When I started working for the soap operas production industry in Portugal I was always a little bit afraid of talking about it with my friends and family. No particular reason for that…just a strange feeling that I was part of something terrible: low quality television content for the masses, rubbish television. I started working mostly in production, but I later moved to something even more daunting: selling soaps! For five years or so, I worked in the international sales department of a Portuguese soap opera production company, selling both completed programmes ready to air and scripted entertainment soap opera formats to many different countries, including Russia, Mexico, Ecuador and even Brazil. Many of these international sales were completed via intermediaries, such as Disney (one of the largest brokers of soaps for the Spanish speaking markets), and, in most cases, we had to adapt the duration of the formats to local requisites. This was a challenging task. Besides going through hundreds of episodes and reediting much of the content, I also had to write the texts for the promos that had to be made for the local markets and assure all stages of the distribution process. I looked at myself and thought: not only am I an accomplice in the continuous mass production of more and more of these dreadful pieces of audiovisual content, but, even worse, I’m actively contributing to their international dissemination! My daily work is contaminating the minds and souls of people that until this moment were lucky enough not to have had any previous contact with these stories of love, treason, greed and all other emotions you can think of, taken to a state of absolute hysteria!

Only later I became aware of how naïve my pre-concepts were and how they were preventing me from understanding that the gratifications audiences took out of watching this content were much more complex, and I now dare to say, interesting, than what I initially realized. The complexities of these processes and the relevance this content had for the fruition of audiences was something that only became clearer to me later when I started to engage myself with the field of television studies.

But the question remains: why was I doing it?

After some soul searching, I found two main reasons: The first one is actually very obvious: I needed the income, a paid job. The second reason is more prosaic and I only became aware of it years later when I came into contact with soaps from the completely different perspective of a critically driven academic: I actually enjoyed it!

I think my simple personal story tells a lot about the importance of soap operas, or if you prefer, long duration serialised content, in many European countries, and the relevance they have for audiences at regional and international levels. Let us start with the issue of paid jobs: the creative industries are at the top of the political agenda in most European countries, and the European Union regards the creative industries as a key element in its policies. If you look at several reports produced through the years by the European Commission and other European bodies, such as the Joint Research Centre of the EU, they all assume the creative industries, and in particular the so called “Media and Content sector”, are nowadays fully intertwined with the ICT industries. This allowed for the emergence of new disruptive business models, all of which are primarily engaged in the creation and dissemination of information and cultural products. Nevertheless, the fact is that the known dependency on public funding in most European countries – namely southern European countries – and the low investment levels, translate into a volatile production landscape, made of small companies that live for each project at a time and lack a long-term orientation. The consequence of this state of affairs as far as employment is concerned is pretty obvious: the ability of this industry to create sustainable jobs is very faint, though getting a paid job after you leave the university with an arts or communication degree is not an easy task!

And this was the first reason why I loved soaps! They allowed me to get a paid and sustainable job. And this was true – in those days – for most of my young colleagues in the creative sector in Portugal. When I entered the industry back in the end of the 90s, soap opera – or telenovela as we call them in Portugal – production was on the rise. Telenovelas rose to the top of the domestic Portuguese television market back at the beginning of the 21st century under the leadership of private broadcasters after decades of co-existence with the Brazilian version of the genre, and have since then been the main televisual content consumed by national audiences. This growth in consumption patterns was directly correlated to a steady growth in the volume of TV hours of fiction produced. Success amongst local audiences allowed for the implementation of a sustainable and institutionalised production and distribution industry at national level, that thus was able to create and sustain creative jobs.

For me, along with sustainability came greater involvement, and new opportunities, which started to emerge as a consequence of the international distribution of soaps, that began in that period. Changes in the creative process, which allowed for the introduction of new topics and subjects in the narratives, also represented a new and exciting avenue of innovation. And that became the main reason why I loved soap operas: they allowed for experimentation with televisual formats and they allowed me to have an exposure to the international production and distribution markets, something that would have been impossible to happen in that period in any other creative sector in the country.

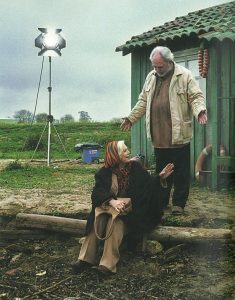

Ouro Verde (2017), Televisão Independente (TVI).

Other scholars that have studied the Portuguese version of soap operas, particularly Hugh O’Donnell, have also pointed out the relevance of innovation in the themes covered by the telenovelas to ensure the format’s local success. Similarly, to many of its European counterparts, Portuguese soaps have in the past explored themes with a local historical or cultural resonance. Engagement with issues of national identity or representations of a collective history or memory are usually presented as the main reason for the successful localisation of televisual genres, a process that happens in contra-flow with the adoption of transnational television formats. This is also true for the Portuguese telenovelas but, in contrast to the formats produced in many other European countries, it was their ability to explore (what some would consider more controversial) topics that allowed them to reach overwhelming audience success. In the last two decades, telenovelas attracted national audience shares of sometimes over forty percent and reached the incredible figure of 500 episodes between 2001 and 2003 and more than 2,5 million viewers in its last episode with a share of 44,5%. Why was I only aware of this when I, much later in life, looked at telenovelas from a different perspective, that of an academic? Because when I was working every day in the industry, overwhelmed by all the stress that television production and distribution involves, I was not aware of the very simple fact that, if it were not for the opportunities given by soap operas industry, I would never have had access to a number of remarkable experiences.

The success of soap operas has therefore had a great impact in my life. I was fortunate to be there when the market was booming and international exposure was starting. However, as I later understood while conducting qualitative research with many professionals that worked in the industry throughout this entire period, its success also had a strong negative impact on the ability of local creative professionals to evolve and do more than just produce serialised “soapy” drama. The main reason for this was that soaps monopolised the production landscape in the country and seized all talent. Their success made them so big that it did not allow for any other alternative format or production culture to emerge. This has been lasting and still prevails. 2018 European Audiovisual Observatory data ranks Portugal secondly only to Germany when we consider the total number of hours of TV fiction produced per year! In 2017, 1,354 hours of TV fiction were produced in the country and the large majority were programmes with more than 13 episodes. This explains why with only 20 different programmes – Germany produced 307 and the UK 147 – Portugal was able to produce 250 hours more fiction content than the UK. The content being produced in the country nowadays has nothing to do with high-end TV fiction, assuming the concept to correspond to series ranging between 3 and 13 episodes with a considerable budget per episode. In the Portuguese case, we are talking of long duration serialised formats – most of the times with at least 300 episodes – constantly revisiting the same themes and topics and with no narrative innovation. Concentration of all production with a small number of players is also not positive. Even if two Portuguese production companies rank in the European top ten in terms of hours produced per year, the fact is that the total number of companies operating in the country is very small, namely due to the monopoly telenovelas represent. The innovation in themes that occurred in previous periods is gone and innovation in other domains, including distribution, is scarce. Data from the same period also produced by the European Audiovisual Observatory, shows that long duration serialised content does not circulate well on streaming platforms either. At the same time, and contrarily to PBS broadcasters that favour 3-13 episodes high-end formats, telenovelas are clearly favoured by private broadcasters as a source of revenue. Having said this, it is clear that the success of telenovelas, that was so beneficial in the past, is now having a strong negative impact in the ability of the Portuguese television production sector to evolve and innovate.

The success of soap operas has therefore had a great impact in my life. I was fortunate to be there when the market was booming and international exposure was starting. However, as I later understood while conducting qualitative research with many professionals that worked in the industry throughout this entire period, its success also had a strong negative impact on the ability of local creative professionals to evolve and do more than just produce serialised “soapy” drama. The main reason for this was that soaps monopolised the production landscape in the country and seized all talent. Their success made them so big that it did not allow for any other alternative format or production culture to emerge. This has been lasting and still prevails. 2018 European Audiovisual Observatory data ranks Portugal secondly only to Germany when we consider the total number of hours of TV fiction produced per year! In 2017, 1,354 hours of TV fiction were produced in the country and the large majority were programmes with more than 13 episodes. This explains why with only 20 different programmes – Germany produced 307 and the UK 147 – Portugal was able to produce 250 hours more fiction content than the UK. The content being produced in the country nowadays has nothing to do with high-end TV fiction, assuming the concept to correspond to series ranging between 3 and 13 episodes with a considerable budget per episode. In the Portuguese case, we are talking of long duration serialised formats – most of the times with at least 300 episodes – constantly revisiting the same themes and topics and with no narrative innovation. Concentration of all production with a small number of players is also not positive. Even if two Portuguese production companies rank in the European top ten in terms of hours produced per year, the fact is that the total number of companies operating in the country is very small, namely due to the monopoly telenovelas represent. The innovation in themes that occurred in previous periods is gone and innovation in other domains, including distribution, is scarce. Data from the same period also produced by the European Audiovisual Observatory, shows that long duration serialised content does not circulate well on streaming platforms either. At the same time, and contrarily to PBS broadcasters that favour 3-13 episodes high-end formats, telenovelas are clearly favoured by private broadcasters as a source of revenue. Having said this, it is clear that the success of telenovelas, that was so beneficial in the past, is now having a strong negative impact in the ability of the Portuguese television production sector to evolve and innovate.

And this is why I now don’t love soap operas anymore… But if they again became in the future a source of creative innovation and development that promoted local original production cultures, then I would definitely love them again!

And this is why I now don’t love soap operas anymore… But if they again became in the future a source of creative innovation and development that promoted local original production cultures, then I would definitely love them again!

Manuel José Damásio is the Head of the Film and Media Arts Department at Universidade Lusófona in Lisbon, Portugal and a Member of the board of the European Association of Film and Television Schools (GEECT/CILECT). He has worked both in academia and industry for more than twenty years.