Why the parentheses? Well, the established argument is that television’s very domesticity and ‘ordinariness’ militates against any capacity to produce ‘stars’ in the sense that cinema is traditionally perceived to have done. This conception hinges on the performer in question being both ‘knowable’ (via their famous screen roles) and somehow out of reach, and it is notable that the majority of performers initially selected for study were, if not already deceased, either retired or in the twilight of their careers (e.g. Monroe, Garland, Garbo, Wayne), and produced their best-known work in Hollywood. Even today (and possibly against our better judgement), Tinsel Town retains an air of glamour that domestic programming cannot hope to replicate, perhaps more so here in Britain due to our geographical remove. There is no chance now of us ever glimpsing the classical Hollywood star in an everyday scenario; to paraphrase an old Steve Martin line: not only are most of them dead, they are thousands of miles away. If unattainability is the key to possessing any kind of stellar aura, those working in the humdrum, everyday medium of television are, by dint of the pervasiveness which makes them household names, unable to match their cinematic peers for star impact; they are simply too accessible and familiar. Rock musicians can perhaps make some claim to stardom – but TV actors? These are ‘personalities’ at best.

I’ve always had difficulty with this argument, perhaps because – unlike the majority of those who proposed it – I grew up with television, rather than cinema. My introduction to the Hollywood stars of yesteryear therefore came via screenings on television; a magical box which held little distinction (for me) between John Wayne and John Thaw, each of whom had an equally vivid screen persona. Television was part of my daily routine, yes, but it was simultaneously a separate, special world. The ‘ordinariness’ and ‘availability’ typically accorded to television performers in star studies would not have resonated with me then, and to an extent it still does not today; TV was just as exclusive a domain to me as Hollywood might have been to those raised in 1950s Britain. I grew up in the village of Tiptree, an Essex backwater whose only impact on the outside world was via its jam produce (which can still be purchased as far afield as Paris and Rome).[1] There were few local personalities, let alone stars; BBC Essex DJ Timbo once opened a school fete, and as a cub scout I was taken to see a production of Mother Goose at the Colchester Mercury which featured one of the actresses from Angels (BBC, 1975-83). However, in my formative years this was as close as I came to connecting with the (to me) glittering world of television.

In the years since my departure, Tiptree has been visited by no less a production than Midsomer Murders (ITV, 1997- ), filming (perhaps inevitably) at the Jam Factory. Such an invasion from TV land would have been an event on which my teenage self might have dined out for months. As it was, until my adult years I felt as though television and its denizens occupied some alternate dimension – regardless of the fact that I could summon their image at will with the twist of a Ferguson dial. I cared far less for cinema (a very occasional treat), and besides, it seemed just as unlikely that I would bump into Mark Hamill outside Budgens as I would Tony Hart.[2]

Tiptree’s principal claim to fame (other brands of fruit spread are available)

The one exception to this ingrained sense of exclusion came during a family holiday in Yorkshire. Our first stop was the village of Askrigg; until a few years previously, home to All Creatures Great and Small(BBC, 1978-1990). As we drove in, I couldn’t help noticing a large van, bearing the Corporation logo, parked on the other side of the road. Though I hardly dared make the obvious connection, my heart still skipped a beat; could it possibly be…?

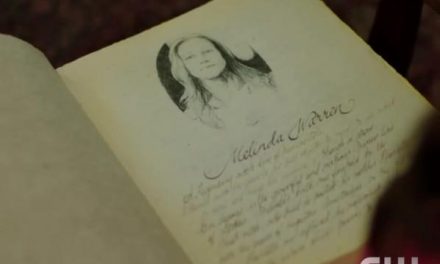

An elderly, flat-capped local quickly confirmed that the screen veterinarians were indeed making a return: ‘Aye. They’ve got that Peter Davidson up there.’ Pausing briefly to thank him (there was no time to correct his mispronunciation of the surname), I ran up to the hostelry where Mr Davison stood, in full Tristan costume, chatting to a group of American tourists about the merits of Yorkshire Ale. I nervously enquired whether it would be possible to take his photograph, and was about to press the shutter release when a BBC script girl asked if I would prefer to have my photograph taken with Peter? Needing no second bidding, I lined up next to the great man for an historic portrait.[3]

The deed done, I thanked Mr Davison and retrieved my camera. The moment was complete; nothing now could spoil it. My mother bustled forward, effusive in her gratitude: ‘Thank you so much; you’re all over his bedroom wall at home!’

Objectively speaking, it is not possible to say which of us was more discomfited by this statement, but I’m fairly certain it was me.

The intensity of my teenage reaction to this first encounter with the world of television can in part be accounted for by the fact that I was an avid watcher of Doctor Who, from which Mr Davison had only retired the previous year. I was admittedly slightly less excited – though still somewhat awed – by the presences of Christopher Timothy, Robert Hardy and Carol Drinkwater, and opted not to ask for their autographs, instead living vicariously as my less inhibited younger brother did brisk business indeed.

These sentiments of course date back to childhood and adolescence, and do not constitute a particularly robust rebuttal of the old film star/TV personality argument. No matter how otherworldly these television performers may have seemed in my (admittedly provincial) youth, I am no longer a gawky 14-year-old. Were I to meet Peter Davison today, as a gawky forty-something, my sense of awe would doubtless be significantly lessened, to the extent that I would probably be able to smooth over the whole misunderstanding about those posters on my bedroom wall (many of which have now been taken down).

However, I still do not subscribe to the proposition that television, by its very nature, is incapable of producing ‘stars’. I fail to see why a performer need be resident in Beverly Hills (or deceased) to possess an aura of exclusivity. Admittedly, the early focus on Hollywood has now lessened, with work on British stars and stardom since conducted by Geoffrey McNab and Bruce Babington. James Bennett has opened up the discussion of TV stardom, questioning the concept of TV fame being in some way inferior via his examination of the televisually and vocationally skilled, examining comedy performers Benny Hill and Ricky Gervais alongside presenters such as Alan Titchmarsh and Cilla Black. However, the focus tends to remain on non-actors, or those who specialise in comic roles; television thesps generally remain relegated to some form of second rank in terms of academic analysis. Given the proliferation of chat shows and Twitter feeds by which the public now have access to Hollywood’s finest (?), the latter are arguably as constant a presence in our lives as their small screen counterparts; distinctions have become blurred in ways that were neither possible nor desirable in Hollywood’s Golden Age, when performers like Cary Grant deliberately avoided television work in order to maintain their star aura.[4]

What has any of this to do with Muswell Hill? Well, for many years now I have lived, on and off, in this pleasant, leafy suburb of north London; a locale steeped in television and film history. The main incentive for renting my first bedsit was that the window held a view of Alexandra Palace, birthplace of BBC television, and silent movie buffs might be aware that director Robert W. Paul built Britain’s first film studio here in 1898.

Muswell Hill, N10; a living history in visual media

Home to many a well-known TV actor, Muswell Hill proved to be the obverse of Tiptree; from the position of an outsider looking in, I suddenly found myself rubbing shoulders with the great and good of television drama and sitcom. A few days after my arrival I spotted Tessa Peake-Jones, then best-known for playing Raquel in Only Fools and Horses (BBC, 1981-2003), outside Sainsburys, and the cast list quickly grew. John Savident, then riding high as Fred Elliott in Coronation Street (ITV, 1960- ), could often be seen walking his dog in Highgate Wood, while the late John Ringham, Penny’s put-upon father Norman in Just Good Friends (BBC, 1983-86), was also a familiar face on the Broadway. During the heyday of Spaced (Channel 4, 1999-2001) I spotted Tim (Simon Pegg) and Mike (Nick Frost) buying tickets at Highgate tube, while Brookside’s (Channel 4, 1982-2003) Bel (Lesley Nightingale) and Georgia Simpson (Helen Grace) were both living in the area at the time of the infamous incest storyline. Such high visibility would seem to support the old ‘personality’ argument; we, the audience, recognise and feel that we know these performers purely because we identify them (as I have just done) with the parts they play. This is presumably what prompted judges in the recent trials of Michael Le Vell and William Roache to instruct jury members as to the distinction between the actors and their TV roles. However, their ready availability also makes them far more ‘spottable’ than a Hollywood legend could ever be (‘You’ll never guess who I saw in Marks the other day…’); indeed, it is possible to perceive a tacit acknowledgement of this on the part of the performer. Upon realising that they have been recognised while going about their daily business, the actor in question will either drop their eyes immediately to discourage any attempt at contact (I’ll name no names), or respond with an avuncular nod, as if to say: ‘You’ve seen me, and I’ve seen that you’ve seen me. You think you know me, though I know that you don’t – not really – but that’s fine. It all comes with the job.’

So much for attainability, but doesn’t the very fact that the performer, when viewed out of context in this way, inspires in the spectator such a shock of recognition – a small but tangible thrill at having spotted ‘him/her off the telly’ – also indicate that they possess an aura of sorts? Nothing as monumental as the star figures generated by Brad or Angelina, who I admit I’m not likely to see chatting to Alison Steadman outside the grocer’s, or struggling to push their pram into W.H. Smith like John Simm – but an aura nonetheless; something that gives the spectator pause, and holds (most of) us back from actually walking over and vocally hailing said actor as a fellow well met.

The quality I’m struggling to pinpoint here is one particular to television actors. I don’t challenge the validity of the ‘personality’ argument with regard to presenters, newsreaders and non-performing ‘celebrities’; these are equally visible in a metropolis like London (for instance, Boris Johnson forcing his press entourage through the BFI Southbank entrance as I attempted to make my exit), yet the frisson of recognition is not of the same order. These people I simply recognise, and move on. Television actors, however, hold a certain fascination. This may be an entirely subjective reaction – possibly born of my professional interest in the relation between actor and character, and a desire to unpack the two – but it’s there, nonetheless.

I should add that I am no longer of an age where my autograph book will automatically appear at the sight of a famous television face. I have interviewed several actors as part of my research into small screen performance, and would not have been doing my job properly had I become over-awed by associations with their more familiar television personae; put simply, it is possible (and necessary) to separate the person from the part. The untimely death of Roger Lloyd Pack last month reminded me less of his performance as Trigger (under which name a large number of tabloids inevitably reported his passing) than the personable gentleman who was immersed in bread-making when we met at his home, or the interest he expressed in my digital voice recorder (he used one of his own to record accents and dialects when researching characters, and we ended up comparing devices). Television actors are, after all, people – but then so were the Hollywood greats of yesteryear, who have been elevated to a higher (heavenly?) sphere for academic study. The effect these US stars produced in audiences may have been of a greater magnitude than that generated by their television equivalents, but this does not automatically negate the possibility of the latter possessing a different kind of aura, specific to their medium, no matter how ‘reachable’ they may seem in comparison. This distinction is perhaps one of personal perspective, and it could be as simple as a generational difference; television and its performers clearly hold a greater significance for me than for film studies colleagues, or those who did not grow up with TV as their primary medium of entertainment. As already stated, I can understand the appellation of ‘personality’ to certain types of television performer, occupying as they do an arena separate from an actor in a cinematic narrative. It is true that the television names cited herein lack the international fame and cultural import of Hollywood’s golden greats; film and television are distinct media, and so do perhaps require distinct terminology. Yet to group any and all who appear on television under one term seems needlessly limiting, its lack of nuance failing to take into account the particular qualities of – and effects generated by – acting for television as opposed to film. This piece is an attempt to articulate what I perceive as the need to more fully consider the possibility of the television actor as star – or at least as something beyond a ‘personality’.

Why the parentheses? I’m not entirely sure.

Dr Richard Hewett teaches television and film at Royal Holloway, the University of London. He has contributed to The Journal of British Cinema and Television and The Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, and lives in Muswell Hill.

[1] The local Anchor Press was also responsible for printing Target’s Doctor Who novelisations, but they ceased operations in the late 1980s – and I had anyway to travel to Colchester in order to actually purchase the books.

[2] Darth Vader did once visit Chelmsford shopping centre, but even then I suspected that it was an anonymous, costumed hireling, rather than Dave Prowse himself.

[3] I still have that photograph, which I am not going to reproduce here. Mr Davison hasn’t aged as well as me.

[4] Aside of events such as his 1970 Oscar acceptance speech, Grant’s only TV appearances were an uncredited role as a hobo on the Dave and Charley show (NBC, 1952), and a wordless appearance as an audience member on The Jack Paar Show (NBC, 1957-62). Paar opted to interview the man sitting in front of Grant, deliberately ignoring the star as an in-joke.