Spying on Spies was an international conference held in London over 3-5 September 2015, organised collaboratively by myself and Toby Manning (Open University). The aim was to bring together a diverse array of international research on the spy thriller, one of the defining popular genres of the 20th and early 21st centuries which has provided an alternative lens onto broader cultural and geopolitical shifts over the this time. Over the three days scholars examined representations of espionage from around the world and across different media, including literature, film, theatre, comics, computer games and even poetry. It was held in the Warwick Business School space within the Shard, an extremely exciting and appropriate venue for such an event, combining the spectacular and evocative views of the London skyline that you might find in Spooks (2002-11) or Skyfall (2012) with slick interior design and technological modernity reminiscent of any number of modern surveillance thrillers.

Included amongst this diverse research was a range of rich and fascinating papers focusing on the representation of espionage in television dramas. Here I will provide an overview of these papers to illuminate this part of an exciting new generic research community. Firstly I should note that my discussion below does not follow the order in which the papers were presented at the conference, where all of them were situated in interdisciplinary panels arranged around very different thematic connections. The following is instead a retrospective account which I have structured around some interesting discursive patterns that I think might be most interesting to scholars of television.

Included amongst this diverse research was a range of rich and fascinating papers focusing on the representation of espionage in television dramas. Here I will provide an overview of these papers to illuminate this part of an exciting new generic research community. Firstly I should note that my discussion below does not follow the order in which the papers were presented at the conference, where all of them were situated in interdisciplinary panels arranged around very different thematic connections. The following is instead a retrospective account which I have structured around some interesting discursive patterns that I think might be most interesting to scholars of television.

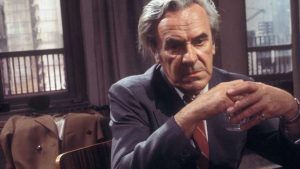

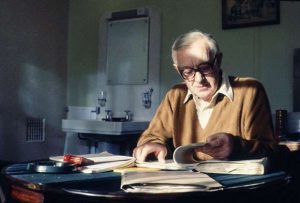

The majority of the historical analysis on television dramas was focused upon British programmes, perhaps unsurprisingly given both the UK’s prolific output of spy dramas in previous decades, and also the location of the conference. Yet interestingly, the 1960s adventure series which have dominated past accounts were here somewhat marginalised by an alternative focus on a rather different strand of ‘prestige’ drama. Tom May (Opening Negotiations: British Culture in the Cold War blog) provided an in-depth analysis of Traitor (1971), a BBC 1 Play for Today written by Dennis Potter about a Kim Philby-type agent in exile in Moscow, examining its portrayal of treachery and national identity. In another panel, my own paper took this play as a starting point for a more longitudinal examination of allegorical and biographical portrayals of Philby on television, extending the analysis onto Ian Curteis’ docudrama Philby, Burgess and MacLean (ITV, 1977) and the BBC 2 classic serial adaptation of John Le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Solider Spy (1979). Here I explored a transition from tense studio-bound psychological dramas of interrogation to more elegiac pieces shot largely on location amidst rural scenery and elite cultural spaces.

The majority of the historical analysis on television dramas was focused upon British programmes, perhaps unsurprisingly given both the UK’s prolific output of spy dramas in previous decades, and also the location of the conference. Yet interestingly, the 1960s adventure series which have dominated past accounts were here somewhat marginalised by an alternative focus on a rather different strand of ‘prestige’ drama. Tom May (Opening Negotiations: British Culture in the Cold War blog) provided an in-depth analysis of Traitor (1971), a BBC 1 Play for Today written by Dennis Potter about a Kim Philby-type agent in exile in Moscow, examining its portrayal of treachery and national identity. In another panel, my own paper took this play as a starting point for a more longitudinal examination of allegorical and biographical portrayals of Philby on television, extending the analysis onto Ian Curteis’ docudrama Philby, Burgess and MacLean (ITV, 1977) and the BBC 2 classic serial adaptation of John Le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Solider Spy (1979). Here I explored a transition from tense studio-bound psychological dramas of interrogation to more elegiac pieces shot largely on location amidst rural scenery and elite cultural spaces.

Indeed, after years of being regularly acclaimed as one of the greatest dramas in the history of British television, Tinker Tailor seems to be somewhat belatedly attracting significant academic attention, perhaps in part spurred on by the recent film adaptation (Tomas Alfredson, 2011). Douglas McNaughton (University of Brighton) compared the two versions in order to problematise the assumption that television drama of the 1970s was predominantly ‘theatrical’ in form, considering the 1979 adaptation’s pioneering status as an early all-on-film serial for the BBC. Our third keynote speaker Rosie White (Northumbria University) also incorporated some analysis of Tinker Tailor in her analysis of the representation older woman spies in fact and fiction and the queer potential in such portrayals. Here Le Carré’s Connie Sachs was situated alongside real-life Soviet spy Melita Norwood and Dorothy Gilman’s Mrs Pollifax novels, and this discussion was vividly illustrated with an analysis of Beryl Reid’s performance as Connie in the 1979 adaptation (see clip).

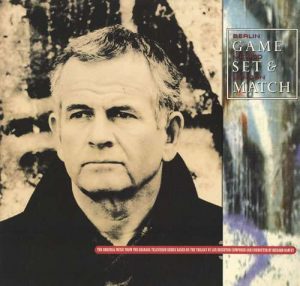

Alan Burton (Klagenfurt University), meanwhile, looked at a much less-well-known spy adaptation, Granada Television’s lavish 13-part Game, Set and Match (1988) based on three novels by renowned spy author Len Deighton. He described how this was Granada’s attempt to produce a ‘prestige’ serial in the mould of the BBC’s Le Carré adaptations, yet after suffering a poor critical response it has been largely forgotten and indeed actively suppressed by Deighton himself

Alan Burton (Klagenfurt University), meanwhile, looked at a much less-well-known spy adaptation, Granada Television’s lavish 13-part Game, Set and Match (1988) based on three novels by renowned spy author Len Deighton. He described how this was Granada’s attempt to produce a ‘prestige’ serial in the mould of the BBC’s Le Carré adaptations, yet after suffering a poor critical response it has been largely forgotten and indeed actively suppressed by Deighton himself

One of the most fascinating opportunities presented by an international conference such as this was the possibility of contrasting Cold War culture on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Two papers examined the long-running East German spy series Das unsichtbare Visier (The Invisible Visitor, 1973-79), which depicted missions by a James Bond-style agent of the Stasi into a version of West Germany as imagined by the GDR. This thereby provided a fascinating reversal of the typical perspective of Western Cold War fiction. One of our plenary speakers, Patrick Major (University of Reading), examined the difficulties the GDR had in engaging with what was considered a petit bourgeois genre and the strategies by which they worked to avoid glamorising the West, which posed a particular problem when its leading actor, Armin Mueller-Stahl, emigrated to West Germany. Sebastian Haller (Danube University) situated the series in a drive by state-led television to embrace entertainment values and promote a Socialist Popular Culture, combining Bond-style conventions with the political culture of the time and creating an image of Western nations as being ruled by neo-fascists, imperialists and militarists.

One of the most fascinating opportunities presented by an international conference such as this was the possibility of contrasting Cold War culture on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Two papers examined the long-running East German spy series Das unsichtbare Visier (The Invisible Visitor, 1973-79), which depicted missions by a James Bond-style agent of the Stasi into a version of West Germany as imagined by the GDR. This thereby provided a fascinating reversal of the typical perspective of Western Cold War fiction. One of our plenary speakers, Patrick Major (University of Reading), examined the difficulties the GDR had in engaging with what was considered a petit bourgeois genre and the strategies by which they worked to avoid glamorising the West, which posed a particular problem when its leading actor, Armin Mueller-Stahl, emigrated to West Germany. Sebastian Haller (Danube University) situated the series in a drive by state-led television to embrace entertainment values and promote a Socialist Popular Culture, combining Bond-style conventions with the political culture of the time and creating an image of Western nations as being ruled by neo-fascists, imperialists and militarists.

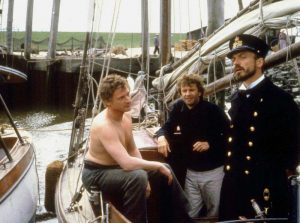

Whilst these papers consider how how the values of spy thrillers were translated between political cultures, an analysis of a later West German series by Joseph Willis (University of Tulsa) provided an opportunity to examine how such values were translated historical contexts. Rainer Boldt’s Das Rätsel der Sandbank (1985) was a serialised adaptation of Erskine Childers’ formative British spy novel The Riddle of the Sands (1903), and Willis’ paper explored how anxiety concerning the naval arms build-up between England and Germany prior to the First World War resonated in the context of the 1980s nuclear arms race between the USA and the USSR.

Whilst these papers consider how how the values of spy thrillers were translated between political cultures, an analysis of a later West German series by Joseph Willis (University of Tulsa) provided an opportunity to examine how such values were translated historical contexts. Rainer Boldt’s Das Rätsel der Sandbank (1985) was a serialised adaptation of Erskine Childers’ formative British spy novel The Riddle of the Sands (1903), and Willis’ paper explored how anxiety concerning the naval arms build-up between England and Germany prior to the First World War resonated in the context of the 1980s nuclear arms race between the USA and the USSR.

In contrast to the British and German focus of most historical analysis at the conference, studies of contemporary television texts tended to be concentrated on American series. Much of this was focused on new moral uncertainties; for example, Pablo I. Castrillo (Universidad de Navarra) argued that 9/11 film and television had seen increasing hybridisation between the spy and political thrillers. In series such as Homeland (2011-), Person Of Interest (2011-) and The Americans (2013-) (as well as numerous films examples), darker traits of the political thriller such as alienation, moral ambiguity and pervasive corruption, has created a pessimistic vision of espionage that in some ways harkens back to the height of Cold War paranoia. Aleid Fokkema (Erasmus University Rotterdam) explored the uncertainties around identifying the enemy in Homeland, arguing that by overturning expectations it precludes a homogenised and neatly ‘othered’ enemy, and that this is countered by a more intimate and intuitive form of information-gathering.

Indeed, how technological developments have impacted upon intelligence practice was another recurrent theme. Patricia Trapero Llobera (University of the Balearic Islands) examined the depiction of state surveillance in Person of Interest, considering the series as an example of neo-baroque storytelling combining the plotlines of crime fiction plotlines and the premisis of dystopian-cyberpunk, drawing upon cultural materials such as films and comic books. Rob Coley (University of Lincoln) examined Homeland and Legends (2014-) as expressions of ‘accelerationist’ tendencies in contemporary political culture, with the former in particular creating a paranoiac and schizophrenic vision of national security in which CIA analyst Carrie Mathison’s powers of intuition complicates the intellectual rationality of conventional tradecraft.

Finally, Harriette Kevill-Davies (Northwestern University) examined The Americans, a contemporary reimagining of the Cold War in which two Soviet agents operate undercover as an American couple in during the Reagan administration. This scenario provides an unusual perspective from which to explore the moral impact of espionage, and her paper was particularly focused on the male protagonist Philip Jennings in relation to ideals of masculinity and nationality.

Finally, Harriette Kevill-Davies (Northwestern University) examined The Americans, a contemporary reimagining of the Cold War in which two Soviet agents operate undercover as an American couple in during the Reagan administration. This scenario provides an unusual perspective from which to explore the moral impact of espionage, and her paper was particularly focused on the male protagonist Philip Jennings in relation to ideals of masculinity and nationality.

The cumulative effective of these diverse and engaging papers was a fascinating portrait of how the genre has evolved over the last 50 years of television drama, enhanced by the much longer-term view of the global history of the spy thriller in other media provided by the rest of the conference. Yet in that context, it is interesting to note the strong focus on British, German and American texts in analysis of television, compared to the research presented on literature and film which ranged even more widely, examining texts from places such as India, Italy, Russia, Spain and Turkey. Are there traditions of television spy drama elsewhere in the world that went unaddressed at this conference? Is this a reflection of lack of production, lack of availability, or a continuing perception of television’s lower cultural status? This is something that I would certainly be keen to hear more about should the opportunity arise.

It is notable how the last generation of ‘war on terror’ spy series such as Spooks and 24 (2001-10, 2014) seem to have already become yesterday’s news. Also interesting is how, to take this pattern of discourse at face value, one can easily get the impression that high-end spy drama was dominated by British television in the Cold War era and later neatly migrated to the USA in time for the ‘War on Terror’. In the process, British obsessions with cerebral detection, class boundaries and personal betrayal have been supplanted by a more American ‘paranoid style’ rooted in fear of state conspiracy, surveillance and ‘accelerationism’. This of course corresponds to a common wider assumptions about the changing site of ‘quality’ television, but seems like something that could be interrogated in more detail in relation to the specific conventions of the spy genre.

It is notable how the last generation of ‘war on terror’ spy series such as Spooks and 24 (2001-10, 2014) seem to have already become yesterday’s news. Also interesting is how, to take this pattern of discourse at face value, one can easily get the impression that high-end spy drama was dominated by British television in the Cold War era and later neatly migrated to the USA in time for the ‘War on Terror’. In the process, British obsessions with cerebral detection, class boundaries and personal betrayal have been supplanted by a more American ‘paranoid style’ rooted in fear of state conspiracy, surveillance and ‘accelerationism’. This of course corresponds to a common wider assumptions about the changing site of ‘quality’ television, but seems like something that could be interrogated in more detail in relation to the specific conventions of the spy genre.

Certainly, this might explain why the 1979 BBC adaptation of Tinker Tailor Solider Spy has re-emerged as such a key site of interest. As a ‘prestige’ serial with a long-form complex narrative, exported around the world (shown on PBS in the USA), it is perhaps a key (if distant) influence on modern ideas of ‘quality’ television and its intersection with the generic traits of espionage. At the same time, it also provides a benchmark for nostalgic, pre-digital, pre-‘accelerationist’ spy drama.

Certainly, this might explain why the 1979 BBC adaptation of Tinker Tailor Solider Spy has re-emerged as such a key site of interest. As a ‘prestige’ serial with a long-form complex narrative, exported around the world (shown on PBS in the USA), it is perhaps a key (if distant) influence on modern ideas of ‘quality’ television and its intersection with the generic traits of espionage. At the same time, it also provides a benchmark for nostalgic, pre-digital, pre-‘accelerationist’ spy drama.

Yet that this conference can inspire such reflection on gaps in research and potential paths for future exploration stands, I think, as evidence of how inspiring it was. Although I don’t have the scope to expand on all of the papers presented across the various different fields, I’d like to briefly acknowledge the fascinating papers from our other two keynote speakers, Phyllis Lassner (Northwestern University), who looked at women writers of spy fiction, and James Chapman (University of Leicester), author of the key study of 1960s television adventure series Saints and Avengers, who here chronicled the spy films of Alfred Hitchcock.

Yet that this conference can inspire such reflection on gaps in research and potential paths for future exploration stands, I think, as evidence of how inspiring it was. Although I don’t have the scope to expand on all of the papers presented across the various different fields, I’d like to briefly acknowledge the fascinating papers from our other two keynote speakers, Phyllis Lassner (Northwestern University), who looked at women writers of spy fiction, and James Chapman (University of Leicester), author of the key study of 1960s television adventure series Saints and Avengers, who here chronicled the spy films of Alfred Hitchcock.

We would again like to thank everybody who came to the conference for making it such an exciting and engaging three days. We believe that it was highly successful in demonstrating the range and depth of research on the spy genre, and has played a highly productive role in establishing new connections across disciplines and cultural contexts. This will, we hope, be something that can be built upon effectively in the future.

We would again like to thank everybody who came to the conference for making it such an exciting and engaging three days. We believe that it was highly successful in demonstrating the range and depth of research on the spy genre, and has played a highly productive role in establishing new connections across disciplines and cultural contexts. This will, we hope, be something that can be built upon effectively in the future.

Joseph Oldham is an Associate Fellow in Film & Television Studies at the University of Warwick, having been awarded a PhD in 2014. His research interests include the history of British television drama, particularly spy and conspiracy thrillers and their relationship to the world of real intelligence. He has recently published the monograph Paranoid Visions: Spies, Conspiracies and the Secret State in British Television Drama with Manchester University Press, as well as articles in the Journal of British Cinema & Television, the Journal of Intelligence History and Adaptation. He currently lectures in Television Studies at the University of Westminster and can be found on Twitter at @paranoidstylist.