Steven Zaillian’s Ripley (2024), available on Netflix, arrives with the familiar signals of prestige adaptation: a canonical literary source (Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley), European locations, meticulous production design, and a controlled tonal palette. Yet one of its most distinctive features is not narrative content but tempo. In a streaming landscape structured by acceleration — rapid editing, plot density and reiteration, the perpetual demand for attention — Zaillian’s miniseries advances by extending and lingering. Scenes stretch, gestures repeat, and suspense takes shape less through escalation than through delay. Ripley does not simply feel slow: it makes slowness an organising principle.

The third episode, “III Sommerso”, offers an example in the sequence of Dickie’s murder. Rather than staging the killing as kinetic violence — rapid cutting, emphatic music, the usual grammar of shock — Zaillian and his collaborators let it unfold with chilling steadiness. The murder and its aftermath, especially Ripley’s attempt to cover his tracks, arrive not as spectacle but as duration: bodies arranged in space, time stretching before the decisive act, and the aftermath lingering long enough to become their own narrative unit. The effect is not only dread, but a shift in suspense. Here suspense comes less from what the viewer does not know than from what the viewer is made to stay with. Ripley forces us to inhabit the time of crime — preparation, instants, consequences, concealment, even imaginings.

A distinction matters here. Slow-TV (often hyphenated) has a specific meaning in broadcasting studies: long, uninterrupted, non-scripted, real-time programmes, often transmitted live or “as-live”, where duration becomes the event — for example, extended train journeys or scenic voyages shown minute-by-minute.[1] This is not what Ripley does. By contrast, slow television, as an analytical category, operates closer to slow cinema: scripted narrative works that adopt a deliberately decelerated aesthetic, marked by long takes or long sequences, reduced narrative density, and a reorientation of attention toward atmosphere, texture, and observation rather than constant plot advancement.[2] Zaillian’s Ripley belongs to this latter tendency. It is slow not because it is unedited or non-fictional, but because it constructs meaning — suspenseful meaning — through withholding, duration, and the discipline of looking.

Crime television typically treats time as something to compress. Investigation, concealment, and pursuit are tightened through quick cutting and narrative efficiency. Ripley repeatedly does the opposite. It lingers on processes: bodies moving through space, the work of tidying and concealment, the detailed maintenance of an invented identity, the presence of daily objects, the contemplation of paintings, and the presence of sculptures. In this respect, Ripley makes duration significant, shifting attention from plot to the marginal elements of undramatic style — texture, gesture, atmosphere, waiting.

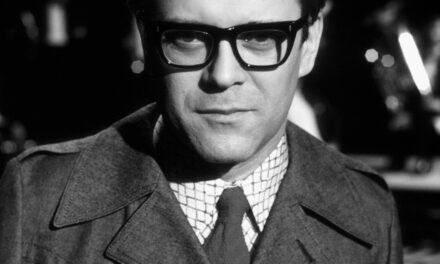

Tom Ripley (Andrew Scott) sits at the bow after murdering Dickie, head lowered and gaze downcast, framed by the open sea and overcast sky as he contemplates what to do next.

The murder sequence in the third episode is crucial because it shows how Ripley turns a potential genre peak moment into durational experience.[3] The sequence does not rush to the point. The miniseries does not rush to the point. Instead, it holds the viewer inside the uneasy temporality that precedes and follows violence: a threshold crossed, tension sustained, no quick payoff. When the act comes, it is not framed as catharsis. The miniseries stays with its consequences — contemplating the next move (fig. 1), the effort of handling the anchor weight, the weight of the corpse, the stubborn presence of matter, the mishaps, the struggle to sink the boat, the time it takes for the world to discover it. What another crime drama might compress into efficient beats becomes an extended confrontation with the labour of murder: not only the act, but the time after it, when concealment becomes routine and killing becomes mechanical.

In Ripley, slow television becomes an epistemological strategy. It refuses immediate clarity, not through obscurity, but by making knowledge itself durational. Comprehension arrives through the gradual accrual of detail, inference, and unease. This matters in a narrative where deception is not merely a plot device but the protagonist’s mode of being: identity is performed, and performance takes time.

Ripley’s black-and-white cinematography intensifies this aesthetic. Monochrome evokes neo-noir aesthetics, but it also functions as a perceptual regime. By reducing the immediate affective information colour provides, it redirects attention toward texture, contrast, surface, and spatial depth. It slows the viewer’s looking. This is not only a matter of style, but of spectatorial discipline: the series guides its audience to watch carefully rather than quickly.

Noir’s aesthetics of obscurity and partial legibility is well established. Shadows, oblique angles, and high-contrast lighting do not merely create mood: they produce uncertainty.[4] Ripley extends this tradition into a contemporary serial form, aligning visual ambiguity with narrative delay. Its emphasis on architectural framing — corridors, staircases, thresholds, windows — turns space into a container for time. Characters appear held in place, as if the world itself were structured around waiting.

This visual discipline has ethical consequences. Slow cinema criticism often argues that slowness can function as an ethics of attention, compelling viewers to engage differently and more creatively with time and the human figures on screen.[5] Ripley adapts this ethical dimension in a darker register. Its slowness invites contemplation as well as produces involvement. We remain with Ripley long enough that deception begins to look like habit. The longer we watch, the more clearly moral horror appears as something that can be normalised through repetition and time.

It might be tempting to frame slow television as an alternative to narrative intensity. Yet Ripley proposes something more paradoxical: a thriller whose vividness is generated not through speed and agitation, but through slowness and stillness. The result is a form of noir attuned to the contemporary politics of attention — one that makes watching feel less like consuming and more like enduring.

Sérgio Dias Branco is Associate Professor of Film Studies at the University of Coimbra and a researcher at CEIS20 – Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies at the same institution. He has taught at Nova University of Lisbon and the University of Kent, where he was awarded an MA and a PhD in Film Studies with a thesis on the aesthetics of television fiction series. His research and publications encompass film, television, and media theory, including studies on the aesthetics and attentive viewing of television series and critical writing on television narratives and style, alongside broader work in cinema, religion.

References

[1]. On “slow-TV” as a distinct broadcast phenomenon — characterised by long, uninterrupted, non-scripted, real-time programmes — see Elisabeth Morney, “Creative Prerequisites for Innovation in Group Collaboration — A Case Study of Slow-TV, the Genesis of a Norwegian Television Genre,” Journal of Creativity 32, no. 3 (2022), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2713374522000140.

[2]. See Matthew Flanagan, “Towards an Aesthetic of Slow in Contemporary Cinema”, 16:9 (2008) and Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge (eds.), Slow Cinema (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016).

[3]. This also applies to Freddie’s murder sequence in the fifth episode, “V Lucio”.

[4]. See James Naremore, More Than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998; rev. ed. 2008), 26.

[5]. See Ira Jaffe, Slow Movies: Countering the Cinema of Action (London: Wallflower Press, 2014), 8.