Many years ago – although possibly not as many as that – I did used to do quite a bit of artwork. Mainly pencil sketching and the odd bit of pointillism with black ink pens… if a piece needed to be published. Not much in colour though. Never very good at that. Possibly when it came to inks and paints I was always a bit too impatient… and the pigments ran and merged and mixed and blended. And blending was something I could never quite predict.

Colour blending didn’t seem to have the mathematical precision that I needed. Pointillism was nicely binary – black and white, on and off, 1s and 0s. I mean, I’d been given a fairly basic understanding of colour blending by Angela Banner and her very close associates Ant and Bee fairly early on in life – probably around Freshers’ Week. Add blue to red for purple. Red and yellow gave orange. Yellow + Blue = Green. Maths – yes – I can see it more easily when we convert it to maths. And there’s a nice consistency to it which I can understand.

Anyroadup… Television. Yes, that’s what we’re really all here for. And, thus far, I’ve enjoyed some cracking television in 2021. And some of the best of all has been the brand-new episodes of the gritty counter-espionage series Callan (1967-1972), which, as you’ll see from the start and end dates in the brackets hasn’t actually offered any new episodes in almost 50 years now. Unless we’re counting the 1981 revival play Wet Job … which I try not to.

Created by South Shields writer James Mitchell, Callan originated almost as a television version of the cinematic delight The IPCRESS File – a down-at-heel, dour, take on the spy business which was as much a counterpoint to the gloss of James Bond on the big screen as the increasingly bizarre antics of John Steed and his friends – alias The Avengers (1961-1969) – were on the small. Callan himself was a working-class man trapped in a terrible but vital job – a former soldier with a talent for using a gun which, blended with his training from a locksmith, offered a cocktail which made him the perfect undercover executioner for a shady sector of British security known as the Section, presided over by a series of officer-class figures referred to as Hunter.

Luckily for the viewer, Callan was blessed with a conscience. And this gave rise to many of the very best scripts for the series where the licensed hitman formed his own sense of justice concerning those he had been sent to observe and possibly eliminate. The drama arose from these conflicts.

So, where have I located these fresh assignments of this rather antiquated branding? Netflix? Nah – can’t afford that. YouTube? What… go to all that hassle of getting HDMI cables and wiring up laptops to television sets? No… Callan is old school, so it seems rather fitting that his latest assignments arrive with me in an old school format. This latest batch of Callan files arrive through the post on four shiny discs. Pop them in the CD player and I’m good to go…

No – sorry. Not the DVD player. The CD player will do me. Just sound – no pictures.

The quartet of cases that I’ve just heard Hunter allot to Callan have been audio plays, brilliantly crafted by a team with an excellent understanding of how and why the original television series worked – and thus capable of crafting what, for me, is superb television, despite the fact that it clearly isn’t television. They’re made by a company called Big Finish, a publisher that in recent years has revived all manner of defunct TV titles embracing the social satires of Adam Adamant Lives! (1966-1967), the galactic odyssey of Space: 1999 (1975-1977) and filling in gaps from the archival omissions of the aforementioned The Avengers.

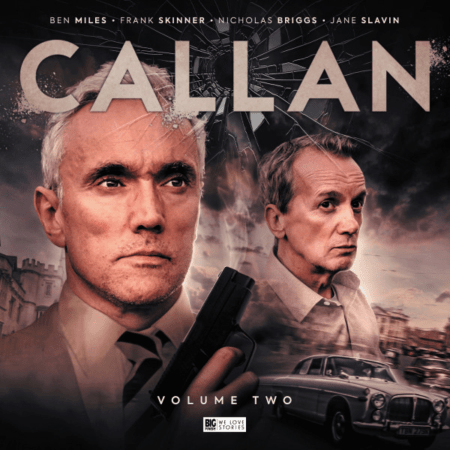

There is a great care taken with the presentation to get the ‘sense’ of Callan correct. Callan himself is now played by Ben Miles – of Coupling (2000-2004) and The Crown (2016-) – in a manner that captures the spirit of the original performance of Edward Woodward from the TV version. The chip on the shoulder is still there, along with the class distrust of his superiors. When a break-in is necessitated for a vital piece of evidence, Callan calls upon an odoriferous acquaintance known as Lonely, a petty and pathetic London burglar originally embodied as Glaswegian actor Russell Hunter and now reincarnated by West Bromwich comedian Frank Skinner. Neither of these leads offers a direct impersonation – yet the characters are immediately and potently the same as they were all those years ago. Add to this Nicholas Briggs as a generic but pleasingly effective Hunter who embodies elements reminiscent of the William Squire and Ronald Radd incarnations.

Fig. 2: Order yours now, while stocks last!

This latest set of compact discs has been directed by Samuel Clemens in a style which I find absolutely perfect and which I’m probably about to attempt to compliment with something that sounds rather derogatory. They have the sense of being classic editions of Radio 4’s Saturday Night Theatre from the 1970s. There, I’ve said it. Sorry if that’s not quite cutting edge enough in terms of sound design… but it’s precisely what I’m after if I’m going to sit down and listen to Callan. It’s a choice of approach totally in sympathy with the subject matter – very smart to my mind.

But without the pictures, why do I accept this Callan as being brilliant television. Possibly because, for many years, television for me wasn’t just about the pictures. From around 1975, if I wanted to preserve a particularly good television programme to enjoy again and again at my own convenience, I was pretty much limited to the modern marvel of the compact audio cassette. C60s and C90s filled the shelves as I built up my little archive of radio shows and television soundtracks, waiting for the day when I could embrace the cutting-edge tech of a Sony Betamax SL-C5 so that chunkier tapes would fuse sound and vision. But 195 minutes of recording time on an L-750 tape was still expensive, particularly for one starting a working life in engineering and entering tertiary education…

… which is why through to 1985 I couldn’t keep everything that I wanted to on videotape. Hence various examples of the repeats of Callan lavished upon me by a benevolent Channel 4 during 1984 were preserved on audio cassette. I got used to listening to these sound-only versions… often while sketching a portrait for a friend or picking out some pointillism for a publication.

And these CDs are just like that. I even find myself listening to a scene where Callan’s narrative has taken him outside and thinking “Ahhh – that bit would be done on Outside Broadcast around Teddington” or “Oh, I bet they’d have sprung for a full 16mm film crew for that sequence”.

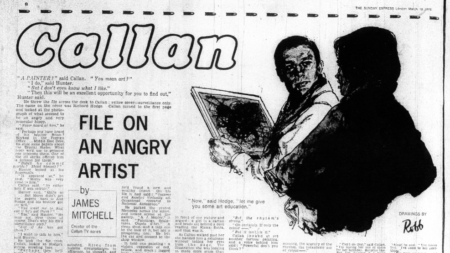

But here’s the really weird bit. These sound-only stories aren’t even TV scripts of the missing episodes. They’re actually adaptations of short stories which James Mitchell penned for the Sunday Express between 1970 and 1976. Even more amazingly, these short stories weren’t actually that good. No – I don’t mean that they were poor prose or ill-conceived. They were fine. I just mean that, squeezed into two pages along with advertising space and dynamic illustrations by Robb, they didn’t have the space to breathe – to become the involved assignments that Callan found himself entwined in on television. They lacked the depth accorded by the TV scripts – and also the excellent novels that James Mitchell penned as he increasingly nudged the style of his creation away from its small-screen form into something more expansive and exotic.

Fig. 3: “Come off it Hunter,” said Callan, “I’ll need more than two pages if I’m going to do this job properly like I do on television.”

So, here’s the real genius. These short stories now make perfect episodes of Callan. They have been adapted by Peter Mitchell, James’ son and a former director of programmes at Tyne Tees television. And these are precision engineered versions of the weekend spreads, expertly expanded into fresh files which feel and sound exactly like Callan did in the 1960s and 1970s with everybody using pre-decimal coinage and limiting their language to a handful of ‘bastards’ in the days before drama gave characters the freedom to ‘hump that’ and ‘hump you’ and humping hump everything.

Hunter now gives Callan each new assignment which is played out in the classic three-act structure of the original episodes – investigation, complication, resolution – and each book-ended with the signature tune of Girl in the Dark, the brooding piece of library music created in 1966 by Dutch composer Jan Stoeckhart under his pseudonym Jack Trombey. Just the way that it sounded when I listened back to my C60s, each recorded with the commercial breaks carefully removed but the bursts of Girl in the Dark either side of them intact. Peter Mitchell’s rhythm of presentation is pitch perfect in pacing.

Thus a short story that didn’t quite work on the printed page transferred to the medium of radio makes perfect television. In fact, some of the best television I’ve enjoyed this year… including real actual television. Instinctively, that doesn’t sound right to me – and probably not to you either. It’s that blending again. Having just learnt from Ant and Bee that Blue and Yellow gave Green, along came trade test films for colour television on BBC-2 which contradicted the educational insects by assuring me that Red and Green actually gave Yellow.

So, all these years later, it looks like I’m still learning new, surprising equations about blending. The latest being that Prose + Radio = Television.

Andrew Pixley is a retired data developer. For the last 30 years he’s written about almost anything to do with television if people will pay him – and occasionally when they won’t. And, again, he’s failed to use the word barquentine. Maybe he’ll get it in next time?

Can I post a URL here?

cstonline.net//cstonline.net///work-in-progress-by-andrew-pixley/

Ahhh… so I can post the address… but *not* the URL itself.

Interesting…

Okay – you can ignore this. This is just me having a play.

Andrew