I recently attended an online course at Aarhus University titled, “Transnational VoD Cultures”. Aimed mainly at PhD researchers, whose research is in some way affected by the transnational nature of streaming platforms and television today, the course made me think about the transnational nature of television in South Africa, where I live. My research is focussed on three crime shows on Showmax, a South African SVoD streaming platform, and my thoughts around the transnational nature of streaming have been about Showmax’s positioning in Africa, and its distribution of South African and African content within Africa.

In contrast, at the Aarhus course, Netflix as a transnational platform dominated presentations and group discussions. The economies of transnationalism, identities in transnational shows, the politics of transnationalism, and the impact on national viewing cultures all featured in discussions of Netflix and its current global domination. What struck me about the presentations was that the national broadcasters in Scandinavia appeared to truly embody the title of national broadcaster. The Danish national broadcaster, DR, and the Norwegian national broadcaster, NRK, before the incursion of Netflix, made, commissioned, and screened local content for their respective citizens. Granted, this is probably in line with the public service mandates of these national broadcasters, but I also got the impression that Danes and Norwegians watched mostly Danish or Norwegian content, maybe some shows from the BBC and from the United States, but small screens seemed to have been dominated by local stories and events. Comparing these situations to my own growing up in South African in the 1970s and 1980s, it occurred to me that South Africa had always been a transnational television audience.

South Africa was late to the global television party, only launching television broadcasting on the fifth of January 1976. The National Party (NP) apartheid government had been concerned that TV would corrupt its citizens with ideologies and practices that were contrary to their racist ideology of separate development. They used arguments about the cost of infrastructure and the nascent technologies to avoid introducing TV to South Africans. Intriguingly, their fear that TV would make citizens question apartheid, suggests they were already aware that television shows in South Africa would be from around the world, and would represent races living and working together. According to Carin Bevan (2009), the event that forced the NP to seriously reconsider their stance on TV was the moon landing in 1969. While the rest of the world could watch this (trans)planetary event, South Africans could only listen to its broadcast over radio. Some wealthy and tech-savvy citizens did have TV sets, but this would have been a handful. White South Africans were understandably upset that they were being left out of such monumental global events.

When television launched in January 1976, South Africans got to see South African children’s shows and news programmes in English and Afrikaans, and an Afrikaans drama. On that eventful night, they also got to watch the American The Bob Newhart Show! Before my parents acquired a TV set, they would bundle us into the car once a week, and we would travel the ten kilometres or so to my grandparents to watch another American show, Rich Man, Poor Man. Once we had our own Philips TV set, I watched English and Afrikaans children’s TV shows in the late-1970s and 1980s. Many of the English shows were foreign, but also some of the Afrikaans ones. Children’s and teen programmes I watched included Thunderbirds (which was dubbed into Afrikaans) (US), Simon in the Land of Chalk Drawings (UK), The Wombles (UK), Heidi (Japanese), Pipi Langkous (Swedish), Little House on the Prairie (US), The Lost Island (Australia), Little Darlings (US), and the list goes on. Adult programming included Blitspatrollie (The Sweeney) (UK), Derrick (Germany), Alpha 1999 (UK), Arsène Lupin (French), Columbo (US), Charlie’s Angels (US), and this list continues too.

From the beginning of television in South Africa, households that could afford TV sets watched stories from around the world. It is even likely that most of what I watched on terrestrial TV was foreign content. The difference between then and now, was that growing up, I was unable to select these shows from a bouquet of offerings – it was all simply there for me to watch. So, despite the NP’s early fears of radical ideologies and cultural influence, and despite their iron grip on broadcasting, they allowed a plethora of foreign shows to shape our hungry minds. The South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) did produce its own shows across genres and formats, but this production focus was on content for white South Africans, and foremost for white Afrikaans-speaking South Africans. This narrow focus also meant that, as in other media, news programmes avoided reporting the violent reality of life for Black South Africans. Only in the early- to mid-1980s did the SABC allocate channels for black South Africans who spoke local Nguni and Sotho languages. Programmes were produced specifically for this black viewership in the languages of the channels. Under apartheid, my family was classified as coloured, and there was no consideration around any special programming for this apartheid population category. Because we lived in a big city, when my parents could eventually afford a TV set, we got to watch whatever was being broadcast for white citizens in urban areas.

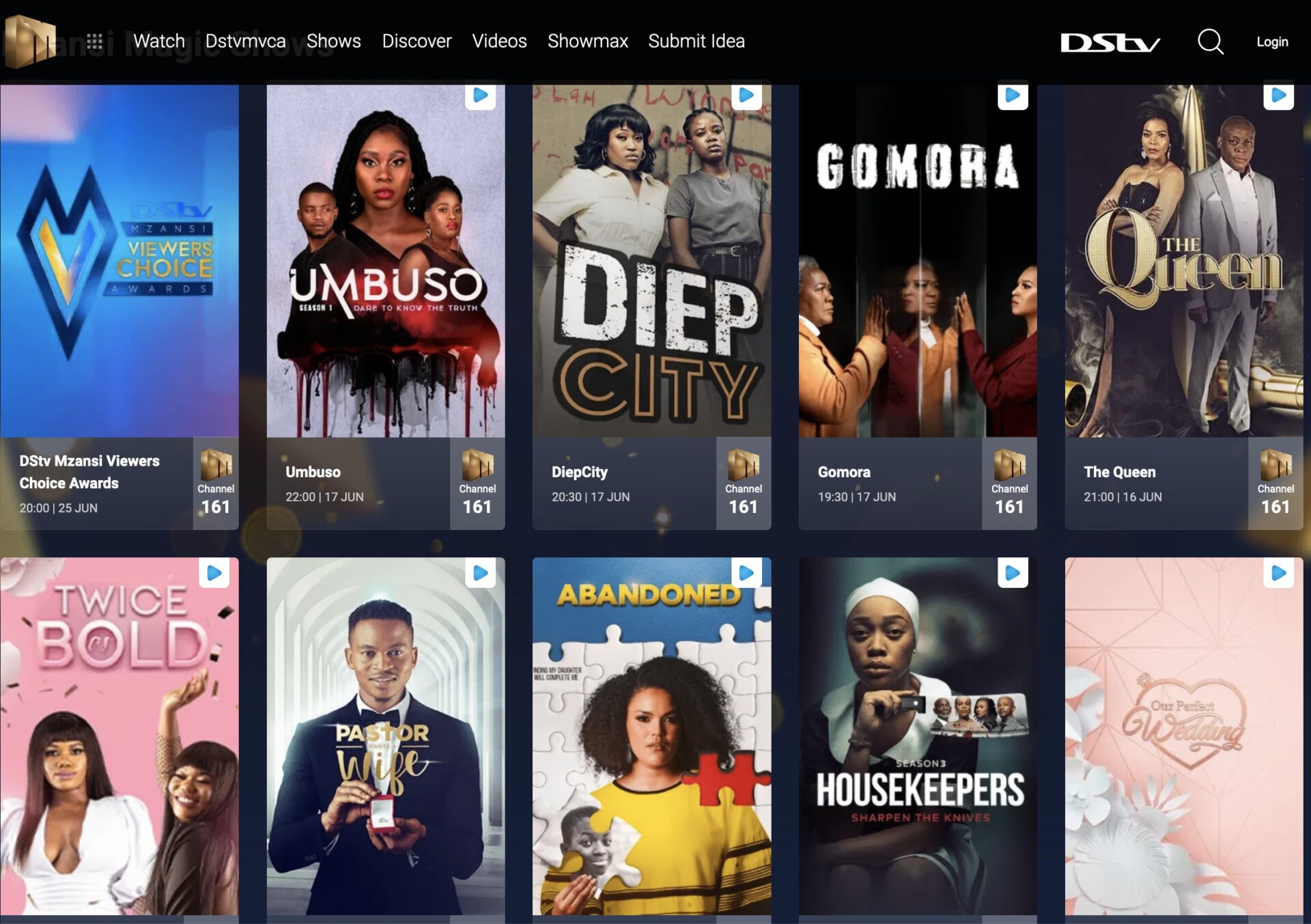

Perhaps it is a matter of definition, that is, was South Africa a transnational TV nation if it did not export content? But the case of South African television and its international shows is still different to the picture painted in the Aarhus course about Nordic television and raises so many questions. So, maybe the advent of streaming makes transnational currents speedier and more visible, but I wonder how many other nations and former colonies have a similarly transnational TV-watching culture that dates back to their early days of national (?) television. The fact that television in South Africa has always been transnational means that our ideas about the world and about ourselves have been influenced by what we have seen from around the world. In the South African context this becomes an identity conundrum as white people were more likely to have TV sets, while Black people less so, and because shows were produced and bought to entertain and inform some of the population in English, while others were unable to understand these shows. Today our television environment continues in a similar way with local satellite channels targeting black audiences – as I gather from this screenshot of the landing page of MzansiMagic (figure one).

Fig. 1: Landing page of DSTV’s MzansiMagic platform

Of course, black audiences are free to watch other channels and subscribe to other platforms, just as white audiences are free to watch these shows on MzansiMagic. Whether or not any white South Africans watch any of those shows is a topic for audience research and questions of integration. Notwithstanding the fluid nature of identity, a further question is how this continuation of separate platforms for different races affects our ideas of South Africanness. Do we need separate channels because of apartheid’s legacy, or do we maintain apartheid’s legacy with separate racialised channels? So many questions, so little time. Will my research shed some light on any of these questions?

Tina-Louise Smith has her Master’s in Film and Television Studies from the University of Cape Town. Her PhD research explores how crime fiction formats developed in the global north influence narratives and representation in South African crime shows within the very different South African context.

References

Bevan, C. 2009. Putting up screens: A history of television in South Africa, 1929-1976 (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria).