I am writing this towards the end of Week 7, which means that by the time it’s online most of us will be around two-thirds of the way through our first term/semester/trimester/block, and entering the home stretch before that much-needed Yule break. I don’t know about you, but I am really rather relishing the return to face-to-face teaching. I can’t honestly say that every session has been pure gold, but there’s something about standing up in a lecture theatre and actually seeing if/how the students are responding that I have genuinely missed over the last few years. At UAL, I have (re-)instituted a fairly traditional lecture/screening/seminar set-up, and it’s nice to see students enthusiastically discussing the viewing material – both first years and second, for whom this is an equally fresh experience (the latter were kept entirely online for ‘theory’ content last year) – in seminars. Last year I gave students links to screenings online before class, but actually getting them into a lecture theatre and switching the lights out is far more effective. They even applaud at the end! It’s been mainly film so far, but tomorrow the first years get their inaugural taste of television series, serial and flexi-narratives.

Fingers crossed…

It’s tiring, of course – but then, so was online teaching. For the latter, I usually needed a lie down afterwards because I had spent two to three hours absolutely focused on keeping my vocal energy up, making sure all the clips played (with sound!), hopping in and out of lethargic breakout rooms, and sorting the wheat from the chaff of incoming chat messages. It was mentally draining. Now we’re back to face-to-face, it’s just good, old-fashioned physical tiredness: the result of leaping around the stage or circulating in the seminar room as I monitor student activities.

All of which means that, while I am happy to indulge in a bit of serial drama over supper with my partner (is it just me, or did The Devil’s Hour make little sense unless you actually went online afterwards to read the explanation on Den of Geek?), at the very end of the day – when the dishes are done, and I have walked my beloved home – I need to unwind with a bit of unchallenging TV drama. Ideally, I seek something 50 minutes long, in an episodic series format – so I don’t need to remember what happened in the previous instalment. For the last few months my comfort telly of choice has been Space: 1999: the Gerry Anderson science fiction show that had actual live actors (though some were more lively than others), combined with some rather splendid model work, as opposed to daft puppets. Can I make a heinous confession? I have never really liked Thunderbirds or Captain Scarlet. Even in my youth, I just thought they looked silly – and their heads were too big.

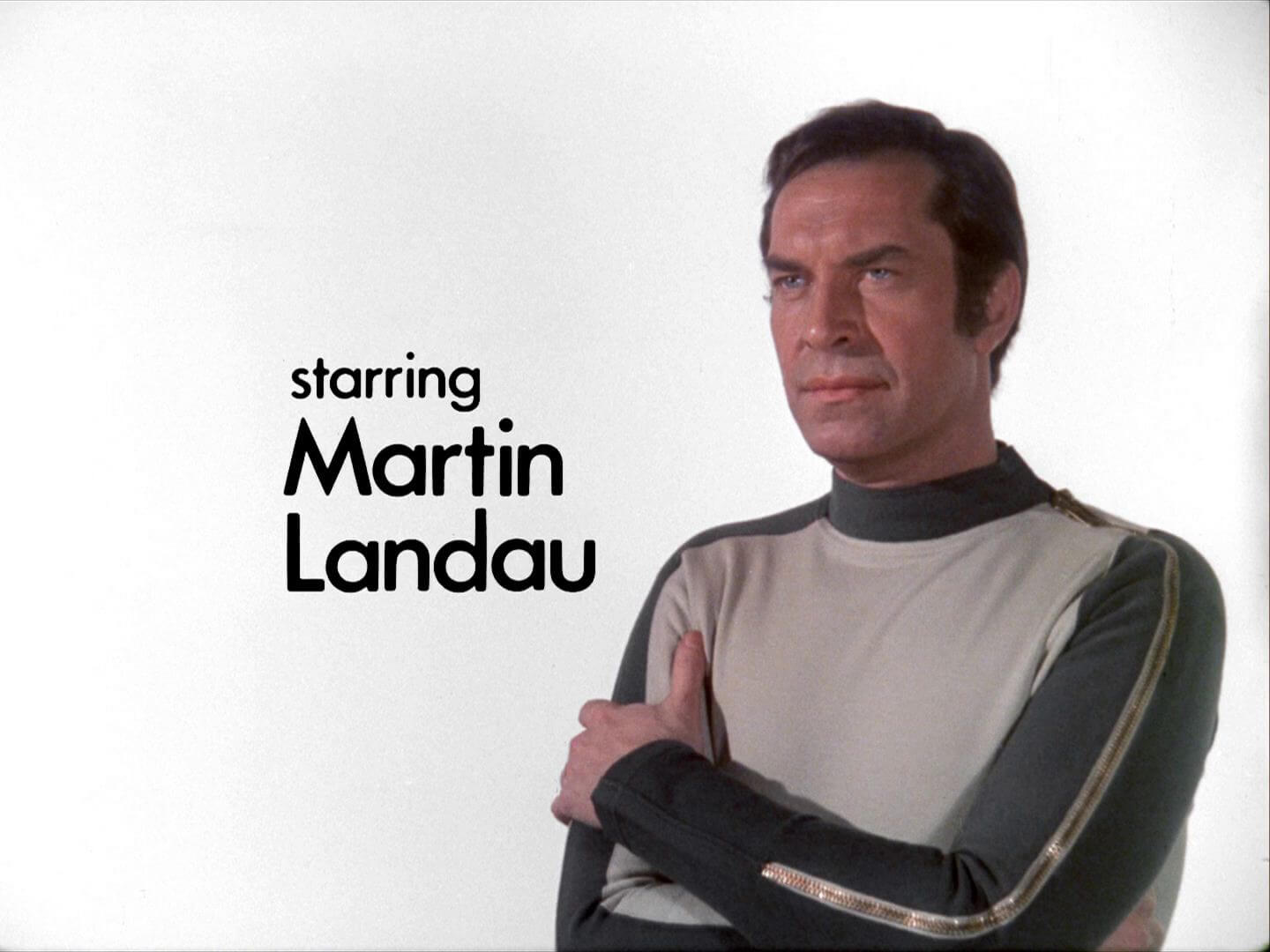

For those unfamiliar with Space: 1999, there is a clue in the title. It was set on Moonbase Alpha (I’m not sure if there was a Moonbase Beta) in the year 1999 (which now seems a little ambitious, but, you know – this was 1975). In episode one new commander John Koenig (played by Martin Landau – oh, so splendid in North by Northwest and Ed Wood, but oh, so lacking any kind of charisma here) takes charge just before an explosion blows the moon wildly out of orbit. After passing through time warps, black holes, time eddies, time fissures and – for all I know – Eddie Fishers, there seems little hope of a return to Earth for the Alphans, who settle down to the business of finding a new habitable world, meeting plenty of weird and wonderful life forms (generally hostile) along the way.

The show was originally envisioned as the second season of another series co-created by Anderson and wife Sylvia, UFO, but set on the moon – only by the time the plug was pulled on that concept, work had already commenced on the expensive moonbase models. These, along with the stylish miniature spacecraft known as ‘Eagles’, were really the show’s USP. The whole thing was made on film, single camera, which meant that the shift from model work to live action was seamless – at least when compared to what has been called the ‘piebald mix’ of film and videotape on contemporaneous shows like Doctor Who.

Now, if I had to choose my desert island viewing selection, Doctor Who would win against Space: 1999 every time – but it has been interesting getting the chance to compare the two. Although there is a slight crossover in terms of the creative teams (regular ’99 writer Johnny Byrne would later contribute to Who, as would Pip and Jane Baker, while former Who script editor Terrance Dicks wrote one episode of Space: 1999), the programmes are quite distinct. However, as a five- to six-year-old I watched both. Who was famously enjoying a period of renewal at the time under new series producer Philip Hinchcliffe and script editor Robert Holmes. This was the golden era of Wirrn, Zygons, Krynoids and Kraals – not to mention Dalek creator Davros, and the similarly egomaniacal Sutekh the Destroyer, who left dust wherever he trod (it could get a bit messy). Many of these were immortalised on a range of Weetabix cards, which I eagerly collected (and still have).

Space: 1999 was broadcast in my ITV region on Saturday mornings, and therefore presented less of a distraction with regard to my teatime viewing than Buck Rogers in the 25th Century would just a few years later. However, Dinky did release toy versions of the Eagles in various colours (though they were always off-white in the show), and I was given the blue version for Christmas (yes, I still have it).

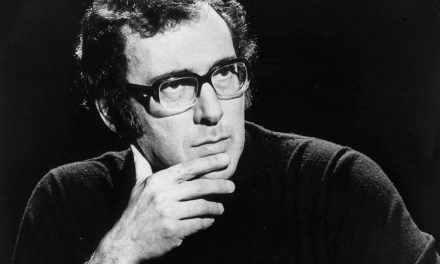

Space: 1999 is particularly notable for undergoing a major re-vamp after series one, in which half the regular cast were culled, a new theme tune was composed, and the Moonbase control set was redesigned/replaced. Received wisdom has it that the first series – which was serious, cerebral, and featured heavyweight actor Barry Morse as the show’s resident science boffin, Victor Bergman – was superior to the second, in which Fred Freiberger – infamous for helming the third season of Star Trek to its doom – replaced Sylvia Anderson as producer, and Bergman was ousted in favour of a shape-shifting alien called Maya, played by Catherine Schell.

I am now going to make another shocking confession:

I actually prefer the second season.

There – that’s put the cat among the pigeons, hasn’t it?

Basically, series one is quite dull. The costumes – which for some reason gain designer Rudy Gernreich an on-screen credit at the start of each episode – look like beige pyjamas with a zip up the arm. While there are initial attempts to imply a degree of friction amid the supporting characters – Prentis Hancock as second-in-command Paul Morrow, and Clifton Jones as computer operations officer David Kano – these fizzle out fairly early on. Despite the presence of Barbara Bain (real-life partner of Landau at the time) as medical chief Helena Russell, Zienia Merton as data analyst Sandra Denes, and Suzanne Roquette as ‘one line an episode’ operations officer Tanya Alexander, female characters generally have little to do, and seldom get to leave the base – a task usually left to third-in-command chief pilot Alan Carter (Nick Tate); the only character who seems to possess any degree of charm or personality.

Sexual tension – if that’s your idea of a good time – is lacking. There is a moment in either ‘Black Sun’ or ‘Collision Course’ (there are several stories in which the crew of the base sit around and do surprisingly little in the face of what seems like impending disaster, so I forget which this was) where Paul strums his guitar fatalistically to Tanya, and Koenig and Russell occasionally look as though they might quite like to hold hands – but that’s about it.

Aside of Eagles taking off, flying, landing and sometimes crashing, there is not a great deal of action. The Alphans have what looked to a five-year-old like really quite cool space weapons – a little like those devices you hold against a wall to check whether electrical current is running through concealed wires – but hardly ever use them, despite pretty much every extra-terrestrial life form they encounter being out to get them in some way.

The Alphans meet plenty of aliens, but hardly any monsters. Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee, Leo McKern and Peter Bowles stride around in strange wigs and make-up, but actual nasties are quite thin on the ground – except for in ‘Dragon’s Domain’, where something horrible with tentacles puts paid to Michael Sheard and Susan Jameson in a flashback scene; yes, the guest casts are usually very good. Philip Madoc appears (briefly) as the outgoing commander in the opening episode, ‘Breakaway’, Paul Jones provides an (again, brief) love interest for Sandra in ‘Black Sun’, and ‘Force of Life’ sees a pre-Lovejoy Ian McShane being taken over by an alien force.

Having completed my epic viewing marathon just last week, it occurs to me that I have little or no memory of watching series one as a child – though I almost certainly tuned in regularly. However, Doctor Who of the time is still quite vivid to me. I can remember thrilling at the not-yet giant Robot’s attack on Tom Baker’s Doctor at the end of his second episode (‘This new man hasn’t lasted very long,’ I thought). I recall Styre removing his helmet at the end of ‘The Sontaran Experiment’ Part One. I was definitely at my nan’s when Davros instructed Garman to insert the first Dalek weapon into its slot in ‘Genesis of the Daleks’. I was also there when Sister Lamont turned into a Zygon. Yes, my recollection of 1975 Who is quite strong, but – as Noah the Wirrn might have said – I have no memory of John Koenig and his beige base crew from that time.

Series two is a different story. In the opening episode, ‘The Metamorph’, no explanation is provided for the fact that Paul, David, Tanya and Victor have disappeared (a line was apparently scripted to cover the latter’s death from a leaky spacesuit, but like Bergman it did not survive to the broadcast version). Sandra is now called Sahn, which is also not explained, and the character appears only infrequently. Alpha’s second-in-command is now (and, from the diegesis, apparently always has been) beer-brewing Tony Verdeschi (Tony Anholt), who begins romancing Maya almost as soon as she joins the crew. Maya, we soon find out, is from an alien race called the Psychons, and chooses to abandon her dying home world after her father, Mentor (Brian Blessed, in his second role on the series) begins hatching plans for universal domination.

Maya and Tony’s flirtatious banter often forms the basis of the (intended) humour of many of the episode codas that now became part of ’99’s signature in the Freiberger era. No matter what manner of terrifying menace the crew has just very nearly not overcome, there are always laughs a-plenty in the closing moments – just like on Star Trek, when Bones used to give vent to his rampant speciesism by calling Spock a ‘damned, green-blooded Vulcan’, Kirk would chuckle and the Vulcan would raise a quizzical eyebrow.

Every episode.

Space: 1999’s version of this is to have Tony sexually harassing Maya in the workplace, telling her she knows she wants him really, only for Maya to transform into a short, middle-aged woman (i.e. not coded as being as conventionally attractive as Catherine Schell), and dare a reluctant Tony to kiss her.

It’s hilarious stuff, and if that is not enough, Koenig and Russell are also now embracing, gazing into each other’s eyes, and even occasionally locking lips. In one magical scene, Maya transforms into a Barbara Bain lookalike, and poor Koenig has to kiss both women in order to work out which is whom.

Yes, the sexual politics were a little dubious. At the end of ‘The Seance Spectre’, in which a paranoid member of the crew leads an attempted mutiny in the mistaken belief that the latest world the Moonbase encounters is a habitable paradise, the crew are forced to watch boring screenshots of trees, meadows and streams, in order to cure them of their longing for a new Earth. All except Alan and Tony, that is – who view images of bikini-clad females instead.

Those guys!

I feel I may not entirely be selling series two to you, but it does at least make more of a stab at providing its characters with a modicum of personality than the first outing – even if much of this just revolves around people fancying each other, and not liking Tony’s home brew. The costumes have improved, at least. The crew now have name badges, and sport different-coloured jackets over their jim-jams. They also zap alien menaces – many of which are actual monsters – on a more regular basis (though looked at today these rubber suit creations pale in comparison with what was going on in Doctor Who at the time, particularly the superb masks of John Friedlander). The opening titles (now accompanied by Derek Wadsworth’s driving score, replacing Barry Gray’s original brass fanfare and electric guitar disco freakout) even feature Koenig mid-zap, whereas in series one he just stood there, like a lemon.

Many of these developments, which repositioned the show as an action-adventure space fantasy, rather than ‘hard’, existential sci-fi, passed me by at the time, because by the end of ‘The Metamorph’ I had fallen head over heels in love with Maya. I’m not sure if it was her eyebrows (which looked like they were made out of Sugar Puffs, and therefore delicious), the fact that she could transform into almost any creature at will, or (less likely) Catherine Schell’s consistently strong performance – but I was smitten, and secretly relieved that she never quite succumbed to Tony’s flirtations.

I was in luck, too, because – just as Mr Spock increasingly became the focus of Star Trek after producers like Freiberger realised how popular the character was – a number of series two episodes revolved around the Psychon newcomer. In ‘Space Warp’ Maya loses control of her ability to transform, turning into a variety of violent and unstoppable creatures before a cure is found. In ‘Dorzak’, she makes a terrible error of judgment when she protests that the last other surviving Psychon is a good guy (he isn’t), while in ‘The Rules of Luton’ (nothing to do with the football team, or the airport), she and the wounded Koenig are forced to battle monstrous creatures for survival on a sentient alien planet. Lastly, final episode ‘The Dorcons’ is driven by Patrick Troughton’s desire to get his hands on Maya’s brain stem – but only because it will give him eternal life (yes, the guest cast was still impressive).

These are the episodes I remember best of a Saturday morning – though it’s odd the tricks memory can play. For example, I recall ‘The Lambda Factor’, in which the climax sees a resentful female crew member with strange mental powers forcing Maya to turn into a slug, being all about the torture of my poor darling, when in fact this scene is only a brief one.

Such was my six-year-old passion…

It was not long, however, before Maya had a rival. Over on BBC1, Sarah Jane Smith had been dumped unceremoniously back on Earth, and the Doctor had a new companion: noble savage Leela of the Sevateem, played by the excellent Louise Jameson. She couldn’t transform into small animals, but she wore chamois leather and knew how to wield a knife. I don’t honestly recall thinking about these latter factors much at the time, but I was torn. Was it Maya or Leela I most wanted to play kiss chase with (an obvious prelude to marriage)?

All I can say is that when Christmas 1976 rolled around, it was a Denys Fisher Leela doll that took pride of place in my stocking. I’m not sure they even made a Maya doll, which probably speaks volumes. Following the cancellation of Space: 1999 the following year, my shape-shifting sweetheart was ultimately forgotten – though that might well have changed had the mooted Maya spin-off series been commissioned.

I have enjoyed revisiting series two of Space: 1999, even if its sexual politics sometimes make it a qualified pleasure. However, with all due respect to hard core fans (Spacers? 99-ers?) I think it will be a while before I attempt to discover the subtle pleasures of the more celebrated series one.

What next? Well, maybe a little Star Trek: The Next Generation – a far more successful science fiction ensemble – or perhaps a nice episodic crime drama (I’ve still got three series of The Sweeney to get through). For the moment, though, there is still a month of lecture material to prepare.

Good luck everyone; I’ll see you the other side of Christmas…

Dr Richard Hewett is Senior Lecturer in Contextual Studies for Film and Television at University of the Arts London. He has previously contributed articles to The Journal of British Cinema and Television, The Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Critical Studies in Television, Adaptation, SERIES – International Journal of Serial Narratives and Comedy Studies. His 2017 monograph, The Changing Spaces of Television Acting, was published in paperback form in 2020. For further information on academic publications, see here.

Glad you’ve had chance for a re-watch Richard! Must find the time for one myself. I think my own tastes lie somewhere in the middle between Year One and Year Two – a perfect blend on the borderline between the two where a high concept and character drama can also be pepped up with the odd monster or action sequence.

And so interesting to see your different viewing of the show on first run in a slot *very* different to mine… especially compared to the good Doctor. We had about ten episodes on Thursday evenings at 8pm – which was fine – after which the next seven or so were shifted to around 6pm on Saturdays, *opposite* “Doctor Who” (meaning that I didn’t catch them for many years). The remaining seven shows then didn’t air until Spring 1976 and Summer 1977… As for Year Two, I was able to view this in glorious monochrome from an adjoining region that scheduled it at – goodo! – around 6pm on Saturdays from September 1977 (meaning that I only got to see the concluding halves of stuff like “The Metamorph” years later…) before switching to the more accessible slot of Thursday afternoons for a few months (with the last few secreted around the schedules over the next two years…). Oh, Saturday mornings would have been *so* much easier…

Glad you’re back to sharing your televisual passions with your students in situ! My wife and I still delighted in having young visitors whom we can share television rarities with and share their delight of discovery! 🙂

All the best

Andrew

Many thanks, Andrew! You have made me doubt whether I did, in fact, watch series one when it was first on… We only had one TV, and I doubt my dad would have been up for Thursday evening sci-fi. I definitely saw series two on Saturday mornings; we got both LWT and Anglia in my part of Essex, but I can’t remember which would have shown it… I do remember looking at the magazine Look-in and being amazed at the variation in schedules between the different regions.

I hope all’s well!

If you venture into the catacombs here…

cstonline.net//cstonline.net//catacombs.space1999.net/main/pguide/viblwt.html

… you may be able to navigate to the Moonbase Alpha in your ITV region… 🙂

All the best

Andrew

What a great resource! Thanks again, Andrew.

All the best

R

Really enjoyable though I am immune to the delights of outer space. Glad you are enjoying your teaching again.