the time of the screenings.

Intimacy

The season opens with a striking example of Don Taylor’s mastery of close studio form, his ‘socialist ghost story’, The Exorcism, a chilling tale of two middle-class couples who become subject to a supernatural presence in a recently renovated 18th Century farmhouse. The terror of the haunting was achieved through Taylor’s skillful treatment of the characters within the confined studio interiors, which exploited the intimate visual language of the studio.

As the play progresses, much of its horror works through the power of the human face, via tight shots focusing us on the protagonists’ frightened reactions. In the opening scenes, wider shots are used to situate the characters within the space and alert us to the narrative significance of the house; hosts Edmund (Edward Petherbridge) and Rachel (Anna Cropper), show off their beautifully restored old property to friends, Dan (Clive Swift) and Margaret (Sylvia Kay), both couples admiringly gazing at, touching, and interacting with the rooms and fixtures.

As strange things start to happen, a growing sense of menace is generated through atmospheric lighting (after the electricity and phone line are lost), haunting music, and increasingly intense, scrutinising close ups of the protagonists faces. Rachel is recurrently framed looking slightly upwards and into space, as if gripped by the atmosphere of the room.

The system of looks and reactions established between the characters via the multi-camera set-up (live vision mixing between cameras) heightens the mounting horror. For example, during an unnerving party game (in which Dan suggests to his blindfolded wife that the ice cube he holds in front of her is a cut throat razor), a sudden split-second cutaway shot of Rachel’s reaction in the other room makes the scene even more frightening.

The production is a testament to the power of close visual language, and the frisson of continuous performance recorded as live, both qualities engendered by the studio mode.

Confinement

The confined space of the studio was often used in the signification of characters’ entrapment, as demonstrated in a double-bill of plays directed by the late Alan Bridges (who, sadly, died in December 2013). Strindberg’s Miss Julie and David Mercer’s Let’s Murder Vivaldi are both potent tales of sexual conflict, jealousy and destructive power dynamics, played out through and within the studio space.

In Let’s Murder Vivaldi, young modern couple Julie (Glenda Jackson) and Ben (David Sumner) and jaded middle-aged spouses Gerald (Denholm Elliott) and Monica (Gwen Watford) demonstrate different forms of aggression within their equally troubled and violent relationships and Julie and Gerald embark on a misjudged and unsuccessful affair.

Describing the play as ‘a radical reclaiming of television drama as a site of structured dialogue, inner exploration, psychological encounter, and close-knit social situation’, McMurraugh-Kavanagh and Lacey (‘Who Framed Theatre? The “Moment of Change” in British TV Drama’, New Theatre Quarterly, 15:1, 1999, p.71) argue that it directly foregrounds its own construction, through its carefully scripted words and consciously ‘theatrical’ frontal shots of rooms. The Financial Times television critic, T.C. Worsley, wrote: ‘This is an artificial comedy written with an ironic elegance line by line […] Shapeliness and wit […] can be used, as they are here, for sharpening the knife of the theme’. (Television: The Ephemeral Art , London: Alan Ross, 1970, p 71) ‘Sharpening the knife of the theme’ is a particularly appropriate turn of phrase in this instance, as knives feature prominently in the play, and are used by more than one character against another.

The clinical, composed near-symmetrical mise-en-scene in shots of Gerald and Monica in their home works in tandem with the scripted language, the artificial treatment spatially echoing the barbed formality of their choreographed exchanges.

Alan Bridges’ coolly controlled framing of the characters in their spaces eloquently conveys their distance from each other. Characters are frequently positioned at the edges of rooms with a conspicuous gulf between them – suggesting their emotional distance, or, when alone, emphasizing their alienation, as during Gerald’s and Julie’s awkward liaison in a hotel room.

The edges of rooms are often visible, further representing characters’ entrapment by delineating on screen the parameters of the spaces. The simple, yet bold, formal approach exacerbates the play’s ironies and uses the studio’s ‘compromise’ with naturalism to maximum effect.

Minimalism

Another example of the overt framing of ‘entrapped’ characters in the studio can be seen in Psy-Warriors, David Leland’s 1981 Play For Today directed by Alan Clarke, confinement, in this case, literal and political rather than metaphorical and personal. The play concerns the plight of three terrorist suspects, detained in a military installation under suspicion of committing an IRA bomb attack, and depicts the various brutal psychological and physical interrogation methods used upon them.

Describing the play as Clarke’s ‘most stunning piece of studio direction’, Dave Rolinson outlines how the act of ‘looking’ is foregrounded through different strategies including ‘the use of long-shot compositions from side-on, the querying of space through close-ups shot on long lenses [and] a mediating foregrounding of the bars of the cages…’ (Alan Clarke, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005: 122).

These insistently stylised aesthetic strategies also demonstrate Clarke’s confident, stripped-back, minimalist approach to studio aesthetics, using a predominantly white palette with austere geometrical grid lines of the cages emphasising their occupants’ confinement. Exploiting the enclosed studio space, these devices give the play further force as a meditation on the structure of the British state and institutionalised brutality.

Videographic environments

Withheld from the schedules ostensibly because of its unusually offbeat, camp sensibility (censorship only coincidentally a theme of the play), Howard Schuman’s Censored Scenes From King Kong depicts a young journalist, Stephen (Michael Feast) who, after waking from a three year coma, investigates the suspected suppression of a scene in which the gorilla has sex with Fay Wray.

Alongside more conventional studio sets (TC1 transformed into a warehouse and a cabaret club), CSO pop-art style collages are used to represent the different spaces where Stephen pursues the missing footage: the office of a film professor; ‘Kongomania’ a private museum of film memorabilia; and the hotel room of the film’s Assistant Special Effects man. Although the decision to use CSO in the play was influenced by budgetary considerations (being cheaper than producing three sets) the multi-media collages offer an appropriate and vibrant means of enlivening certain themes, including Stephen’s post-1960s cultural disorientation and 1930s Hollywood film representations.

Across these, and many other television plays, featuring a myriad of exciting stylistic devices, the season shows that studio drama really did produce ‘the landscape of the imagination’ within its walls.

Dr Leah Panos is a Post-Doctoral Researcher on the Spaces of Television project based at the University of Reading. Recent case studies for the project include work on the use of the Steadicam in Brookside, the television plays of Howard Schuman, aesthetics in the TV studio musical Rock Follies, and the role of the designer in 1970s dramas using Colour Separation Overlay.