There is a lot of talk about mental well-being at the moment, and it’s great to see that we also contribute to this, not least Kerr Castle in his recent blog, based on his PhD, on comfort television. I saw Kerr present last year at the Critical Studies in Television conference, and it really triggered something in me – suggesting that this is something I at once recognised and felt I needed to think more about. His material on grief and television, I think, in particular struck me as I have found myself eagerly watching TV shows that my mother, who passed away a few years ago, used to watch even though I always found them cheesy and problematic.

The reason why I am talking about comfort TV today, though, is because I recently had an interesting experience, which indicated that there is, for me, as a woman and feminist, another layer at the moment which is really interesting and complex. In part, this was triggered by editing a fantastic article by Kathrine Byrne and Julie Taddeo (forthcoming in the next issue of the journal) on rape narratives in period drama in the #MeToo era, and by a flippant tweet on watching Shetland (BBC, since 2013) as comfort television which resulted in a response by Derek Johnston which made me pause and think:

My first reaction was – oh, he is so right, and I know he is right, because there has been so much written about this by feminists (including a fascinating special issue of Television and New Media which looked at the complexity of these depictions in relation to female empowerment). But then came the question: why then do I find watching Shetland so comforting? Am I a bad feminist? Because unlike the examples discussed in the special issue that Lisa Coulthard et al edited, here we do not have a female detective, but a male one. In addition, unlike many of the other male detectives, particularly (but not just) in the Nordic Noir tradition, Jimmy Perez (Douglas Henshaw) is pretty awesome all way round: he grieves his wife, he is a better (adoptive) father to his daughter than her biological father with whom he nevertheless manages to be good friends and he is a supportive colleague and friend. So, we have here a really positive representation of masculinity that at the same time is also closely connected to traditional bastions of patriarchy. One could even argue he presents a positive representation of a quite hegemonic masculinity (although there is a woman, Rhona Kelly played by Julia Graham, with more authority raining him in). For me who has studied representations of hegemonic masculinities and the problems they cause, the thought of potentially finding comfort in this hegemonic masculinity that in traditional patriarchal ways makes sure we are all safe is intellectually deeply troubling. But the fact is I do. I find watching Shetland relaxing. Incredibly relaxing.

There are a number of reasons for it, not least because the programme engages with contemporary issues in ways that can only be considered moralistic. Like other crime drama, it ponders what our reactions should be in particular moments and how we should behave. There are also the many exceptional guest performances, not least this season by Rakie Ayola (who played Olivia, the victim’s mother). However, the main reason is because Douglas Henshaw is a fantastic actor. Gary Cassidy and Simone Knox highlight how important it is to pay attention to the skills actors bring to the production. In particular they indicate, drawing on Barker (1977), how a good actor ‘brings to his performance a deep sub-textual understanding of the inner life of the character’, and Henshaw excels at this. His face communicates every moment of feeling, and many of the emotions communicated are those of compassion. To put it simply: his Jimmy Perez cares. The image below shows the depth of his grief when seeing a murder victim for the first time which is nicely counterpoised by the two other detectives, Alison McIntosh, or Tosh (played by Alison O’Donnell) and Sandy Wilson (Steven Robertson) who are busy with organisational issues and have either their body or their head turned towards each other, rather than towards the victim from whose point of view the image is shot.

Thus, although by series 6 you would think he has gotten used to seeing death, Jimmy Perez grieves every death as if it is a first and as if it was personal. Of course, these are well-established tropes in crime drama and fiction, again, however, more widely found in drama based on female investigators. And in this respect, perhaps, this isn’t so hegemonic a masculinity. There are two ways of reading this: we can read this as an attempt of subversion by creating a non-hegemonic masculinity within traditional bastions of patriarchy (in this respect the fact that he is called Perez and that he is an adoptive rather than biological father are important), or we can read this as an attempt to re-instate hegemonic masculinity as benevolent at a time when much of our effort is placed on criticising traditional masculinities. I am of course, likely to read it in the first way, but I am fully aware of this contradiction. It is the fact that the latter interpretation exists that is troubling the feminist. And yet Shetland is comforting, right now, when I am tired out from marking at the end of the academic year.

So, why do I find a patriarchal detective who cares so comforting? There is a very simple answer to this. Look around you. I don’t want to re-traumatise you, but there are currently several faces that come to mind that remind me of the continued power (and popularity) of hegemonic, and even toxic masculinities. I have chosen to use satire representations, to lessen the impact, but here they are:

Fig. 3: US President Donald Trump (Alec Baldwin) on Saturday Night Live. Source: YouTube

Fig. 4.: Boris Johnson (Drew Galdron) in Being Boris. Source: YouTube

Fig. 5: Jacob Rees Mogg (Liam Hourican) in Tracey Breaks the News. Source: YoutTube

Fig. 6: Nigel Farage (Kevin Bishop) in Nigel Farage Gets his Life Back. Source: YouTube

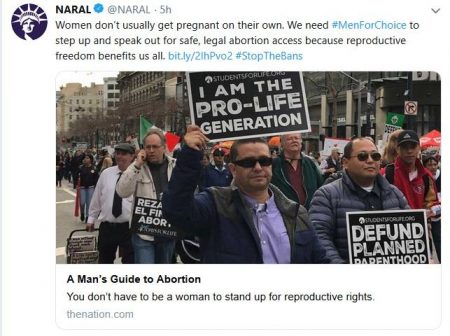

And because too many of them have too much power, they have also created a particular environment in which the debates we thought we had started as public debates have been returned to the domain of women. Thus, at the beginning, #MeToo felt like a global movement that highlighted the systemic nature of sexual violence in the oppression of women. And because it was so global, men and patriarchal systems responded to that by admitting the problem and perhaps adjusting some of the issues. But now, as so often in response to a feminist movement, a backlash is scaling these advances back. We are seeing the continuous attack on women’s rights, including their right over their own bodies, the continuation of court cases where women are disbelieved, and the sense that basically it is all our work that needs to be done in order to prove that things aren’t right at the moment. Well-meaning advice in the fight against overpopulation that we need to educate first of all girls do nothing but to emphasise the power imbalance: it is all women’s work and responsibility. That #MeToo made clear that having children isn’t always our ‘choice’, but can be part of the oppressive system of gendered violence falls on deaf ears, it seems. That the burden of responsibility is constantly shifted onto women is made even more evident by the fact that it is currently also mostly women who do the other work to highlight the problems of the systemic failure of politics. And in that respect, these inspiring women come to mind:

When you have to juggle a job that is emotionally and physically draining, particularly at a time of a crisis in well-being of both students and staff, and you still have to carry most of the mental load at home as well, then the last thing you need are men like the ones above. Instead, what you need is to go home and switch the telly on and find a man in a position of authority who cares and who tells you that he does, and that he will make it alright. Yes, that – being able to give up responsibility for an hour to a man who cares – is relaxing.

Elke Weissmann is Reader in Film and Television at Edge Hill University. She is currently considering changing this to Reader in Television and Film, however. Her books include Transnational Television Drama (Palgrave) and the edited collection Renewing Feminisms (I.B.Tauris) with Helen Thornham. She sits on the board of editors for Critical Studies in Television. She migrated to the UK in 2002 after realising that German television was as bad as she remembered.