Viewer classification has been central to audience research and measurement since the early years of television. Efforts to gain knowledge of the viewing public have depended upon a system of classification and categorisation that segments and delineates the viewing public into recognisable social groups that can be used to steer programme policy and planning. Age, sex, location, ethnicity and occupation were assumed to determine taste, interests and viewing habits and data on these groups became (and remains) a commodity valuable to broadcasters who can make ‘informed’ decisions about current and future programmes on the basis of the knowledge developed via audience research and measurement. In the context of television audience research, the use of large scale sampling and viewer classification introduced scientific rationalism to what had previously been quite a mysterious public. In the case of the BBC, for example, early efforts to understand viewer taste through the solicitation of letters from viewers was somewhat inconsistent and did little to identify specific trends and patterns of television viewing. In the BBC’s experimental television service during the 1930s, the television department largely relied on such letters from viewers and other ad hoc qualitative forms of viewer feedback (for example, the BBC’s 1939 Television Tea Party, which invited viewers to attend a conference where they could question the television staff).. This did less to help the television service understand its viewing public, and subjected programme makers to a great deal of critical feedback. The introduction of systematic sampling by the Audience Research Department allowed the BBC to discipline the viewing public into the television audience. Classification provided one means of simplifying a complex and diverse public into a manageable and knowable audience.

In addition, this was not knowledge for knowledge’s sake. The findings of audience research were put into practice. Classifications became meaningful and resulted in certain ways of understanding the viewing public, particularly in terms of gender. For example, in both early radio and early television research women were interpreted as daytime listeners and viewers. The 1937 Report on Variety Listening Barometer[1] and the 1948 Listener Research Report- Television: Some Points about the Audience[2] suggest that women listened and watched more in the daytime when compared to men. However, when one looks at women’s listening and viewing across the day, their listening and viewing were much higher in the evening compared to the morning . Yet, because women’s viewing was compared with men’s, the interpretive framework that resulted understood women as watching more rather than less during the daytime. We can see the consequences of this on programme planning into the 1950s whereby women’s programmes were eventually taken from the evening schedule and broadcast only in the daytime. In other words, the data was interpreted in such a way as to misrepresent women’s listening and viewing and the female audience was given a particular and lesser value. Women’s programmes were broadcast at a time of day when the total potential female audience would not have access to them (since many women were either in employment outside the home or engaged in household work away from the television) and were broadcast at a time of day that wouldn’t, it might be assumed, interfere with men’s viewing.

This may seem distant from contemporary digital measurement practices, yet the legacy of the television audience research on the sex-composition of audiences, such as that undertaken at the BBC, has had very real impacts on newer forms of institutional knowledge production on audiences so much so that sex classification plays a central role in how vast numbers of users are understood, analysed and acted upon. Search engines, social media and online viewing platforms all depend upon the use of algorithms that interpret digital behaviour and it is possible to see how gender emerges as a classification, even if the algorithm isn’t intended to specifically identify and act upon gender. For example, in tracking the viewing habits of an online viewer in order to personalise their experience, online platforms such as Netflix or BBC iPlayer may use very simple recommendations. If the user watches cookery shows or police dramas, further cookery shows or police dramas might be suggested. However, if we use the example of Netflix, we can see that certain viewing activities are given meaning through gender classification. If our online viewer watches a police drama with a female protagonist, not only are they recommended further police dramas but further police dramas with a ‘strong female lead.’ (Arnold, 2016) In other words, gender remains an interpretive framework through which viewing is managed. This produces what John Cheney-Lippold refers to as a “new algorithmic identity” where online users are assigned identities that are produced from their internet use (2011: 165). Referencing gender specifically, Cheney-Lippold suggests that these algorithmic identities produce a “form of statistical stereotyping” that is imposed on the user (171). This imposition materialises in a narrow catalogue of recommendations that reflect this algorithmic identity, one where cookery show viewing operationalises the classification ‘female’ and police drama, ‘male.’ This represents a sophisticated refinement rather than a move away from the methods and tendencies of audience research as it developed in the early years of television. Such classifications simply re-inscribe the very gender-based stereotypes that audience research itself has more recently moved beyond. In other words, algorithmic logic can be used to reinforce and replicate the institutionalization of gender bias in programme planning and the customisation of services.

Complex recommendation and personalisation engines are championed as the most advanced form of audience measurement. Some go so far as to claim that they will make redundant the use of traditional demographic classifications altogether. A Netflix spokesperson, for example, claimed that:

“We have seen that where you live, gender, age and other demographics are not significantly indicative of the content you will enjoy…Time after time, we see that what members actually watch and do on the service transcends the predications of stereotypical demographics.”

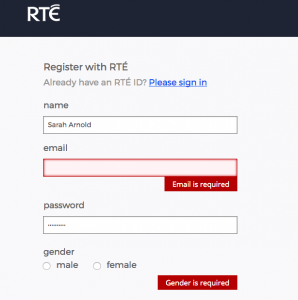

Despite this claim to overcome the stereotypes produced within traditional audience measurement, it is clear to see that gender remains a key form of audience classification on television streaming platforms. Broadcaster platforms such as the BBC and, in my country of Ireland, RTÉ continue to request the sex of its users upon registration (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).

In the case of the BBC this is both voluntary and allows for a third option whereby the user isn’t forced to select either male or female. In the case of RTÉ and many other players, the user must disclose their gender in order to complete registration (see Fig. 3)

The BBC is relatively transparent about what data it uses and provides a clear and easily accessible account of when it uses user data such as the user’s gender classification (see Fig. 4)

It suggests that such data enable the BBC to personalise the service for the user and to recommend “things we think you’ll like, like TV and Radio programmes.” Yet there is far less information on how it correlates gender with taste and what it understands the very classification of gender to mean. Neither gender nor sex are stable concepts, as recent advocacy for the recognition of more diverse gender identities has demonstrated. Male and female are increasingly understood as concepts that are as much an imposition on as an exposure of identity and are loaded with meanings that are currently contested. As such, one might ask what use the BBC, and other streaming platforms, put gender classification to. Digital platforms allow for the measurement of use, behaviour and interactions without the need for sex and gender classification. It is possible to identify the taste preferences and trends of a particular user without prescribing users’ gender identity. But gender and sex remain important to broadcasters seeking knowledge about their audience, whether it be to understand wider or more long term viewing trends or whether to leverage advertising revenue. It is, undoubtedly, possible to rationalise the use of gender and sex classification in commercial terms but this may be unproductive in terms of society. The power dynamics inherent in gender and sex classification remain subject to intense criticism and, more than ever, the media industry’s treatment of, and disregard to, women indicates that broadcasters, studios and media producers have failed to understand the implications of this power dynamic. It may be much simpler to look back and reflect on the consequences of gender and sex classification in early television but the continued deployment of such classifications suggests that perhaps not much has changed.

Bibliography

Arnold, Sarah. 2016. ‘Netflix and the Myth of Choice/Participation/Autonomy.’ In Kevin McDonald & Daniel Smith-Rowsey (eds) The Netflix Effect: Technology and Entertainment in the 21st Century. London: Bloomsbury.

Cheney-Lippold, John. 2011. ‘A New Algorithmic Identity.’ In Theory, Culture & Society. 28(6), pp 164-181)

Sarah Arnold is Lecturer in Gender & Production Studies at Maynooth University. She is preparing the book Television, Technology and Gender: New Platforms and New Audiences. Her previous books include Maternal Horror Film: Melodrama and Motherhood and the co-authored Film Handbook. Her research focuses on viewing spaces and environments of television and film, particularly in the context of gender and emergent technologies. She is a regular contributor to the Critical Studies in Television blog.

Footnotes:

[1] BBC WAC R9/9/1 A Report on the Variety (Light Entertainment) Listening Barometer October-December 1937 29th November 1937

[2] BBC WAC T1/6/2 Audience Research Memos: A Listener Research Report- Television: Some Points about the Audience 1948