In August 2017, The Wrap published an article written by Kai Cole, architect,actor and producer who was married to producer, writer and director Joss Whedon for 16 years. Under the title “Joss Whedon Is a ‘Hypocrite Preaching Feminist Ideals,’” , Cole claimed that Whedon had a series of affairs with young women he worked with in the film and TV industry while married to her. This sent shockwaves through various fan communities, and, the following day, long-running Whedon fan site Whedonesque effectively closed down with the following announcement:

Cole’s accusations towards Whedon have since been eclipsed by the revelations regarding Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein In October 2017, he was accused of sexual harassment, sexual assault and rape by growing numbers of women, and men. Weinstein was fired from the Weinstein Company’s board of directors and expelled from the Academy Of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The allegations against Weinstein became headline news in various countries, sparking debates about sexism and misogyny within Hollywood and more broadly, and the way it is often excused, ignored and therefore enabled by those working in the industry. Actor Tippi Hedren’s tweets in support of those coming forward to accuse Weinstein, comparing him with Alfred Hitchcock, indicating how endemic this behaviour is in Hollywood, and how it is widespread, even integral, in its system both historically and into the present.

The sheer number of those coming forward to accuse Weinstein, coupled with his inadequate response, and—of course—his reputation as a producer and co-founder of Miramax, means that the ‘news’ about Weinstein has eclipsed the revelations Cole made about Whedon. Clearly, whilst both are abuses of authority and power, having affairs with work colleagues is not the same as persistent harassment, assault and rape. . Moreover, many commentators seem to have taken the allegations against Weinstein as simply the public disclosure of an open secret; by comparison, Whedon’s ‘betrayal’ or ‘hypocrisy’ elicited emotional, conflicted, and confused responses. The difference seems to lie in the way Whedon, or the Whedon brand, was rooted for many viewers and fans, in ‘feminism’. This is encapsulated in The Wrap’s opening quotation from Cole : ‘He used his relationship with me as a shield … so no one would question his relationships with other women or scrutinize his writing as anything other than feminist.’

For many fans and followers of Whedon, this was the crux of his hypocrisy: he claimed to be a feminist and to use ‘feminism’ in his creative work—starting with TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003)—and ‘feminism’ or a particular take on gender representation was certainly used to promote subsequent productions. No one ever imagined Weinstein to be a feminist; apparently many saw Whedon as one and were bitterly disappointed when they seemed to be proved badly wrong. The titles or headlines of articles alone set out the allegiances (and emotional responses) of their authors, from ‘Clementine Ford: Why Joss Whedon’s treatment of ex-wife Kai Cole matters’ to ‘Buffy’s Legacy Does Not Belong to Joss Whedon’.

I am Vice President of the Whedon Studies Association, an association devoted to the academic study of Whedon’s work, and an academic whose first monograph was about gender and Buffy (Sex and the Slayer, 2005). My work is perpetually informed by feminist theory and feminist thought and I find I have mixed feelings about this issue myself. And here’s one of the things that seems to me to be tricky about working out what, if anything, to think about these revelations: academic analysis and publication is not supposed to ‘feel’ anything, it is traditionally supposed to present objective examination and evaluation. I say ‘supposed to’ because I have never believed in academic objectivity and I am acutely aware of how my various identities, personal and professional, inflect my ‘feminist’ perspective and my academic work. To me, critical examination and personal investment need not be mutually exclusive. Members of the Whedon Studies Association have always attempted to offer critique and rigorous analysis and the organisation and its members have often found themselves having to defend the notion that they are not simply fans of Whedon who adore everything he produces, and accept everything he says publicly at face value.

One of the issues most debated on the WSA Facebook page following Cole’s revelations about Whedon’s personal life was how to distinguish between personal and professional, or between creator and their work. Should we re-evaluate whether Buffy (and other Whedon productions) was ground breaking in terms of how it represented ‘strong women’? Or should the personal failings of its named creator be considered separately from the impact of the TV series and films that made his name?’ One thoughtful response was Matthew Pateman’s blog, ‘Celebrity Culture, Brand Whedon and the post-Romantic fallacy,’ which notes how in many discussions or judgements ‘the semi-sainted Whedon of Equality Now and Planned Parenthood has been assumed to be identical with the legally named owner of rights to television shows.’ Pateman delineates the complexities involved in unpicking the various ‘Joss Whedon’s, concluding ‘Buffy hasn’t changed and to think it has is to oddly privilege Whedon as the sole arbiter and purveyor of its meaning. Even in the days of ‘St Joss’, that was always a fallacy.’

So what can I draw from these complex and often painful discussions? Here are some of my initial conclusions:

- ‘Feminism’ does not have a clear definition and means different things to different people. Like any perspective or ideology it can be used for different purposes and co-opted by those whom others may not consider ‘feminist.’

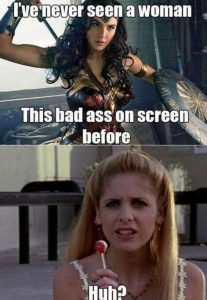

- Buffy has had an impact, on viewers, and on representations, as widely circulated memes demonstrated recently.

It wasn’t perfect, of course.

- Whether we credit Whedon or others (such as Jane Espenson or Marti Noxon) for this impact does not change it.

- In 2017, 20 years after it first aired, Buffy’s ‘feminism’ is dated because feminism, society, and television drama have moved on and developed, though arguably it is still relevan

- Studies continue to show that while productions featuring female protagonists are more commercially successful than those featuring males, such productions are far from common.

- Sexual harassment, assault and rape are all too common for many women and other people in everyday life (as evidenced by online campaigns such as Everyday Sexism and the recent #MeToo hashtag).

- Men exploiting positions of power via affairs, sexual harassment, assault and rape are not uncommon within major institutions. Such institutions may express surprise when these practices are revealed but do little to discourage them.

- Studies also show that the film and TV industries in the UK, US and elsewhere, are far from diverse, rather they are deeply unequal and dominated by white men.

I wish to remain hopeful about the future of feminism and a future that values girls, women, and those with minority identities. Therefore, I need to believe that series like Buffy can continue to inspire those who watched it to think differently about gender and the inequities of power that structure gender roles, irrespective of whether some of those involved in creating it have taken advantage of these inequities while purporting to challenge them. I need to believe that feminism can bring people together to work for effective change even as it troubles, disturbs, and upsets how we see things. Whedon and Weinstein are individual examples of what unequal systems and societies can produce. I need to believe that, collectively, we can learn from the disturbing stories about such individuals and start upsetting the system that enables them.

Lorna Jowett is Reader in Television Studies at the University of Northampton, UK. She focuses on gender, genre and representation in television, film and popular culture. Her latest book is Dancing With the Doctor: Gender Dimensions in the Doctor Who Universe and she is co-author with Stacey Abbott of TV Horror, author of Sex and the Slayer, and editor of the collection Time on TV.

This blog first appeared on the Women’s Film & Television History Network (WFTHN) website on 11 November 2017. Thanks to both Rona and Lorna for allowing us to reprint.