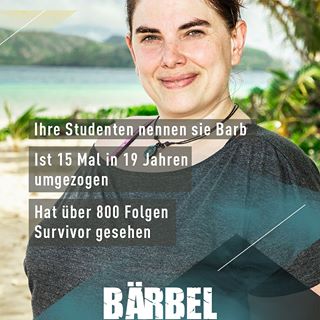

Factual television, as an academic area of interest, has become quite vogue. Not content, merely to look on from afar and research a variety of factual TV programming, some academics have decided to take part in some of the said programmes. For instance, British audiences have recently been exposed to the often chaotic and eccentric behaviour of Professor Tim Wilson on Channel 4’s The Circle, whilst German audiences (and social media) have been treated to the survival instincts of our very own Dr Bärbel Goebel Stolz (Coventry University) on the German version of Survivor.

https://twitter.com/C4TheCircle/status/1176745900594651137

My own contribution to this area has not been so bold, but nevertheless, it has been an attempt to draw attention to what has become, for me, a fascinating area of teaching and learning in television studies.

Last year i was given the opportunity to research, write, and deliver content and lectures for a new module on 21st Century factual Television for the University of Salford. It was an area of television studies I had long wanted to explore and teach, simply because in my conversations with students I noticed they watched a lot of TV (Mainly Reality and Makeover TV) that fell under the factual TV category.

Two Premises

The module is built around two fundamental premises. The first being that Factual TV programming forms a substantial part of TV schedules, and therefore its popularity, both with producers and audiences, is an aspect of the television experience worth studying. In fact, the popularity of factual TV forms has not gone unnoticed by streaming giant Netflix who have increasingly added all manner of factual TV programmes to their curated library of content. The second premise is that factual TV has had to develop and change to meet the commercial and cultural demands of a competitive, multi-channel, global TV landscape, and therefore these developments and changes are worth examining as part of an overall examination of change in television. The module essentially asks students to identify and examine the nature of these developments and changes in factual TV programming. As Annette Hill observes in her wide-ranging study Restyling factual TV: audiences and news, documentary and reality genres (2007), contemporary Factual TV ‘describes a ‘topsy turvey world…It is a space where familiar factual genres such as news, or documentary, take on properties common to other genres.’ (p.1). For Hill, factual TV genres have had to incorporate ‘entertainment values’ in order to compete in a competitive TV landscape and so traditional factual TV genres, such as Current Affairs, Science and History TV programming, and others have made a whole range of changes, from the people presenting these programmes, to the use of new technology, and especially to the type of content these programmes now include.

Various kinds of history, science, current affairs, documentary and other popular factual genres have undergone change and are part of a momentous time in broadcasting. Some genres, such as Reality TV and Makeover TV, are actual products of these changing turbulent times in broadcasting in the TVIII/TVIV era. When we talk about contemporary factual TV, we need to talk about genre and how distinctions between genre categories have recently become blurred. Hybridity is now the distinctive feature of factual TV.

Areas of Study

Bärbel Goebel Stolz on the German (2019) version of Survivor. The caption reads: “Her students call her ‘Barb’. Has moved flats 15 times in 19 years. Has watched more than 800 episodes of Survivor.”

But which factual TV genres and forms are significant to a study of the developments and changes in 21st Century Factual TV? We can take it as read that Reality TV has to be included, not just because students watch a lot of Reality TV, but also because so many respected academics have written on the subject (and even taken part). In fact, the genre is vast and could quite easily have formed a dedicated module (if not a Degree) all by itself.

The 21st Century Factual TV module examines a wide range of factual TV genres and forms, from Wildlife TV to Observational TV Documentary, Docusoap, Reality TV, Transformational/Makeover TV, and others.

The module starts off with an examination of what we term ‘Informational’ factual TV programming; those traditional genres that have been a feature of TV from its earliest days, and which traditionally were the preserve of Public Service Broadcasters. These programmes/genres aimed to be responsible, educational and informative. So, for ‘Informational’ factual TV genres the first 4 lectures looked at Current Affairs TV, History and Science TV, and Wildlife TV. History TV and Wildlife TV are deserving of having their own modules because they have shown huge developments and change in recent years that indicate both niche and global trends in TV.

It is fair to say that students seem not to know what Current Affairs TV is, they seem not to watch any examples, and when pushed to give examples, apart from a cursory knowledge of British stalwarts of the genre such as Panorama (BBC) and Dispatches (Channel 4), they gravitate towards more sensationalist, investigative contemporary developments of the genre such as Watchdog and Stacey Dooley Investigates (BBC).

Similarly, Science and History TV, whilst more interesting and entertaining for the students, seemed to be an area that belonged to the TV viewing habits of Granddads, dads and uncles. Producers of science and history TV programmes have long suspected a mostly male audience for these programmes, and therefore they have traditionally catered for this audience. My student’s own empirical survey of the genre, whilst not in-depth, suggests not much has changed in terms of audience viewing habits. This despite a wide-range of strategies created by broadcasters and producers in order to appeal to a more modern diverse audience. These strategies – niche histories, forgotten histories (Black Histories, Gay Histories, Women’s Histories) – along with ‘entertainment values’ (Pop Histories) have produced a wonderful selection of contemporary history TV programmes and in the process have prompted some wonderfully insightful research on the subject. De Groot’s study of popular history on television (2006), Bell & Gray’s studies on female historians and female TV history presenters (2007), and Hunt’s study of TV history and identity (2006), amongst others, are worth reading in terms of changes in the TV landscape in general. Perhaps most revealing about my student’s attitude towards History TV is that not one of them in this year’s cohort had seen the BBC’s Who Do You Think You Are? – an extremely lucrative and popular global franchise. Scandalous.

However, in terms of ‘Informational Programming’, the examination of Wildlife TV in the module has been a pleasant surprise. In both last year’s cohort and in this year’s, students have engaged with Wildlife TV in ways that are second only to the lectures on Reality TV and Makeover TV. I blame David Attenborough and his BBC, ‘Blue-Chip’ Blue Planet Wildlife TV extravaganza. There is no doubt that the BBC’s production of what Dingwall & Aldridge (2003) describe as ‘Blue-Chip’ Wildlife TV programmes has had an impact on the genre and has made Wildlife TV very popular both with audiences and producers alike. However, for a factual TV genre that has been around for long time, very little has been written on the genre until relatively recently. Also, there is more to Wildlife TV than ‘Blue-Chip’ examples. Key researchers on the genre include Bousé (2011), Horak (2006), and Kilborn (2006) and the essential Dingwall & Aldridge (2006). For Dingwall and Aldridge Wildlife TV can be split into 2 common types – ‘Blue-Chip’ Wildlife TV (Expensive/High Production Values, Global), and Presenter-led Adventure Wildlife TV (Cheaper, locally produced). However, this description does not do justice to the wide variety of programmes out there. Further, as Horak observes with the introduction of many dedicated channels in nature and wildlife TV and with cable TV, with its insatiable demand for content, wildlife documentaries have become ever more popular and ever more numerous.’ (Horak, 2007, p. 460). Wildlife and nature programmes are a popular and profitable genre. This is evidenced not only by the number of channels and programmes dedicated to wildlife and nature, but by the different forms they take, and the numbers involved.

Dingwall & Aldridge (2006) observe that, Discovery Communications claim that their Animal Planet channel is available in 87 million US homes and another 150 million in 160 other countries. The National Geographic channel broadcasts in 27 languages to 230 million households in 153 countries. The BBC’s The Blue Planet was sold to over 40 countries within a few months of its release (BBC Worldwide, 2002). Writing in 2007, Jan Horak observes how ‘American television offers animal documentary programming almost 24 hours a day, seven days a week.’ (2007, p.470). Citing the American cable network Animal Planet, Horak observes how it not only consists exclusively of animal shows but content ‘which in terms of their narrative construction and style, mimic… [and even parodies] regular television fare.’ (2007, p.470). Examples include: News and magazine programs (The Most Extreme on the Planet), Variety programs (Pet Star), Crime dramas (Animal Cops, Houston), Reality shows (Jeff Corwin Experience), Comedies (The Planet’s Funniest Animals), Hospital soap operas (Emergency Vets), and family programs (That’s My Baby). Variations on all these types of programmes can found at local/national levels of wildlife TV programming. They provide excellent examples of how both Wildlife TV and factual TV have developed and changed, incorporating entertainment values to meet the demands of more modern TV audiences.

This genre provides a vast amount of materials and debates to examine, a great opportunity to introduce examples (clips), and the potential to look at both global and national dimensions of factual television, and I haven’t even started on the BBC’s much beloved Spring Watch, Autumn Watch, etc. More importantly, unlike Current Affairs, and Science and History TV, students feel they know Wildlife TV, or at the very least, they seem to watch Wildlife TV.

Conclusion

There is not enough room here to discuss the rest of the module – Observational TV Documentary, Reality TV, Makeover TV, etc. – and so I will leave these for another time. However, as Hill (2007) observes, factual TV is a significant area of study because in the contemporary television landscape ‘Popular factual genres are not self-contained, stable and knowable, they migrate, mutate and replicate.’ (Hill, 2007). Popular contemporary factual television can tell us something about media production practices, viewing strategies and audiences. The other overarching view of factual television content is that it contains facts and provides knowledge about the world.

However, the need to attract audiences, and the dynamics of multi-channel TV has seen a need to make factual TV entertaining. Some modes and genres of contemporary factual TV, such as Reality TV and Docusoaps, raise questions and debates concerning authenticity, reality, and truth. Some, such as Makeover TV raise ethical concerns. Contemporary Informational programming, such as science, current affairs, or history TV, often move between two concepts – education or entertainment? New technologies, such as ‘Fixed-Rig’ set-ups, have not only changed the way some factual formats are filmed, but also the type of content being shown and viewed. And as Hill (2007) has observed, some genres and formats of factual TV, raise ethical debates concerning surveillance, exposure, and intervention; but also social issues concerning race, class, gender, and sexuality. And some factual TV formats, such as Reality TV, have changed the industrial and economic nature of TV broadcasting. But this last category can be left for a future blog.

Kenneth A Longden is a Lecturer in Television and Media, University of Salford, and a Fellow HEA.

Bibliography

Bell, E., & Gray, A. (2007). History on television: charisma, narrative and knowledge. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 10(1), 113-133.

Bouse, D. (2011) Wildlife Films. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

De Groot, J. (2006). Empathy and enfranchisement: Popular histories. Rethinking History, 10(3), 391-413.

Dingwall, R., & Aldridge, M. (2006). Television wildlife programming as a source of popular scientific information: A case study of evolution. Public understanding of Science, 15(2), 131-152.

Hill, A. (2007). Restyling factual TV: audiences and news, documentary and reality genres. Routledge.

Horak, J. C. (2006). Wildlife documentaries: From classical forms to reality TV. Film History: An International Journal, 18(4), 459-475.

Hunt, T. (2006). Reality, identity and empathy: the changing face of social history television. Journal of Social History, 39(3), 843-858.

Kilborn, R. (2006). A walk on the wild side: the changing face of TV wildlife documentary. Jump Cut, 48.

Fascinating stuff! I’ve never really ever looked at ‘Factual Television’ in any depth for research, although I’ve enjoyed a fair bit of it in my time. The anecdotal research from the current crop of viewers is also *very* interesting and quite eye-opening; it reminds me that in my own areas of research it’s vital that I keep aware of what younger people involved in the sub-culture are watching and talking about, and understanding why it engages them (or not).

Very enjoyable! Many thanks! 🙂

All the best

Andrew

Thanks. I’m glad you found it interesting

It’s interesting to see how differently people engage. I taught a module on this for the first time in 2014, at Indiana University, and reading this am getting some ideas for an update. 😉

But I’m also wondering how you split reality, obs-doc, and make-up, the latter two which I would always place underneath the heading reality… next conference let’s chat 🙂

Also: reality TV has legitimacy not because respected academics talk about it, but because for the programming in question’s impact not enough do.

I find that the most interesting here, that you built this piece on an opening that identifies legitimacy to talk factual/reality. We have so much work to do!