Fig. 1: This is our BBC. Source: https://bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0bln3nw

This week is the 100th anniversary of the BBC, and the schedules offer various programmes that celebrate it, picking moments, objects and people from across the institution’s history. Rather than giving another selection of important bits of the BBC’s story, I decided this blog should be about some of my own relationships with BBC programmes and people. This follows BBC’s own lead, since it has responded to anxieties about audiences’ lack of engagement with its programmes and indeed the whole concept of linear Public Service Broadcasting by adopting various discourses of personalisation. The iPlayer has a “My programmes” tab, there is a “My sounds” area in the audio app, and the 100th anniversary was promoted across BBC services by an “Our BBC” trail (Fig. 1). Right now, the ads for World Cup football coverage strive to remind us how national sporting events, like royal ceremonies and national crises, are when BBC gathers us together as an (imagined, and sometimes real) community. The BBC is all about us, or me, and how one becomes the other.

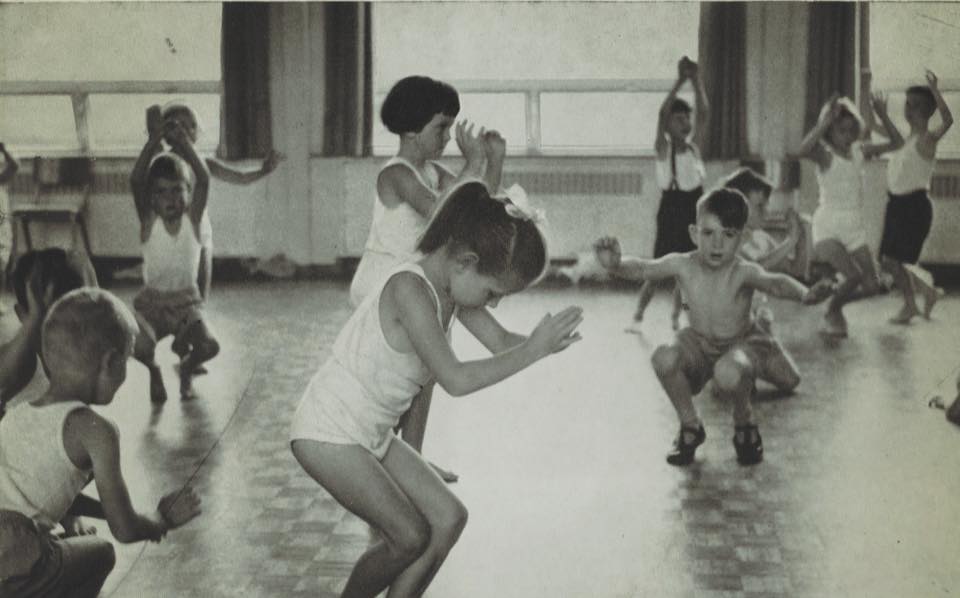

My BBC starts not at home but at school, and it starts with radio, not television. BBC created programmes for schools, on radio from 1924 to 2018 and on television from 1957-95, across the full range of subjects and for younger and older children. Programmes were broadcast at set times so schools could integrate them into timetabled lessons. At school and at home, children were expected to listen and view with an adult or with other children. For younger audiences, interactivity meant joining in with games and singing along with programmes. When I started at Canonbury School in London in 1968 after my family moved house there, my class, clad in just our vests and underpants, gathered each week in the large, open assembly hall for BBC Schools’ Music and Movement on radio (1934–73) (Fig. 2). On 31 January 1968, I clearly recall, the theme of the programme was “Spring” so we each found a space to curl up on the floor as small as we could, imitating a seed or bulb in the soil. Then, accompanied by piano music from the radio, we gradually uncurled, raising ourselves upright, extending arms and hands upward to express the blossoming of a plant or tree. I was delighted that my teacher praised my execution of this sequence. We skipped and hopped around the room at the BBC voice’s command, and for me then, BBC meant listening and doing: following a story and taking part in it.

For older children, interactivity with BBC programmes could include encouragement to take part beyond that programme in sport or fundraising for charities, or participation in programmes’ fan networks. Blue Peter (1958-present) invited viewers to interact by writing letters, and in 1970 (I think) I wrote to the programme in response to an item about the changing fashions of the day, enclosing my drawings of co-host Valerie Singleton in dresses of different lengths – mini, midi and maxi, which she had modelled on screen that week. Val had invited me to express my view: BP presenters always adopted direct address to the camera, positioning me as both an individual ‘you’ and as part of the ‘we’ of the audience community. By writing in I could be a participant in the programme as well as a passive viewer, and I still have a sense of loyalty to Blue Peter that meant, decades later, leaping at the chance to supervise Amanda Beauchamp’s PhD thesis on the programme.

The world of the mid-1970s felt out of joint to me, and BBC gave form to my expectations of imminent disaster in the dystopian dramas The Changes (1975) and Survivors (1975-77). I had become a regular viewer of Doctor Who (1963–89, 2005–present), starting with the last few serials featuring Patrick Troughton, through the Jon Pertwee era and into Tom Baker’s time as the Doctor. I was fascinated by the elegant, well-mannered but deadly ‘Robots of Death’ (1977) who rebelled against the decadent, human aristocracy whom they served, and by the Victorian Gothic of ‘The Talons of Weng Chiang’ (1977) in which giant mutant rats stalked the same London Underground tunnels through which I travelled to school each day (Fig. 3). As a teenager BBC TV offered metaphors and stories that gave focus to my anxieties as well as my pleasures.

In 1985 I was a Masters student at Sussex University, watching much less television, but I wrote about docudrama in BBC’s Play for Today (1970-84), which had just ended, in my dissertation and my path towards being a TV academic was taking shape. After a PhD on film and TV narrative, in 1989 my first job, at the University of Reading, was a “new blood post” for younger lecturers and an aspect of its newness was creating courses in Film and TV studies within an English department. I had a VHS recorder in my office and another one sat on a wheeled trolley for use in teaching, and many of my evenings and weekends were spent hooking them up with SCART cables to run off multiple copies of programmes for students to study. Much of my syllabus was BBC material, and a lot of it reflected my own BBC TV memories and preferences and the rather conventional canon they produced. There was Cathy Come Home (1966), The Cheviot, The Stag and the Black, Black Oil (1974), and The Singing Detective (1986), for example. Teaching TV largely meant teaching BBC drama, its history and its recent landmarks, and trying to persuade students of its value.

I have never had much direct interaction with BBC programme makers; just a few interviews on BBC Radio Berkshire, a BBC South regional TV documentary and talking to BBC researchers who wanted my expertise for free. But for over 20 years I have worked on BBC Written Archive materials, and one of my strongest memories is of BBC archivist Jacqueline Kavanagh instructing me how she wanted the strings holding musty memos together re-tied in a neat bow after I had consulted them. There was such pleasure in reading and handling the paperwork behind the programmes, and this could also extend to meeting their makers. The most notable such occasion was at the “On the Boundary” conference on TV drama in 1998, organised by Madeleine Macmurraugh-Kavanagh for the big, well-funded research project that I ran with Stephen Lacey. I chatted to many of the actors, writers and directors who came, and to BBC movers and shakers like the producers Tony Garnett, Michael Wearing and Kenith Trodd, some of whose talks appeared in our subsequent book (Fig. 4). This was another kind of interaction with the BBC, in which aesthetic, financial and policy decisions became personified and individualised, as well as institutional. My BBC was a culture made and sustained by real people.

For all its faults, across nearly all my life the BBC has engaged me. It has drawn me actively into listening and viewing, implicitly asking me to take a place amongst the audience conjured up by its programmes. In doing so, BBC broadcasting created relationships for me. My experiences of the BBC are an aspect of belonging to, and having a place in, my home, family and a whole range of sectors and groupings in society. Now, I often find myself writing about its achievements, cautioning against undermining it and recounting quirky little stories about half-forgotten moments in its history. For good and ill, my BBC has enabled, shaped and defined me, and I bet it has done something similar for you, and us: each of us.

Fig. 4: Cover of British Television Drama: Past, Present and Future, edited by Jonathan Bignell, Stephen Lacey, and Madeleine Macmurraugh-Kavanagh.

Jonathan Bignell is Professor of Television and Film at the University of Reading. He grew up in London, did a degree in English at Jesus College, Cambridge, followed in 1984 by an MA and then a PhD in film and TV at the University of Sussex. He taught literature and media at Reading from 1989-99, then moved to Media Arts at Royal Holloway University of London. Since 2002 he has worked in Reading’s department of Film, Theatre & Television, focusing increasingly on research into British television history. His published work is listed on his Reading web page, and many of his papers and projects are available free on Academia.edu

References

Beauchamp, A., “A double-decker bus, an elephant and 300 Girl Guides: Analyzing ‘space’ and ‘place’ in Blue Peter”, Journal of Media Practice, 12 (2012), pp. 235-243. 10.1386/jmpr.12.3.235_1.

Bignell, J., S. Lacey and M. Macmurraugh-Kavanagh (eds), British Television Drama: Past Present and Future (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000).

What a super personal history. Yes… when I read things like this, I really am reminded that it’s “Our BBC”!

Thanks Jonathan! Hope all is good with you! 🙂

All the best

Andrew