Elke Weissmann starts, David Leventes Palatinus continues. Please feel free to chip in.

A few years ago my wonderful supervisor, Christine Geraghty, asked me what my experience was of speaking to other academics about television. My experience was fine – people seemed interested and polite. They spoke about programmes that they enjoyed and compared their experiences to mine. This seemed like progress, at least in comparison to the times when Christine had been involved in the BFI Women and Film Study Group, which ended up looking at Coronation Street. They had often been greeted with disdain for looking at such a low cultural form. But then I didn’t look at a feminised soap opera, but at a crime drama which at the time at least was hailed as quality, even if it was just a ‘quality of the surface’, which meant it looked more ‘like cinema’. Since then, quality TV has attracted quite a lot of interest, and I think I’m not the only one pulling my hair out as a result.

My first experience of what this attraction could lead to was shared by the equally wonderful Helen Wheatley. We both were quite interested in a panel on ‘The New TV Serials’ at a large, international conference. Reading the headline description, it sounded as if the panellists wanted to engage with questions of serialisation, flexi-narratives and televisuality, but with a sustained focus on then contemporary dramas such as Alias (ABC, 2001-2006). However, shortly after the panel began, the following things happened: one panellist had decided that he didn’t have enough time to write his paper, so he just ended up talking about a film instead. Another person consistently called Alias a ‘serial’, and when asked in the Q&A what basis he had to call it a serial instead of a serialised series, he made it clear that he didn’t know what the difference between a series and a serial was. None of them addressed the issue of narrative complexity, but instead spoke – in semi-fan fashion (but not in a good, fan-scholarly way) – about what the narratives meant. I remember Helen getting increasingly annoyed. It was the first time that I realised that sometimes papers could be really rather bad.

Ever since that experience this has been my pet-hate: non-TV scholars looking at television without consulting television scholarship. I am sure you could tell me a story or two about it too. I could add a few more, including a blog which I had to ask my colleague to remove from the learning resources website for my students because it undermined my teaching (someone using the term televisuality without having – at all – engaged with John T. Caldwell’s important definition of the term). But this blog is less about sharing these stories (consciousness raising, if you will), but about asking: so, what shall we do about this phenomenon then?

Obviously, the reason why this enrages me so much (and yes, it makes me angry) is because it highlights the low status that our field continues to have in the eyes of (some of) the rest of the academy. Television scholarship is something that can be ignored, that can run in under-visited parallel sessions in poky rooms at the end of the corridor at a big conference. But this brings all sorts of problems: as Cathy Johnson highlighted in a personal conversation, it means that we continually keep talking to a relatively small group of people who we all know very well. This does nothing to broaden our horizons. Of course, there are other subject areas that are less hostile – as Liz Evans’s research project on the multi-screen home indicates. And there are some scholars who, because of their own marginal status within their fields (they might do something as crazy as audience studies of literature or film), find the context of other subject fields – including our own – a more natural fit (Martin Barker once confessed something along those lines to me). But overall, the continued ignorance of some scholars who want to talk about TV but don’t bother to engage with relevant scholarship within our field needs to be addressed.

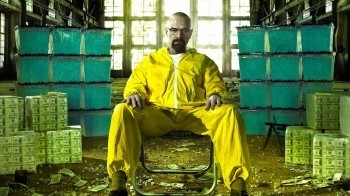

And this is why I am proposing something that I thought I would never say: let’s embrace the turn towards the interest in ‘quality TV’, but let’s use it to our advantage. As wonderful as it was that the relatively recent conference on ‘TV is the New Cinema’ aimed to challenge the debates about ‘the newness’ of the trend towards high-budget programming, ‘the exception’ that is the relationship between film and television in institution and staffing, and the inherent snobbishness of the discourses, it wasn’t able to catch those that it most needed to reach. Perhaps we have to organise more programme specific symposia (on Game of Thrones, True Detective etc.) to invite those that want to talk about TV but currently can’t. Most of all, we need to signal loudly and clearly – and I think Helen Wheatley would nod her head to that – that it is not acceptable (and that means rejecting where need be) to ignore our scholarship when talking about our field. But how can we do this when there is so much television that also needs our attention and that we haven’t gotten round to investigate yet?

David Leventes Palatinus responds:

Programme-specific symposia would provide a platform for us to investigate television we haven’t gotten round to investigate yet. A lot of recent (and often very exciting) television is born at the intersection of subversion (of genre, format, style, form of delivery) and conventionality, ephemera and perennial character, flow, participation, agency, multi-platform narrativity, etc. This might actually provide an opportunity to clearly demonstrate that television builds on (and operates within the framework of) its very own continuity while exploiting the potentials of converging media. This would also give us the chance to emphasise that the evolutionary argument that is at the apex of various histories of television (and of television scholarship for that matter) is actually predicated on a reverse logic – where it is not television that is the new cinema, but rather cinema the new television.

Elke Weissmann is Reader in Film and Television at Edge Hill University. She is currently considering changing this to Reader in Television and Film, however. Her books include Transnational Television Drama (Palgrave) and the edited collection Renewing Feminisms (I.B.Tauris) with Helen Thornham. She is vice-chair of the ECREA TV Studies Section and sits on the board of editors for Critical Studies in Television. She migrated to the UK in 2002 after realising that German television was as bad as she remembered.

David Levente Palatinus holds a lectureship in Contemporary Literature and Culture at the University of Ruzomberok. He has published on forensic crime fiction, corporeality, digital media, and violence and deconstruction. He is currently working on a booklength project called “The PathologEthics of Culture.”