N.B. This article contains SPOILERS relating to the FIRST FOUR EPISODES OF THE NEW SERIES OF TWIN PEAKS. Do not read this if you haven’t seen these and want to remain unspoilt.

A few years ago, whilst I was a PhD student, I remember persuading one of my non-UK housemates to join me on a Saturday evening to watch the broadcast of a new episode of Doctor Who (BBC 2005- ). It was definitely a Tennant-era one – my instincts tell me ‘Forest of the Dead’ (2008) – but that’s not as important as what they said fifty minutes later. As the credits rolled I tentatively asked ‘So, what did you think?’ Their response was ambivalent but the comment that has stuck with me concerned how I watched the episode: affectionately-toned, but words to the effect of ‘Dude, I don’t think you blinked for the duration of the entire episode! You were sat so far on the edge of the sofa that at one point I thought you were going to fall off!’ Aca-fan behaviour 101: deep absorption in a new instalment of a favourite series, blocking out immediate distractions and transfixed on the onscreen events (Brooker 2007).

I begin by recounting this anecdote because in the small hours of this Monday morning, as my partner and I huddled around our laptop with mugs of tea in hand, I was acutely aware that this mode of viewing was ‘happening again’ whilst the first two episodes of the new Twin Peaks aired. There I sat engrossed and desperately trying to take in every aspect of dialogue, mise-en-scene, aesthetics etc. and connect these with either fannish intra-textual knowledge, academic discourses within Television Studies, or (more frequently) both. I kept chewing over one question in my mind: how ‘new’ is new Twin Peaks? Can we still think of it as ‘the series that changed television’? Having blogged last week in anticipation of the first episodes arriving, this post offers reflections on these questions with regard to discourses of ‘quality’ television.

As expected, Twin Peaks began with minimal orientation for both new and non-fan audiences. Yes, Laura Palmer’s (Sheryl Lee) comments to Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) concerning seeing him again in ’25 years’ provided the initial context but that was it. Instead we were thrust into an unidentified monochrome-tinted location (the White Lodge?) where an aged Cooper (connoting the passing of time if not necessarily the ‘25 years later’ frame) enigmatically conversed with The Giant (Carel Struycken) about the significance of the number 430 and ‘Richard and Linda’. Needless to say, we haven’t encountered either of these individuals, or the required number (we have seen 15, 3 and 315 though), in the near-240 minutes of screen-time since.

Instead, the first major narrative incident of new Twin Peaks introduced us for the first time to Sam (Ben Rosenfield). Sam worked for an unnamed and unseen billionaire in a skyscraper high above the (beautifully-shot) city of New York and had been assigned two seemingly mind-numbing tasks. These were: a) observing a strange glass box featuring a circular hole which looks out over the city’s metropolitan vistas and b) replacing and storing memory cards for a multitude of digital cameras which were filming the box. However, in a (re-)demonstration of Lynch’s abilities as a director to invest everyday inanimate objects with sinister connotations, the long, unflinching shots of cameras staring out of the screen towards us as an audience created an unnerving atmosphere that recalled lingering shots of ceiling fans and record players in the original ‘Pilot’ (1990) episode.

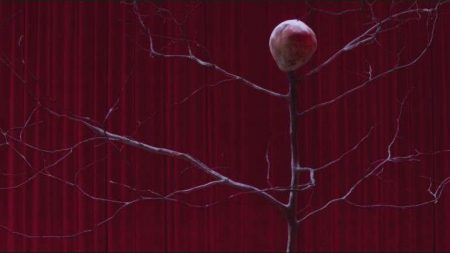

The only respite from Sam’s heavily guarded, and monotonous, tasks came via frequent visits from Tracey (Madeline Zima) who supplied Sam with coffee and unrequited romantic advances. However, during Tracey’s second visit, when the security worker guarding the entrance to the room housing the box had mysteriously vanished, Sam allowed Tracey in and they begin to initiate a sexual relationship. Here new Twin Peaks’s distinguishing of itself its former incarnation began: firstly, in line with ‘quality’ TV drama’s culturally-masculine tendencies, we get graphic, primarily female, nudity as Tracey removed her clothing. The couple’s amorous relations were violently interrupted in a bloody and brutal manner, however, as they had their heads burrowed into by a ghost-like figure who appeared in the glass box (and looked reminiscent of the creature which intruded into Agent Hawk’s (Michael Horse) pre-publicity video last December). Here it was: new Twin Peaks’s first unnerving sequence and it was undeniably affective in achieving its goals.

However, if our encounter with Sam and Tracey drew a symbolic line between Twin Peaks ‘then’ and ‘now’ (given its home on ABC and FCC guidelines in the early 1990s, there was never any nudity at One Eyed Jack’s), this incident (and subsequent others such as meeting Jade (Nafessa Williams) in episode 3) felt like more of the same in US ‘quality’ TV drama. As Janet McCabe and Kim Akass argued in 2007, HBO has generated the distinctiveness of its original programming by using the “discourse of the illicit” constructed around network US TV and using its status as outside of regulatory control to offer frank representations of nudity, sex and violence. Whilst this imagery was ‘new’ for Twin Peaks, it also felt like the series negotiating its institutional context by intertextually locating itself within long-established trends via shows like The Sopranos (HBO 1999-2007) and Sex and the City (HBO 1998-2004). The message communicated was ‘It’s not old Twin Peaks, its Showtime’s Twin Peaks’.

What’s more, the graphic body horror of Sam and Tracey’s demise also symbolically demarcated between network-orientated 90s ‘quality’ TV and contemporary, premium-subscription equivalents: where the original brought us the brutalisation of the human body in a deeply unsettling and unrelenting manner when we learnt who killed Laura (Sheryl Lee), there was always a restrained use of blood in the original. New Twin Peaks quickly defies this trend by sending the red stuff flying freely but, through doing this, again intertextually locates itself amongst its ‘quality’ contemporaries like Game of Thrones (HBO 2011- ), Daredevil (Netflix 2015- ) and Hannibal (NBC 2013-15) rather than furthering TV drama’s representational and generic parametres.

Moreover, the way in which the first unnerving attack of new Twin Peaks despatched its victims further aligned itself with trends within contemporary ‘quality’ television. Doing this involves reading Sam’s character as a substitute for ourselves-as-viewers and that the transparent, technologically-advanced glass box that he stares intently is a substitute for the television/viewing screen. Sam, and his ongoing obligation to digitally-document everything, can therefore be read as an example of what Jason Mittell (2015: 52) has named “forensic fandom” where “contemporary programs …[demand] detailed dissection …[of] plotting and enigmatic events in addition to storyworld and characters.” Understood from this perspective, Sam and Tracey’s decision to neglect the task set and turn away from ‘watching the screen’ breeds negative consequences (here graphic death) as, by breaking your attention, you miss something which has disastrous implications for your status as a viewer.

Whilst the trope of monitoring and surveillance has arisen in Lynch’s previous cinematic outings such as Inland Empire (2008) and Lost Highway (1996), the emerging threat through the pseudo-screen also opens itself up to being read through discourses of the horror genre such as the fear of ‘monsters in the static’ which Jeffery Sconce (2000) has noted dates back to interference on wireless radios is recalled and reconfigured here. Alternatively, as Matt Hills (2012) writes, diegetically-inscribing a hyper-attentive viewer is a recurrent trope of ‘quality’ dramas as Carrie Mathison (Claire Danes) of Homeland (Showtime 2011- ) demonstrates. This is something that the original Twin Peaks arguably helped initiate by foregrounding Agent Cooper’s attention to onscreen details and having the character reveal the reflection of James Hurley’s (James Marshall) motorcycle in Laura Palmer’s eye whilst watching the video of hers and Donna Hayward’s (Lara Flynn Boyle) picnic. ‘New’ Twin Peaks therefore reworks this idea, albeit in an alternative institutional context where greater violence towards the (naked) human body is permitted, but the message remains the same: don’t let your attention wander.

Reading these comments may suggest discontent with what I’ve seen from the new Twin Peaks. The truth couldn’t be farther from this, however. Despite the first episode’s intertextual alignments with both established trends in ‘quality’ TV drama and Lynch’s oeuvre, the experience of watching the return has, for me as both a fan and TV scholar, been intense and quite emotional. As someone who was ‘late to the party’ with Twin Peaks, encountering it first on DVD in the mid-2000s, the experience of watching the show unfold as it is aired is exhilarating. Moreover, despite the show’s alignment with the trends mentioned here, the re-filtering of Twin Peaks’s iconography into a different institutional and technological context fascinates. Pacey shots across an endless black and white chevroned floor and the use of CGI to meet hitherto unseen characters such as the (frankly terrifying) Evolution of the Arm exemplify this point well.

What’s more, despite the critiques raised, there are other ways that Twin Peaks is differentiating itself from contemporary ‘quality’ TV tropes. These include the slow, at some points almost glacial, pacing of the narrative, the use of sound including long stretches devoid of dialogue and the lack of non-diegetic music or recognisable leitmotifs from the previous series (we have to wait until episode 4 to finally hear Laura Palmer’s Theme (Badalamenti 1990)), and the disorientating, staccato use of editing during episode 3 when Cooper arrives at his location following expulsion from the Lodges. Finally, a special mention should be made regarding the new Twin Peaks and performance – especially with regard to MacLachlan and how he has portrayed the ‘Good Cooper’ moving from ‘Empty Shell Dale’ through to ‘Mr. Jackpots’ and then ‘Dougie Jones’. All of this points different towards multiple scholarly areas where the new Twin Peaks can be discussed and analysed by others (and I look forward to reading these).

In conclusion, then, I hope that this post has summarised a few key areas for thinking about the emotional and interpretive experience of watching a returned favourite text: the feelings and type of viewing experience this can inspire as you shuttle from fannish-to-academic readings; a critical glance towards the cultural value that we align with the notion of ‘innovation’ against ‘repetitiveness’ when discussing ‘quality’ TV drama; allusions towards the ongoing need for reflexivity to be demonstrated towards the taste preferences of different interpretive communities for ‘quality’ TV drama, perhaps. One thing remains, however: learn from Sam and Tracey and keep watching the box.

References:

Brooker, W. (2007) ‘A Sort of Homecoming: Fan Viewing and Symbolic Pilgrimage’, in C L Harrington, J Gray and C Sandvoss (eds.) Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World. New York: New York University Press.

Hills, M. (2012) ‘TV Review: Homeland’. Times Higher Education, 16/02/12, https://timeshighereducation.com/features/culture/tv-review-homeland/419049.article. [Accessed 24/05/17].

McCabe, J. and Akass, K. (2007) ‘Sex, Swearing and Respectability: Courting Controversy, HBO’s Original Programming and Producing Quality TV’, in J McCabe and K Akass (eds.) Quality TV: Contemporary American Television and Beyond. London: I.B. Tauris. pp.

Mittell, J. (2015) Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary TV Storytelling. New York: New York University Press.

Sconce, J. (2000) Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television. Durham: Duke University Press.

Ross Garner is a lecturer in TV Studies in the School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies at Cardiff University. His research interests cover cult TV, paratextuality, branding and debates concerning mediated space and TV-derived tourism. He has recently published articles exploring these issues in Popular Communication, Series: The International Journal of Serial Narratives and Tourist Studies and is currently working on the monograph Nostalgia, Digital Television and Transmediality (Bloomsbury)