As Robert Lindsay notes in his autobiography Letting Go, by the late 1980s, things weren’t looking so well for his career: following an difficult stint in the USA, where he had worked on the film Bert Rigby, You’re a Fool (1989), the actor who was known for roles such as Wolfie Smith in Citizen Smith (BBC1, 1977-1980) and had enjoyed success both in the West End and on Broadway, returned to Britain with little of that most crucial commodity a performer needs for their craft: self-confidence. As he put it: ‘I was shattered; my self-esteem had completely gone. […] I was completely lost from a career point of view; I was thinking of giving the whole thing up.’ (Lindsay 2009, 205-6) Then came the opportunity to play a character named Michael Murray in G.B.H. (Channel 4, 1991), a part written by Alan Bleasdale with Lindsay in mind. With Murray a corrupt, haunted, twitching, loathsome and tragic city council leader, located within a script with surreal overtones, this was certainly a challenging part for any actor to take on, never mind one who had lost faith in his ability to act – and Lindsay went on to produce a memorable small screen performance that deserved the BAFTA he won for best actor, and still deserves, if not demands, some detailed critical attention that looks at how he engaged with this acting challenge.

Given the richness of Lindsay’s performance, we will focus our attention on one short moment towards the end of episode 4 (‘Message sent’), which readers located in the UK can enjoy in full here. Under increasing professional and personal pressure, stressed Michael Murray leaves the hotel lobby where a Doctor Who convention is taking place. This is perhaps the most commonly remembered scene from G.B.H, because of Alan Bleasdale’s in-joke for Verity Lambert, and can also be watched here:

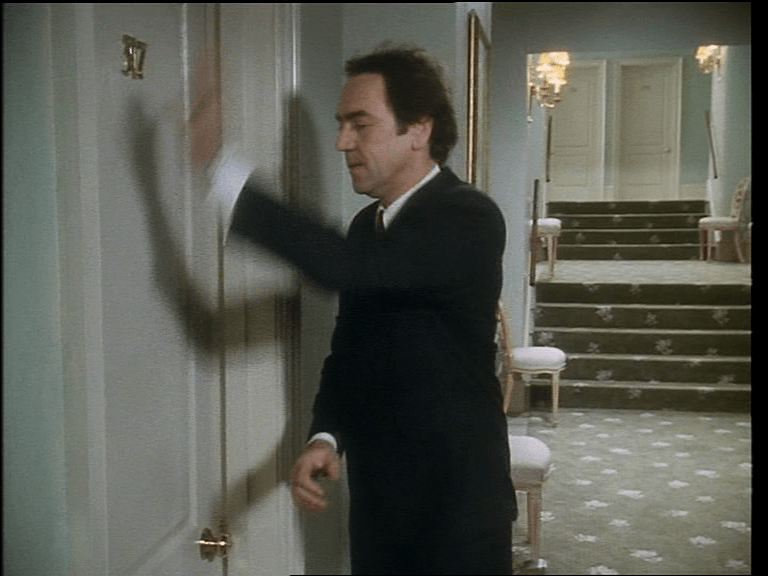

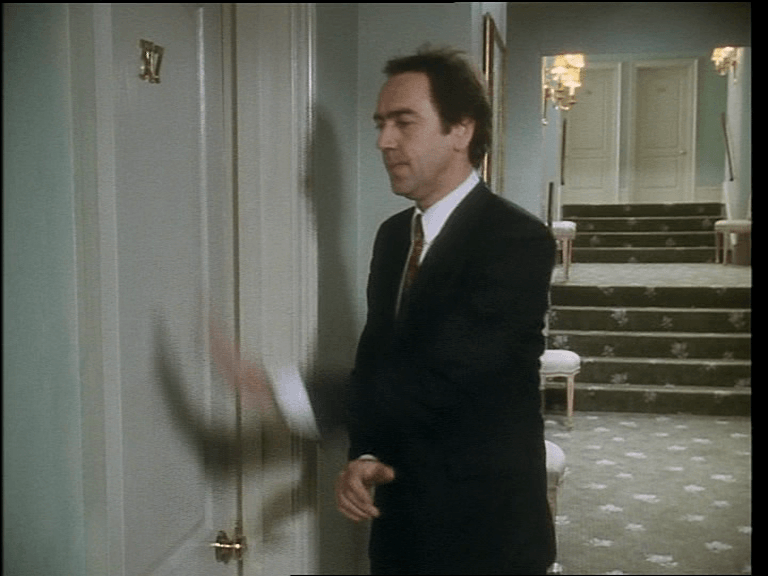

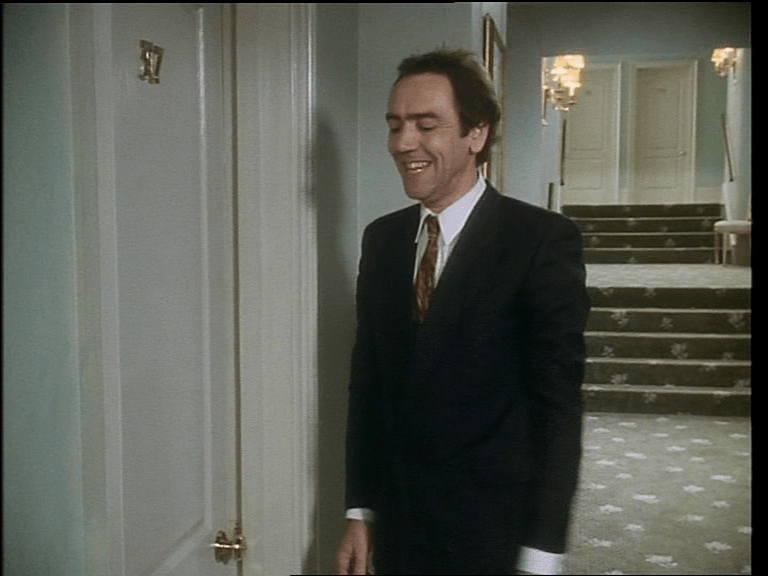

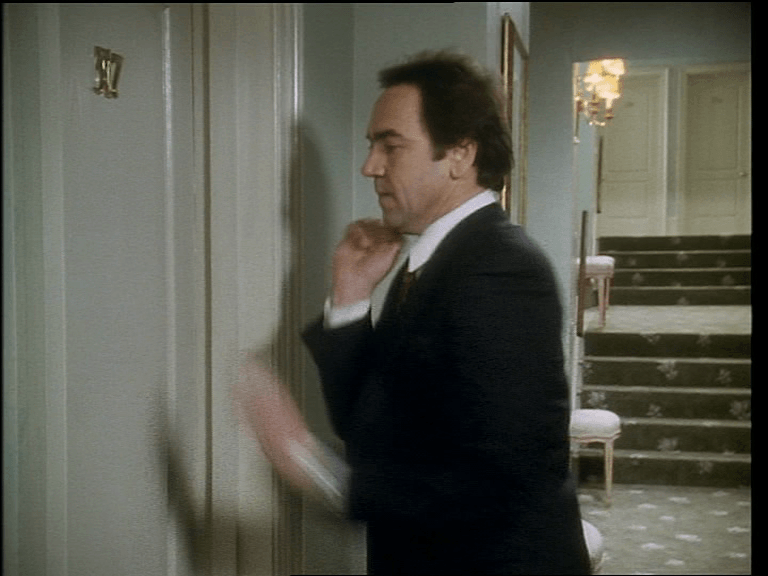

Having secured condoms and ordered champagne, Murray makes his way upstairs to spend the night with love interest Barbara Douglas (Lindsay Duncan). At just over an hour into the episode (to be precise, 1.00.25 on 4OD, 1.01.25 on the DVD), the moment that fascinates us takes place when he walks through the hotel corridor and arrives at Barbara’s room. Here, in the space of one extraordinary minute and one uninterrupted take, Murray’s physical twitch, which originated as a wink and was already getting in his way during the Dalek scene, interrupts his attempt to knock on the door. To steady his nerves, he backtracks to take a run-up to the door, trying to talk himself back into the (albeit faux) confident swagger with which he first arrived. There are many, many performance choices by Lindsay worth paying attention to here, as he verbalises and involuntarily physicalises his interior monologue and turmoil, calling up subtle intertextual references to John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever (1977) and Fonzie from Happy Days (ABC, 1974-1984), interweaving performative elements of football, dance and musical theatre, and working both with and beyond the script in what Alan Bleasdale in the ‘Interview’ DVD extra calls a ‘moment of lunatic improvisation’.

One of the subtle intertextual references called up by Robert Lindsay’s acting

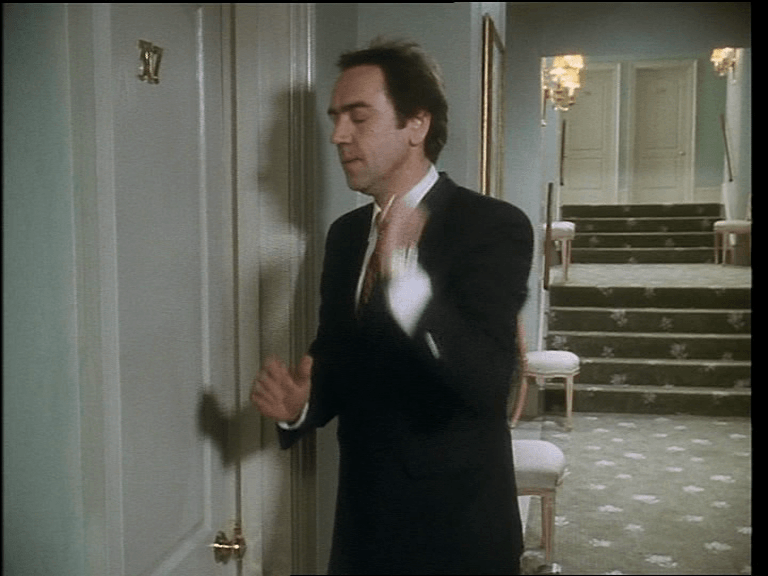

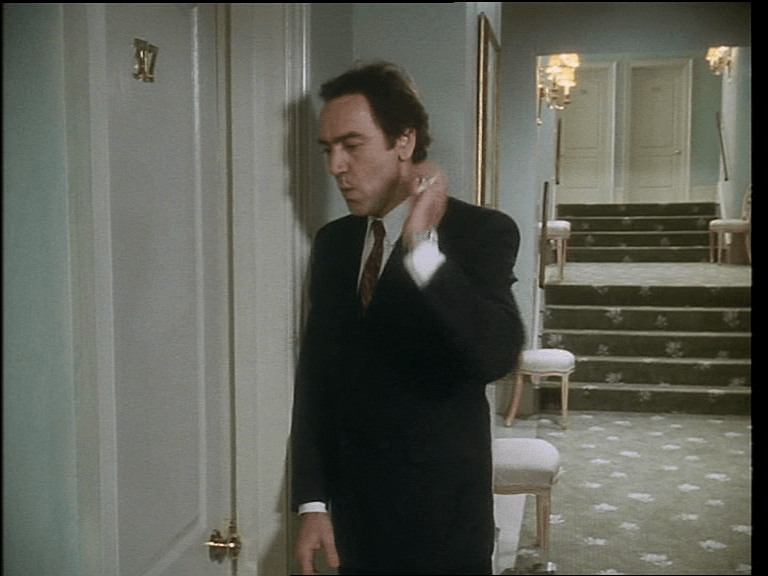

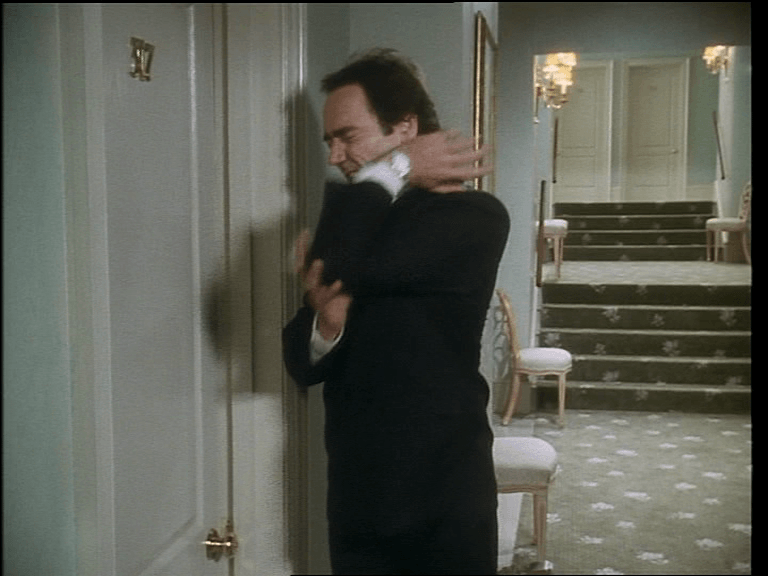

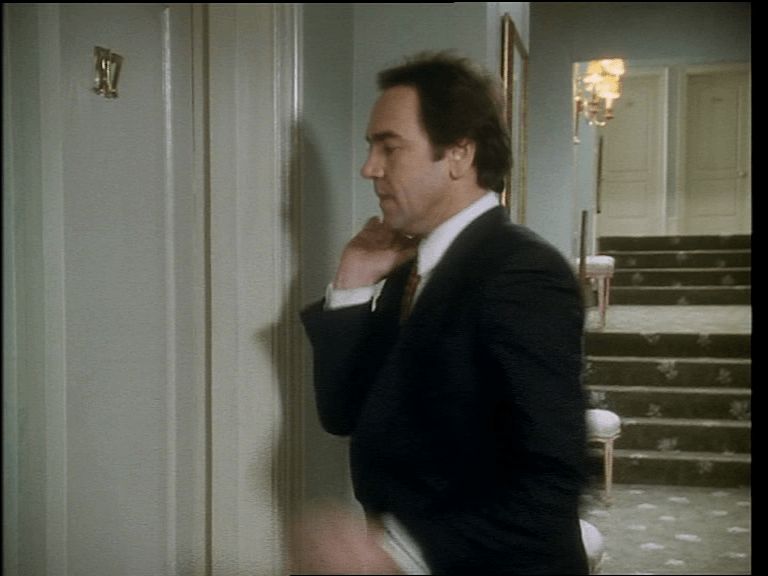

For the purposes of space, we will for now focus on the perhaps most widely remembered aspect of Robert Lindsay’s performance as Michael Murray, the twitch. The following screen shots give a flavour of this:

In Letting Go, Lindsay notes that while the twitch had been written into the script by Bleasdale, the production team was concerned that this tic was not rooted in any reality, and that he, Lindsay, had ‘to make it as real as possible’ (2009, 207).[i] So, how does he approach this task here in this scene? Firstly, Lindsay begins the scene evidently having prepared himself physically for it, perhaps bearing in mind Stanislavski’s advice that, ‘[i]f [the] preparatory work is right, the results will take care of themselves’ (1989, 212). Following the Stanislavskian emphasis on getting into character, he both taps into the nervous energy that can naturally occur in performers before shooting and has, through some physical exercise before the take, built up a slight sweat and near-hyperventilation. Out of breath and perspiring, this preparation allows him to enter the scene at the right – in this case, edgy – energy and performance level, where the would-be confidence of his initial approach readily gives way to the anxiety the character was feeling in the previous scene.

When Murray’s attempts to knock on the door are prevented by his left arm spasming upwards, Lindsay manages to convey Murray’s loss of control over his own body through careful acting that brings together this twitch with a whole host of other small actions, or outer characteristics – such as deep breaths out, talking to himself, whistling, stretching the arm downwards as though trying to ease a cramp – into an organic sequence where these different actions trigger one another as he attempts to calm himself down whilst still at the door. Lindsay further makes the twitch and these other actions look integrated into the character because he (mostly) looks like he is genuinely in the moment, surprised and appalled by and apparently unable to predict what this ‘demon hand’ of his is doing.

Because of this organic quality of the performance, it may seem tempting to think of Robert Lindsay’s acting here as further drawing on the Stanislavskian approach where ‘in each physical act there is an inner psychological motive which impels physical action’ (Stanislavski 1968, 11), and one’s character is found through psychological and emotional engagement. However, we wish to propose that this is actually a very technical performance here, where the portrayal of the loss of control requires such careful control, such precision (of timing, of movement, of physical distance to the door) and involves such business (with repeated near-knocks and attempts at calming down, there are many outer characteristics for Lindsay to manage in a very short time), that the Stanislavskian mode would not be entirely appropriate. A Stanislasvkian approach to acting proposes that ‘it is a necessary condition of the unfettered operation of the subconscious that conscious awareness be actively supressed during the creative act’ (Mitter 1999, 16). Or put another way, as long as you are in the moment, the details of the acting, the outer characteristics, will take care of themselves, and the performance will just happen. However, the demands of the role here are such that Robert Lindsay is employing a technically precise imaginative performance, whereby he makes his actions look real, organic and happening against his will and appears to be genuinely in the moment, through external means, thinking and planning. His autobiography confirms this careful planning through his reference to working closely with the continuity girl. (See Lindsay 2009, 207.) This resonates with Chekov’s approach to acting, where ‘[t]he task of the actor is to become an active participant in the process of imagination, [bringing] the world of the imagination on to the stage’ (Chamberlain 2010, 69).

That Lindsay is indeed thinking about what he is doing, has carefully planned it and is not improvising spontaneously is confirmed firstly by his account of how ‘there’s always this ‘stuff’ that I put in’ (2009, 177) for his roles. It is further shown by a slip in his performance with the final near-knock as well as the eventual actual knock at the end of the scene, when his twitch has him bang the door open: in these two instants, his response to the twitch pre-empts the movement of his arm by a fraction. With his actions for the scene evidently planned out and choreographed, he is visibly not genuinely in the moment (and in the first instant very likely to be thinking about the imminent demands of the rest of the scene). Of course, what these tiny slips vividly demonstrate is the overall acting skill of Lindsay and how much he manages to make himself look like he is in the moment, when actually he is not.

A brief moment where the loss of control is visibly controlled

In order to be able to tackle a role and performance so technical, intricate and demanding, RADA-trained Robert Lindsay uses a rich approach to acting that draws on Stanislasvkian and Chekovian approaches, employing physicality and imagination, a high degree of ability, control and thinking through, underpinned by careful rehearsal. Tise Vahimagi in Screenonline rightly praises Lindsay’s work in G.B.H., noting that: ‘He played with all the stops out, creating an extraordinary, unrealistic, chimerical figure as Michael Murray; prancing, twitching, anarchic and unrepressed.’ Interestingly, there is a divergence in point of view between the practitioner’s explicit intention to ‘make it as real as possible’ and the scholar’s reading of the performance as ‘unrealistic’. We share Vahimagi’s view that G.B.H. ‘may well have been Lindsay at his television finest’, but find some of his terminology ill-chosen, for Linday’s Michael Murray strikes us as far from ‘unrepressed’ or indeed ‘unrealistic’: while Lindsay is unrepressed in the sense that he fully commits to the role (which could not have been successfully realized with anything less than that), his acting invests into creating a character who represses both his memory and physicality. More importantly, he does manage to root the outer characteristics in a believable sense of character, taking realism and naturalism up to the line where they border on something else, but without going beyond that point. (Even with the character on the edge of a nervous breakdown, such as Murray, if the actor took it much further than Lindsay does, it would go too far.) The term ‘heightened naturalism’ to us would capture the tone and texture of Lindsay’s performance better.

The courage that a role such as Michael Murray demands of an actor is considerable. That it was taken on by an actor who had lost confidence is remarkable: consider the bravery that it takes to do a scene such as this – alone in front of camera and crew, in a small space and in one take, to attempt something so complicated and judge how far to take it – this scene is about acting. The loss of control, performance anxiety and self-consciousness of the character are performed with aplomb by an actor in control of the material, and as committed as he is un-self-conscious; producing fine acting by a performer who knows he is delivering strong work, which only adds to our enjoyment of the scene. Robert Lindsay puts the cathartic importance of Michael Murray to his career as follows: ‘But GBH gave me that self-esteem back – it proved to me that I could still act.’ (2009, 205) Indeed, he could.

Gary Cassidy is currently undertaking AHRC-funded doctoral research at the University of Reading. His thesis explores the rehearsal process of playwright Anthony Neilson, using filmed footage of rehearsals and interviews. He trained as an actor at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama and has thirteen years of acting experience – Equity name Cas Harkins – covering film, theatre, television and radio. Plans for future research focus on using his research methodology to explore the working processes of other contemporary theatre practitioners.

Simone Knox is Lecturer in Film and Television at the University of Reading. Her research interests include the transnationalisation of film and television (including audio-visual translation), aesthetics and medium specificity (including convergence culture), and representations of the body. She sits on the board of editors for Critical Studies in Television and her publications include essays in Film Criticism, Journal of Popular Film and Television and New Review of Film and Television Studies.

[i] This was an especially interesting challenge for an actor who, because of his ‘‘big face’ and ‘big eyes’’ (Lindsay 2009, 139), has had to ‘work hard at being less expressive in front of the camera.’ (ibid.).