Contemporary media culture seems to suggest that it is unacceptable for a woman to look her age if she is over twenty-five. Apart from the flood of anti-aging products and procedures advertised to ever younger audiences, another key indicator for this trend can be found in the female faces presented to us in popular television programmes.

“Is that her?”, I thought to myself, as I stumbled across the latest remake of the 1970s sitcom The Odd Couple (ABC 1970-1975), in its current version on CBS (2015-) featuring Friends star Matthew Perry as the chaotic sports reporter Oscar Madison and Thomas Lennon as his uptight, obsessive-compulsive roommate Felix Unger. What shocked me even more than the show’s painfully unfunny attempt to revive a classic sitcom by turning its main characters into caricatures was the sudden appearance of a somewhat familiar female face. I had to look three times to conclude that this was actually Teri Hatcher playing a supporting role as Oscar’s neighbour and love interest, Charlotte. Hatcher, who rose to international stardom as one of the four Desperate Housewives (ABC 2004-2012) over a decade ago, suddenly looks very different. At fifty-one, her face is wrinkle-free and puffy at the same time. Upon closer inspection, I realized that the actress, like many other “older” female celebrities these days, must have undergone cosmetic and surgical procedures to achieve this unnatural look.

The Odd Couple, season 2, episode 6: Dani (Yvette Nicole Brown) and Charlotte (Teri Hatcher)

In their article “The Influence of Television and Film Viewing on Midlife Women’s Body Image, Disordered Eating, and Food Choice” (2014), Veronica Hefner et al. state that while “midlife” [1]Midlife is generally defined as “the central period of a person’s life” (Oxford Living Dictionaries, “Midlife”, 2017 [https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/midlife]), spanning from … Continue reading actresses are currently very popular in American film and television, they are increasingly “portrayed with bodies that are the shapes and sizes of much younger women […]. For example, the television shows Cougar Town and Desperate Housewives both feature women in their 40s whose bodies are more representative of women in their 20s in terms of fitness and thinness” (Hefner et al. 2014, 185). The authors hypothesize that this trend could negatively affect how female viewers, especially in the midlife age range, perceive their own bodies when compared to mediated body ideals. Similarly, with the proliferation of wrinkle-free actresses beyond the age of forty, the question arises whether these surgically enhanced faces have the potential to set a new standard for how women in this age group could, or indeed, should look.

While the number of roles available for midlife and older women is rising, even as they remain severely underrepresented, the condition for including them seems to be that these actresses cannot flaunt naturally aged faces. The Netflix comedy Grace and Frankie (2015-), currently in its third season, is the first successful U.S. show since The Golden Girls (NBC 1985-1992) to centre on women over fifty. Played by award-winning actresses Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin, Grace and Frankie are in their early seventies when their husbands reveal they have been lovers for twenty years and finally want to leave their wives to marry each other. Suddenly single after forty years of marriage, the comedy results from the two contrasting female leads being forced to live together and to adjust to the new situation. Grace is a former cosmetics executive and model whose fashionable conservative outfits and perfect make-up lend her an immaculate look in any situation, whereas Frankie is a hippie art teacher mostly dressed in flowing, colourful garments and adorned with “ethnic” jewellery. She is also one of the few female characters on American television allowed to wear grey hair – of course, Frankie’s long greying waves also serve as one of the markers of her rather clichéd alternative lifestyle. Interestingly, both Fonda and Tomlin are older than the women they play on Grace and Frankie. At seventy-seven, Fonda is seven years older than her character Grace in the show’s first season, while Tomlin is five years older than Frankie. Yet, both actresses present surprisingly smooth faces, for their real age as well as for their fictional characters’ age. Clearly, cosmetic surgery plays a role here. In an interview with The Guardian, Fonda admits, “I wish I were brave enough not to do plastic surgery but I think I bought myself a decade” (Shoard 2015).

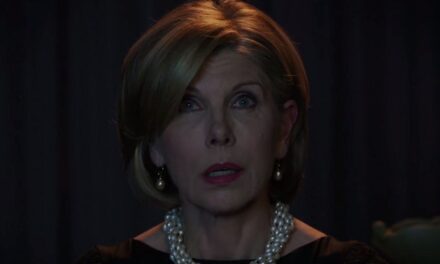

Grace and Frankie, season 1, episode 6: Grace (Jane Fonda)

Grace and Frankie, season 1, episode 6: Frankie (Lily Tomlin)

Linn Sandberg argues that discourses on ageing tend to be framed in binary ways, “either as a decline narrative or through discourses of positive and successful ageing” (Sandberg 2013, 11). Whereas decline discourses characterise old age in terms of physical degeneration and loss of independence and productivity, “[i]n successful ageing, the specificities of ageing bodies are largely overlooked while the capacity of the old person to retain a youthful body […] is celebrated” (Sandberg 2013, 11). In recent years, this concept of successful ageing has increasingly structured representations of older persons in the media. In “The Denial of Aging in American Advertising”, Erin Lamb and Jim Gentry point out that, as the generation of baby boomers retires, images of the aged in US advertisements have not only become more frequent but also more positive, particularly when targeting older audiences. However, for the most part, a certain type of older person is presented: healthy, younger-looking men and women who embody what Lamb and Gentry describe as “agelessness”, based on the denial of the visual signs of ageing and functional decline. The authors argue that this trend, promoted by the anti-aging market with products such as Botox and surgical procedures, “serves to increase our negative associations with old age, offering ‘self-empowerment’ to the individual who can still pass for young at the cost of a larger disempowerment shared by all who grow recognizably older” (Lamb and Gentry 2013, 38). This development also applies to US popular television, especially to the representation of older women. Judging from the programmes I have seen recently, it has become next to impossible to find female faces on American television that are left to age naturally. The problem is that presenting surgically rejuvenated faces as the norm rather than the exception has the potential to render the natural signs of biological age socially unacceptable. In a society that is rapidly growing older, can we afford to define the process of ageing as aesthetically undesirable? Hopefully, getting old without looking old will not become the new norm for current and future generations. After all, wrinkles and age spots can tell a story that Botox and facelifts cannot tell.

Jamila Baluch holds a PhD in Television Studies from the University of Reading. She currently lives in Berlin where she works with refugees and teaches media studies.

Works cited:

Hefner, Veronica; Woodward, Kelly; Figge, Laura; Bevan, Jennifer L.; Santora, Nicole, and Sabeen Baloch: “The Influence of Television and Film Viewing on Midlife Women’s Body Image, Disordered Eating, and Food Choice.” Media Psychology, vol. 17, no. 2, 2014, 185-207.

Lamb, Erin and Jim Gentry: “The Denial of Aging in American Advertising: Empowering or Disempowering?” International Journal of Aging and Society, vol. 2, no. 4, 2013, 35-47.

Sandberg, Linn: “Affirmative old age – the ageing body and feminist theories on difference.” International Journal of Ageing and Later Life, vol. 8, no. 1, 2013, 11-40.

Shoard, Catherine: “Jane Fonda: ‘Plastic surgery bought me a decade’.” The Guardian, 21 May 2015, https://theguardian.com/film/2015/may/21/jane-fonda-youth-plastic-surgery-sex-cannes [accessed 12 February 2017].

References

| ↑1 | Midlife is generally defined as “the central period of a person’s life” (Oxford Living Dictionaries, “Midlife”, 2017 [https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/midlife]), spanning from age 40 or 45 to 60 or 65 (see also Psychology Today, “Midlife”, 2017 [https://psychologytoday.com/conditions/midlife]). |

|---|

One of the reasons for liking Nordic television shows is that the women are consistently less made-up than in US/UK shows and older women are allowed to look older.

Great article Jamila – thank you. Thought you might be interested in our work at WAM (Women, Ageing & Media), an intergenerational research group based at the University of Gloucestershire. Find us on Twitter #wamuog, Facebook, or our homepage http://www.wamuog.co.uk. We hold a Summer School each year, it promises to be a fab 10th anniversary celebration in 2017 and the Call for Papers is live – deadline 24th March.

Thank you, Alison. I will definitely look up your research group!

Courteney Cox has talked to Bear Grylls about the cosmetic work she has done, and how she regrets it and is looking forward to some of it going away (presumably she means fillers or something like that). Very touching.

A little cosmetic tweaking can I think help a woman through a psychological bad patch ( end of marriage for instance) as a pep to her confidence. However, it would appear in some cases to become addictive? The elegant solution is I believe knowing when to stop and reap the rewards of that fresher look and move on.