I have been writing about Samuel Beckett’s film and television plays for over 20 years, but until recently I had not studied screen adaptations of his theatre plays. A new collection of essays about adaptations of Beckett’s work after his death in 1989 gave me an opportunity to write about the Beckett on Film project (2001) that adapted all 19 of his theatre plays. The project was prompted by a season of performances at the Gate Theatre (Dublin) in 1991. The adaptations, directed by many different international auteurs and featuring star actors, were screened at film festivals and on television, then sold as a DVD box set and uploaded as online video; over the years the project was modified to fit new media conditions. I had to think more deeply about adaptation, medium-specificity and convergence. This blog is the short version of a longer story of working through those issues.

From stage to screen

What holds all 19 plays in Beckett on Film together is Beckett’s name. The very title indicates this, and the entire text of each of his plays is delivered uncut. Completeness and fidelity were the conditions the project’s producers had to satisfy to get copyright permission to adapt the plays. Property rights provide some stability across porous media boundaries, which I think is an important factor to bear in mind about adaptations of all kinds.

Adaptation enabled Beckett’s plays to shift from live performance to the screen but might separate them from their origins as theatre. Because of its associations with transformation, adaptation implicitly questions textual identity and stability. The signalling of theatricality in some of the Beckett on Film adaptations, such as in Catastrophe (directed by David Mamet), can be seen as a recuperative strategy to address this. It was shot on location in the dilapidated Wilton’s Music Hall in London, invoking a theatricality in ruins, and features the stage actors John Gielgud and Harold Pinter (also a playwright). Some of the screen adaptations proclaim that they are not theatre, while foregrounding it at the same time.

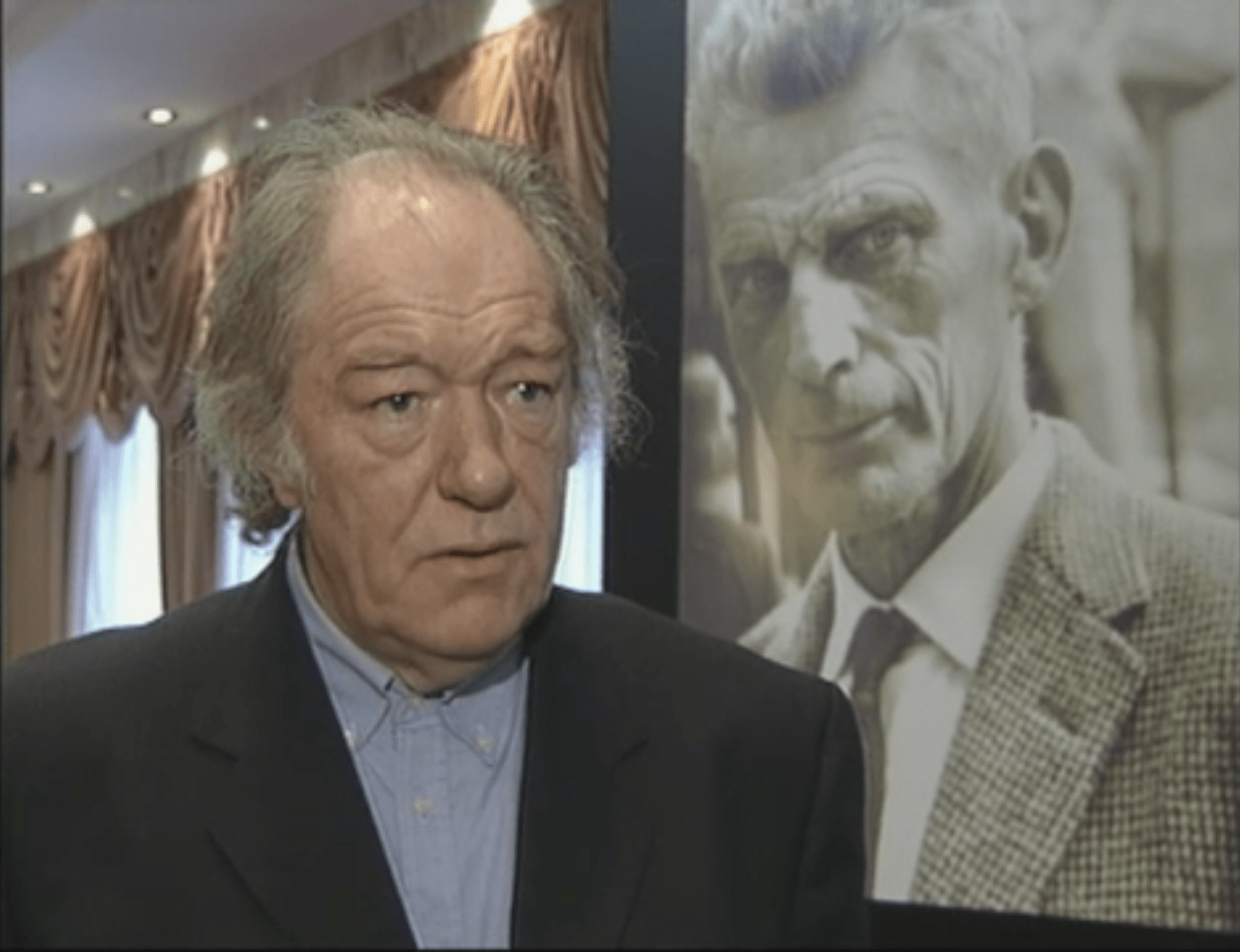

The Beckett on Film adaptations were first screened at film festivals in New York, Toronto and Venice, but the official launch was in Dublin in February 2001, and emphasised Beckett’s Irishness and literary eminence. The launch was covered on Irish TV, on RTÉ news, and featured speeches by the channel’s Director General and an interview with the theatre actor Michael Gambon (Fig. 1, who starred in the adaptation of Endgame). Beckett on Film was positioned on TV as both cinema and theatre, oriented around Beckett the Irish playwright but also around the films’ famous directors (Karel Reisz, Atom Egoyan, Neil Jordan, Anthony Minghella…). Beckett’s authorship and his estate’s authorisation of the adaptations provided discourses of coherence and value, despite the films’ diverse visual styles, as the face of Beckett looming over Gambon suggests in Fig. 1.

The adaptations were co-produced by Tyrone Productions, which had previously made the video of the stage show Riverdance, TV entertainment specials (like Christmas Carols with The Priests) and programmes in the Irish language. Like these, Beckett on Film was positioned as expressing Irish identity. The other production partners included the Irish Film Board, supporting and promoting Irish film and television, Culture Ireland, and the UK’s Channel 4 TV, which supports independent films and cultural diversity. The production company Blue Angel owns the films’ subsidiary rights (TV broadcast, DVD sales, streaming and merchandising), and negotiated TV screenings on RTÉ, Channel 4 and PBS (USA). The project had many links to cinema auteurs, its title incorporated the word Film, some of the adaptations referenced cinema history and technology (like Enda Hughes’ Act Without Words II, Fig. 2) and it toured the international film festival circuit, but financially the project was underpinned by television investors. Beckett on Film straddled different mediums, finding a place in each one.

Screening, distribution and resilience

Channel 4 had bulging coffers, thanks to profits that had risen from £330 million in 1993 to £650 million (Born, 2003) by the time of Beckett on Film. According to Michael Jackson, the channel’s Chief Executive, Beckett on Film was ‘not commissioned with profit in mind’ and was a ‘classic example of cross subsidy’ in which income from commercially successful output was used to fund programmes with perceived public value. This was recognised when the project was awarded the South Bank Show prize for Best Television Drama in 2002. When screened on RTÉ and Channel 4 television in 2001 the plays achieved low ratings but they fitted the Public Service Broadcasting remit of the channels.

There was an economic downturn around the millennium that reduced advertising income, and at the same time digital multichannel television and beginnings of internet TV fragmented television audiences. The Beckett adaptations got rather lost in Channel 4’s schedules and in Ireland, ‘many [viewers] taped them, because they were worthy and should be archived, but never got around to watching them.’ (Sheehan, 2004) But Channel 4 found a new way to use the programmes and moved Beckett on Film to a daytime slot under its 4Learning brand, targeting schools and colleges. The two major providers of curriculum support on television, the BBC and ITV, had withdrawn from educational broadcasting on their main channels in 2004, moving such content to specialist channels or online. Channel 4 stepped in, offering educational material in a distinctive way. Beckett on Film slotted into a strategy to develop programming niches that others had abandoned, and to address specific audiences that were under-served. Beckett on Film adapted again, fitting into an audio-visual ecosystem that was continually in flux.

Then Beckett on Film was released as a DVD box set (Fig. 3), price £100, via the Channel 4 website. In the early 2000s Channel 4 was pioneering multi-platform and interactive television in which programme brands encouraged audiences to migrate from television to DVD, to the internet and back. The channel also needed to monetise programme-related products, to generate income. Beckett’s plays were carried along in a larger shift of educational and high-cultural resources from analogue, time-bound mediums towards digital products to be owned and consumed at the user’s convenience. The DVD package aligns with cinephilia’s box set culture, which Barbara Klinger (2008) calls ‘a mainstreaming of the educational imperative’ and ‘a signifier of erudite taste’. The box set incorporates a 40-page collectors’ ‘souvenir book’, for example.

YouTube now hosts free, unofficial uploads of many of the Beckett on Film adaptations, where users can evade the relatively prescriptive explanatory discourses offered by the DVD’s extra features. Viewers commented on the Waiting for Godot adaptation (directed by Michael Lyndsay-Hogg, uploaded in 2018), for example, noting its emotional impact, its usefulness for university students, and that it is a boring waste of time. YouTube makes these relationships between users and the film public, surrounding the adaptation with an expanding context of users’ comments. Like DVD, online video is a kind of curation and archiving of the Beckett on Film project, more democratic but more disordered than DVD. When we look at how adaptations carve out a path through different audio-visual mediums, we can see how the mediums jostle amongst each other, converging and diverging in new ways, in complex processes of interaction and appropriation. By adapting to changed opportunities and constraints, both a medium and the text it adapts can suit themselves to the demands of the moment. It’s a jungle out there, and adaptation is a strategy that texts like Beckett’s use in order to survive.

Jonathan Bignell is Professor of Television and Film at the University of Reading. He works on histories of television drama, cinema and children’s media. Some of his work is available free online from his university web page or from his academia.edu page. This blog was prompted by his work on the book Beckett’s Afterlives: Adaptation, Remediation, Appropriation (2023), which he co-edited with Pim Verhulst and Anna McMullan, and in which Jonathan has a chapter about the Beckett on Film project. Jonathan is grateful to Michael Jackson, former Chief Executive of Channel 4, for telling him about the channel’s role in the project.