‘Say what you like about South London, but it pays all our wages’

Edwyn Cooper (ep.1)

Some years ago, I immersed myself in British tales of armed robbery – blags – while researching a study of the four-part BBC series Law and Order (1978) which is based on events surrounding a wages grab in South London. Law and Order was formally innovatory in structure, with narrative repetitions from different viewpoints, while at the same time looking like a dirty realist version of The Sweeney (1975-8 ITV), the hit Flying Squad police drama of the period. Its proposal of systemic corruption within the criminal justice system was greeted with outrage at the time, but has subsequently been proved substantially correct. Since then, I’ve kept an eye on armed robbery in British film and television, which is not difficult to do as there’s a lot of affection for the blag in British media culture; the BBC’s 2023 hit, The Gold, is its latest manifestation (fig. 1).

You don’t need to have immersed yourself in the particularities of the British context to be familiar with the key elements and rules of the heist drama. There’s usually a before – planning, identifying the target, building the team, getting the equipment. There’s the raid itself, which may require skill, endurance and brutality. Then there’s the aftermath, with sometimes a chase, sometimes a falling out among thieves. There is investigation, pursuit, fencing or concealing the loot, and whatever happens next. The interest in looking across different examples of the genre in a particular national context lies in the way in which different versions of this old story accentuate different processes, characters, institutions and causalities. Who’s robbing whom, or what, and how does the drama set up the project and its context? The Gold is self-conscious about its generic heritage, and distinctive in articulating a two-faceted anti-establishment drive for both the villains and the investigating police. Banal though some of the expressions of this drive are, some emphases are worth teasing out. The show is knowing about its 1980s setting, and its writer, Neil Forsyth, identified its themes as ‘greed, class and corruption’. However, I wonder whether this drama set in the volatile Britain of high Thatcherism might end up being a little more Thatcherite than intended.

The Gold is a six-part drama ‘inspired by real events’ following the 1983 Brink’s Mat gold bullion robbery from a depot near Heathrow Airport. Its governing conceit, given its final expression by one of the accused in the trial scene of the concluding episode, is the rendering of autonomy to gold so that the gold itself becomes an animating force in the narrative. As John Palmer (Tom Cullen), the smelter, puts it, ‘The thing about gold is that it’s not yours, not really, you’re just looking after it and then you die and it passes on.’ The magical qualities of gold are emphasised throughout, from the very first, withheld glimpse of the bullion bars in the warehouse, when we are shown only the widening, and then smiling, eyes of a balaclava’d Mickey McAvoy (Adam Nagaitis) as he recognises what lies before him, to the long-held money shot of the smelting of the first bar, the molten heat of the furnace filling the screen. This characterisation of gold enables the drama to deal with the ways in which the stolen bullion is transformed: smelted down (fig 2), sold on, turned into cash, used to buy property, deposited in swiss bank accounts and reintroduced to the market in many modalities. etc. As the opening titles declare, ‘If you have bought gold jewellery in Britain since 1984, it is likely to contain traces of the Brink’s Mat gold’. The animation of the gold permits the drama to literally follow the money, suggesting a reweighting of bank-job dramas so that it is what happens to the gold, and who is involved in these transformations, which is of most interest.

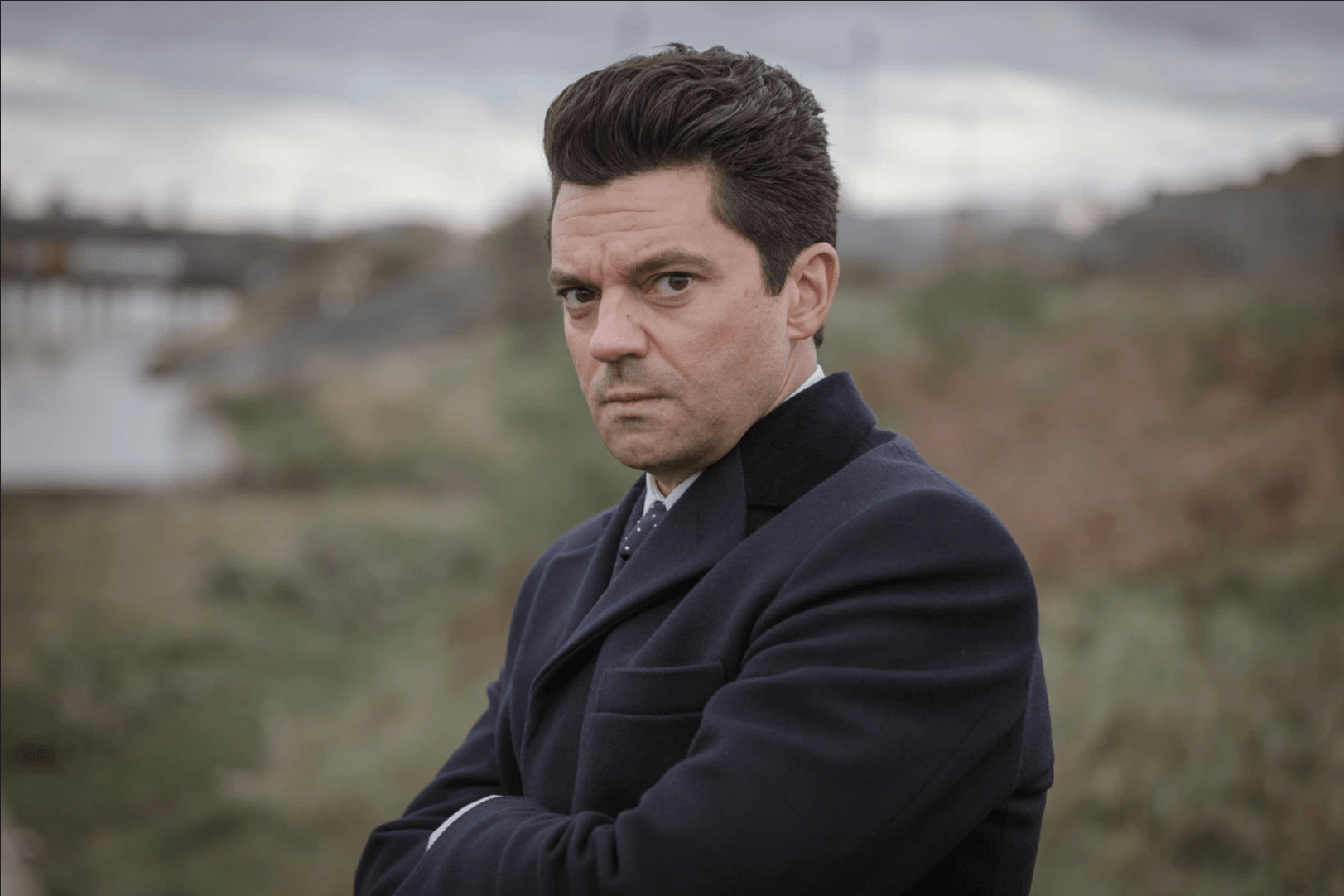

The Gold was a success when it was broadcast in spring 2023 and has been one of the BBC’s recent shows which has broken through the schedules to reach viewers accustomed to stream their choices – a significant objective for the Corporation. It joins a medley of heist films and television programmes which in Britain tend to be set in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s (when wages were paid in cash) – the peak period for armed robbery. The Gold revisits this territory with a certain retro panache in its use of costume, cars and production design. It’s set in the past, but it’s a recognisable version of the early 1980s–the modern past, with some quite zingy colours, as opposed to the dull colour palette of the contemporary Law and Order, which could, in contrast, be characterised as the old – dreary – past. And in this modern – vintage – past, there are more women playing significant roles, and some key characters are given psychic interiority. Terrible childhoods haunt the smelter John Palmer and the solicitor Edwyn Cooper (Dominic Cooper), while the old-fashioned integrity of DCI Boyce (Hugh Bonneville) is shaped by experiences of war in Cyprus (and, it must be said, the long shadow of Downton Abbey (2010-15)). Self-consciousness about genre is partly marked through characters who are themselves self-conscious.

But the modernity of The Gold is manifest in other ways too. Scenes are intercut briskly, and viewers are expected to be generically sophisticated, understanding, for example, the mobility of the gold through different accomplices in the montage at the opening of the second episode. In terms of the depicted world, the show conveys something of the pleasures that mass tourism brought to those previously excluded from foreign travel. As Kathleen Meacock (McAvoy’s mistress/ Sophia La Porta) declares passionately in the first episode, the gold provides a means of escape for them from their origins, the possibility of living the rest of their lives ‘with the sun on their faces’. The gold is both motive and metaphor, a way of effecting, and tracking social change. As characters keep saying to each other,‘this country is changing’.

The most significant invented character in the drama, the very sign of its attractive retro past, is the red-headed D.I Nicki Jennings (fig 3). This character, in a fine performance by Charlotte Spencer, does two things for the drama. She is the embodiment of the modernity of show – an intelligent, determined and articulate detective who can, if necessary, scrub up well and accompany her boss to a London club. She is also though a child of a well-known criminal and thus of one of the key – and strongly mythologised – locations for the series, south London. South London here is less a particular location – although it is that, and the script offers some sharp repartee on remembered childhoods – than a state of mind, a community of criminality. The dilemma for the South London gang that actually stole the gold is that they must deal with people outside South London to successfully dispose of it.

Counter to South London, but also, it transpires, accessible from it, is the other key term of the drama, the hidden hand of the Masonic Brotherhood. It is through the reach of the Masons that the corruption of the British establishment is figured, and DCI Boyce and his trusty team must evade the Masons in the police as much as they pursue the gold. Boyce’s class origins have evidently impeded his promotion in the army, and he thus joins the rest of the central characters – most of them on the other side of the law – in his consciousness of a Britain rigidly class-stratified and hostile to class mobility. Class consciousness pervades the drama, from the aspirations of Noye and Palmer to vault over those above them, to the concealed origins of the crooked solicitor who is humiliated by his father-in-law for a ‘brash’ taste for New World wines, to DC Nicki Jennings’ statement that ‘I don’t think we should only nick people who talk like me’. The key characters in this drama are all individuals who find themselves excluded from patterns of power in ‘this country’, but who are close enough to see these patterns and sense the possibility of change.

The Gold is connected to, but does not quite fit, the long tradition of affection for the ‘lovable rogue’ in British culture. Its project is more ambitious than rehearsing the hearts of gold of notorious gangsters, and is carried in the title. The gold itself is both present and absent in the drama. Through Palmer, in particular, the character who ‘knows gold’, it is viscerally present, in both the labour of the smelting and of the consequent money laundering: ‘It’s like a poison passing through us’. This labour is, precisely, to make the gold disappear. It will be transformed into the materiality and profit of the 1980s. A couple of years before the deregulation of the City of London, Forsyth has identified the Brink’s-Mat money laundering story, and its link to the redevelopment of the London Docks, as precursor to the new roles of the financial services industry in London (fig 4).

Armed robbery in this story is a re-distributive project (which indeed it is), but here given a populist, and even Thatcherite, edge. It is not just that Brink’s-Mat money is used to make initial purchases of the abandoned wharves that will later become Docklands, the quintessential Thatcherite project. The class consciousness that provides a constant thrum throughout the drama is a class consciousness quite distinct from the notions of class solidarity which shaped the phrases in which it is articulated, and finds no other possible outlet than personal advancement and gain. The motivating class-resentment of those involved in the gold-laundering, their profound distrust of the Establishment, and the revealed corruption of that establishment, is countered only by Boyce’s trusty band of non-Masonic detectives who struggle to maintain law and order across all sectors of society. Despite Boyce’s rousing final speech about excellent detection, and the listing of the prison terms of those convicted, one doesn’t quite feel that Boyce’s crew wins. Instead, just as Thatcher herself was subject to considerable snobbery from those from more established class positions, The Gold presents its viewers with a Thatcherite alliance in which the movers and shakers are those who will disrupt established patterns of power, assimilating themselves into an already corrupt establishment and making lots of money in the process.

The Gold is available at BBC iPlayer, and on Paramount+ in the US.

Charlotte Brunsdon is author of Television Cities: Paris, London, Baltimore (Duke 2018), Law and Order (BFI 2011) and London in Cinema (BFI 2007). She has recently edited a selection of Stuart Hall’s media essays, A History of the Present (Duke 2021) and is Professor Emeritus of Film and Television Studies at the University of Warwick.