With the British government’s latest diktat concerning the future of the public service broadcaster, Channel 4, now fully revealed, it is time to consider the contribution Channel 4 has made, not only to the British media landscape, but to personal and public experiences as a whole over the last 40 years.

I say both personal and public experiences because that is how television works, and Channel 4 has been influential in both respects. My own personal experiences of Channel 4 are of growth and discovery, not unlike those of the channel itself. Like me, in 1982, Channel 4 burst onto the scene like a rude, cocky, in-your-face (it wasn’t long after Punk), daring adolescent, determined to show a jaded older generation the world had changed. It was attractive and appealing for all those reasons that youth often is.

Fig. 1: One of Channel4’s first shows, The Comic Strip (1982-2011), which debuted on the opening night of transmission

My first experiences of Channel 4 were The Comic Strip (1982-2011) (debuting on the opening night of transmission), The Tube (1982-87), and offerings of hitherto unheard of rebellious and controversial (for TV at the time) programming with shows such as Richard Prior Live, and the hugely controversial Jesus: The Evidence (1985), the latter being Channel 4’s take on Religious programming. Richard Wallis, in his paper ‘CHANNEL 4 AND THE DECLINING INFLUENCE OFORGANIZED RELIGION ON UK TELEVISION’ (2016) argues how the programme “was emblematic of a growing cultural dissonance between the religious and the broadcasting institutions”.

Along with programmes such as this one, the list of TV shows that ‘revitalised’ the TV viewing experience in those early, heady days of Channel 4’s existence was a statement of intent – A Woman of Substance (1985), Brookside (1982-2003), Queer as Folk (1999-2000), Brass Eye (1997-2001), and many, many others.

Admittedly, as with the exuberance of youth, some of this revitalising of TV was hit and miss. The programme, After Dark (1987-91) was tedious television, and in the early days, tabloids referred to the channel as ‘Channel Snore’. Similarly, Channel 4’s experiment with the ‘Red Triangle’ (1986), an initiative that “gathered together a number of mostly foreign and art films linked by their reputation for sexually explicit content” (Duguid, 2007), provoked the tabloid description ‘Channel Phwoar’.

As I grew older, more worldly-wise, and (I thought) more sophisticated, so too did Channel 4. Programmes such as ABC’s Lost (shown on Channel 4 between 2005-2006), Spaced (1999-2001), Six Feet Under (2002), and many more were a phenomenon and seemed to encapsulate a changing world and my own personal affinity with the world around me. This is to ignore, of course, the other, more long-lasting phenomenon that was Big Brother (2000-2010).

But there is a more public, or more professional experience of Channel 4 to consider too. In asking the rhetorical question here – What Has Channel 4 Ever Done for Us? – I am considering the vast amount of public debate around the channel and its programming, and the vast amount of academic research that the channel has generated since its first transmission. A brief overview of some of the research papers and academic books that have been written on Channel 4 over the last 40 years not only provides an interesting history of the channel, but of the issues the channel has regularly provoked or identified with.

My own first academic connection with Channel 4 came through Catherine Johnson’s Branding Television (2011), and her now, seemingly prophetic chapter ‘The end of public service broadcasting?: branding Channel 4 and the BBC.’. In this chapter Johnson draws attention to the 1985 Peacock Committee, set up to discuss future funding of the BBC, and a curious BBC promotion featuring John Cleese asking, ‘What has the BBC ever done for us?’. Cue a long list of programmes …

More significantly, Johnson also identifies how Channel 4 programming operated under a remit that was quite unlike anything the existing channels had to consider. Freed from the ideological constraints and history that had informed the BBC and ITV, Channel 4 was innovative, inclusive, and willing to take television to places it had previously ignored or avoided; and eventually it became influential on all TV output in Britain. Reality TV, and its influence on other forms of TV, for better or worse, owes much to Channel 4.

Innovation and inclusivity (the requirement to represent diversity) were elements that became part of the Channel’s strategy to differentiate itself from both the BBC and ITV, and this not only established Channel 4 as a key driver of what Johnson identified as an era of TV branding (TV III), but Channel 4’s brand identity played on a certain kind of irreverence and daring. As Mark Duguid of the BFI observes, “Another factor in the Channel’s growing success was controversy – sometimes accidental, sometimes craftily exploited for promotional effect.” (2007).

Channel 4’s brand identity often drew criticism, not least its (for some, ‘over’) reliance on US imports. But significantly, with ‘Channel snore’ and ‘Channel Phwoar’ left behind Channel 4’s association with ‘Quality TV’, in particular, The Sopranos (2000), and close association with HBO, brought financial success, and a success that is not entirely removed from Channel 4’s original remit.

Catherine Johnson observes how as with HBO, Channel 4 made a commitment to screen the kinds of television programming not found elsewhere on British television. As with HBO, Channel 4 has a remit for creativity and innovation in its programming. In fact, since 1982 Channel 4 has been making or showcasing television that matters—offering an alternative to the mainstream on other channels even if the “placing a premium on innovation, originality and diversity’” is not always home-grown (Johnson, 2007, p.12).

Paul Grainge, in his paper ‘Lost logos: Channel 4 and the branding of American event television’ (2009) observes how regardless of criticism, “there is no doubting the importance of American programmes to Channel 4’s survival and market success, helping it to achieve 10 per cent of the total audience share by 2001, rivalling BBC 2 (11.1 per cent) and outperforming Sky (6 per cent)” (2009). Grainge also identifies how the 1990 Broadcasting Act, which allowed Channel 4 to sell its own advertising, placed an emphasis on popular programming changing the dynamics of the channel. Also, the legacy of Michael Grade, who steered Channel 4 between 1988 and 1997, was significant in leading to the reduction of experimental minority output and the promotion of American entertainment imports “able to generate the markets sought after by advertisers” (2009).

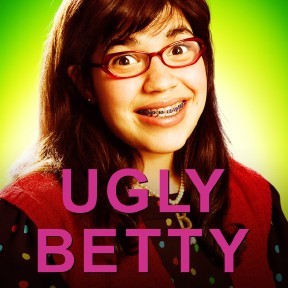

Think of the impact on the British TV viewing experience, as well as academia as a result of shows such as Roseanne (ABC, 1988-1997), Friends (NBC, 1992-2004), Ally McBeal (Fox, 1997-2002), Sex and the City (HBO, 1998-2004), Ugly Betty (ABC, 2006-2010), Hill Street Blues (NBC, 1981-1987), ER (NBC, 1994-2009), The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006), and many others.

Fig. 2: Ugly Betty (ABC, 2006-2010), premiered on Channel 4 on January 5, 2007, attracting 4.5 million viewers.

What has Channel 4 ever done for us (academics)?

On a different note, Paul Giles has examined the impact of Channel 4 on British filmmaking. In his study, ‘History with Holes: Channel 4 Television Films of the 1980s’ (2006), Giles argues that Channel 4’s innovative approach to filmmaking and film production, both in the ‘Film on Four’ series, and with ‘Film Four International’, charted a new direction for film on television, “bridging general accessibility with the power to reshape people’s perceptions…” (2006).

Similarly, Andrews (2014), in his study ‘More than a Television Channel’: Channel 4, FilmFour and a failed convergence strategy’ has examined Channel 4 in relation to the rise of convergent television in the UK, through a case study of Channel 4, throughout the 2000s, with particular focus on the filmmaking arm, FilmFour.

The list of research on Channel 4 is almost endless.

If Channel 4 has offered anything to anyone then it is surely those of us who belong to the TV/Media academic community.

Is this an elegy? I sincerely hope not.

Kenneth A Longden is a Lecturer in Television, Film and Media, University of Salford, and a Fellow HEA.