British television re-started after the Second World War on 7 June 1946, with programmes that included adaptations of theatre dramas, and relays of public ceremonies and sporting events. It relied heavily of remediation, Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin’s (1999) concept of remaking or repurposing meanings from one text into another but also the extension of a text across multiple mediums and platforms. Remediation can be thought of as a movement of return to an antecedent source, repeating it but in a different form. This implies a temporal sequence, of going back and starting again. The result can never be a pure return to the original, but instead repetition displaces the original and makes it function differently. We can think of each movement back to start again as a kind of looping or spiraling, which creates a temporal structure of then and now, and a spatial structure that positions one thing in relation to what it recapitulates or displaces.

I decided to blog about British television in 1946 because it is when television started again, rather than when it started first. Britain had the first television service in the world, launched by the BBC on 2 November 1936. The early programmes were broadcast to the tiny number of households in the London area that owned television sets. Most people viewed in private homes, and watching meant gathering together, in a semi-circle around the television set (and probably also around the fireplace). There is my motif of the loop or circle again, this time in the material space of the living-room.

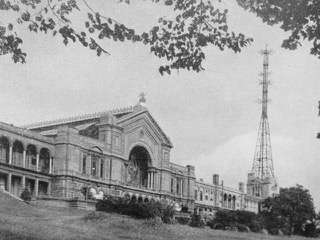

Early television was characterised by a geographical notion of radial extension, where a central source radiates out to a heterogeneous hinterland. The television service had closed down on 1 September 1939 because of the outbreak of war, and among the reasons cited was that radiating signals from the Alexandra Palace transmitter provided a fixed compass point that could be used by enemy bombers. After the end of the Second World War in 1945, more than a million homes and many public buildings had been destroyed or damaged in London. Reconstruction involved restarting television broadcasting operations, alongside the much more established radio services, as part of the effort to reconstitute national culture. Television, like radio, was intended to draw Britons back together within the circles formed by their signals.

At the centre of BBC TV were Alexandra Palace studios, equipped for programme production and also dissemination from the huge rooftop aerial. In 1946, months of effort went into repairing and refurbishing cameras and transmission equipment, costumes and scenery, and surviving staff from before the war were reappointed. The BBC Year Book of 1947 reflected that the apparatus worked better than in 1939; this was a return, but with a difference.

Programmes began with a varied schedule that included a formal opening ceremony, ballet with Margot Fonteyn, a Mickey Mouse cartoon, music from Geraldo and his orchestra, and an adaptation by the head of drama Michael Barry of a French short story, The Silence of the Sea, about the French wartime Resistance. Next day, much of the schedule was taken up with live coverage of the Victory Parade, in which military personnel marched through London in the presence of the King, Queen and Princesses.

Television radiated out across London, in a circle of about 40 miles radius. To go beyond the studio, the BBC used two Outside Broadcast units. Within the city, a direct physical connection with the studio could be established by plugging the OB unit into a huge co-axial cable that had been laid, encircling London’s West End. This ring of cable demonstrated physically how London-centric the television service still was; television would be most interested in the things that could be seen within that metropolitan space. The circle encompassed the premier locations associated with government, royalty, religion, theatre, ballet and opera, and of course the BBC’s own headquarters. This was the charmed circle at the heart of Britain and its Empire.

Television was expected to relay things that would have happened anyway (like parades, West End plays or tennis matches), but remediation would transform them because of their new-found accessibility (Scannell, 1990). BBC Television physically placed its cameras within the audiences that encircled major events. In West End theatres, cameras were positioned on the Dress Circle at the Garrick and His Majesty’s theatres, for example, to relay current shows. OB cameras followed the circling couples at the Hammersmith Palais de Danse and in the circular auditorium of the Royal Albert Hall. BBC transmitted pictures by remote radio links between its OB vans and Alexandra Palace, to watch the motorcycles repeatedly roaring around the circuit of Wimbledon Speedway and to see matches at the Oval cricket ground. At Alexandra Palace itself, dancers from the New York Ballet spun around the small studio. More and more circles.

The sending-out that broadcasting involves is matched by the intention for society to get something back. The action of broadcasting is a loop, reaching out to the audience and embracing it. In 1946, television transmission and reception had a single form. Centrally-generated broadcast signals were received by a mass audience situated in a different physical space. The audience was imagined as a large public group, and John Durham Peters (1999: 210-11) describes the ideals of broadcasting as ‘visions of the agora, the town meeting, or the “public sphere”’. But the audience was nevertheless atomized, comprising small groups watching their television sets in the 40-mile circle surrounding London. Spatially, viewers were positioned as a destination or receiver but they could not speak back; television was one-way and the loop of communication could not be closed. I think there are so many rings, circles, loops and spirals woven into the history of early television because television unconsciously thematized the tensions at the heart of broadcasting. Broadcasting entails both inclusion and exclusion, sending and receiving, creating and remediating. As it sought to find itself, it moved forward by going around in circles.

Jonathan Bignell is Professor of Television and Film at the University of Reading. His writing about television, film and toys is listed on this web page. Some of it can be downloaded freely in Open Access from there and other material is available from Academia.edu. A longer version of this blog was presented at the 2015 Association of Adaptation Studies conference in the School of Advanced Study, University of London, in 2015.