The original line of this opening was: ‘It might seem odd to devote a television blog to books’; however, following Billy Proctor’s blog last week it now feels almost like bandwagon jumping. For me, though, the two media have always been closely intertwined. The first and most obvious connection is the huge role the literary adaptation has played in the history of television drama output, here in Britain at least. Looking at the fiction section of my bookcase (it’s highly compartmentalised, of which more anon), I note that it is dominated by authors whose works were arrived at in my formative years via TV versions. Austen, Dickens, Graves, Priestley, Waugh, Welles, Wodehouse, Wyndham, Winterson (Jeanette) – yes, alphabetised by surname, unlike so many of my undergraduates’ bibliographies – are all present and correct thanks to an initial small screen inspiration. My Tolkien collection, for example, exists entirely as a result of seeing The Hobbit in a Jackanory (BBC, 1965-96) group reading back in 1979: Jan Francis narrated, Bernard Cribbins was Bilbo, Maurice Denham (with that voice to die for) read Gandalf, and David Wood made a superbly slimy Gollum. Enthused, I purchased both this book and The Lord of the Rings, through which I determinedly ploughed at the tender age of nine. I’m not sure how much of it I truly appreciated at the time (though I still had David Wood in mind when reading the Gollum sections), but this herculean endeavour was all due to television, and I honestly doubt whether I would have been moved to similar efforts by Peter Jackson’s big screen versions two decades later.

Some television programmes don’t immediately spring to mind as having been adapted from novels. Did you know, for example, that the first series of The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin (BBC, 1976-79) was based on David Nobbs’ 1975 novel, The Death of Reginald Perrin? As sterling television academics, you probably did; but were you aware that, while no less great (or, indeed, super) than its twin, the original book featured some far earthier storylines, including an incest-based sub-plot for Jimmy (Geoffrey Palmer, for goodness’ sake!) and Linda, Reggie’s brother-in-law and daughter? Strong meat indeed for anyone who thrived solely on the catchphrase-based humour of the television series…

I didn’t get where I am today by reading about incestuous relationships between sitcom characters.

Whether one could really call The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (BBC, 1981) a literary adaptation is debatable, the radio series (which I still haven’t heard) having pre-dated the book, both of which arrived before the TV version. This is, however, another example of television providing the entrée to a much-loved author. In fact, returning my gaze to the bookshelves for a moment for inspiration, the only name that leaps out as not having been significantly televised is Isaac Asimov. Some of his work was used for Out of This World (ITV, 1962) and Out of the Unknown (BBC, 1965-71), while the novel The Caves of Steel received a 1964 adaptation for Story Parade (BBC, 1964-65) – starring Peter Cushing, no less – but his robot/Empire/Foundation stories would provide excellent material for an on-going series of serials. Anything Game of Thrones (HBO, 2011- ) can do, Asimov could do so much better.

As a youth, my television-inspired reading wasn’t limited to works which had been transferred to the small screen. In fact, the majority of it probably consisted of what would now be termed TV ‘tie-ins’; books whose content derived from television, rather than having provided source material for the screen. These can be divided into two categories: ‘making of’ volumes (full of fascinating facts for the aspiring television scholar), and novelisations of television series and serials; adaptations in reverse, if you will. In my early adolescence I spent the majority of my pocket money on the latter, only turning to those ‘behind-the-scenes’ tomes in my late teens, when my reading habits began to be fuelled by an interest in the production context of television which continues to the present day.

Alas, not many of these old TV novelisations have made their way onto my modern bookshelf, and the majority now lie disregarded at the back of a cupboard in my parents’ house. Leafing through their pages today, it is clear that few were significant works of art, due largely, I believe, to the fact that they were not often penned by the authors of the television originals. Fred Taylor’s workmanlike adaptations of the first two series of Auf Wiedersehen, Pet (ITV, 1983-84; 1986) added little to Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais’ dialogue, and I recall feeling somewhat short-changed when a series two episode in which Oz attempts to reconnect with his son was glossed over with a single paragraph.

Given the choice today between reading these books and watching a pristine DVD copy, many would inevitably opt for the latter, and it was arguably the proliferation of home media that spelt the end for this particular spin-off market; a point I shall return to shortly. However, not all ‘old’ TV has since been made readily available on VHS, DVD and BluRay, and for some programmes the yellowing pages of my once-treasured novelisations are all I have to remember them by. Prime examples include Stella Bingham’s Charters & Caldicott, ‘from the BBC TV serial by Keith Waterhouse’ (1985), which took the cricket-obsessed gents of The Lady Vanishes (Hitchcock, 1938) and plunged them into a post-retirement murder mystery, deliciously essayed on the screen by Robin Bailey and Michael Aldridge over six episodes.

Better still was The Dark Side of the Sun (BBC, 1983), the supernatural thriller by Michael J. Bird. A prolific and respected television writer in his day, Bird’s name is seldom mentioned in television studies. However, his work in the 1970s and early 80s was, I would argue, just as popular as that of more lauded contemporaries like Alan Plater and Dennis Potter, and is equally worthy of study. Arguably his last big popular success, The Dark Side of the Sun continued the lavish (for the time) use of Mediterranean locations which formed the backdrop to so much of Bird’s work, and centred around a young widow, Anne Tierney (Emily Richard), who begins seeing the image of her late husband, photographer Don (Patrick Mower), wherever she goes. She grows convinced that he is trying to contact her from beyond the grave, and the hauntings continue when she travels to Rhodes, where Don died in mysterious circumstances. Here she encounters businessman Raoul Lavalliere (Peter Egan); a suave nobleman who is hiding a dark secret… It was charming, picturesque and nonsensical, probably; more memorable for the exotic locales and haunting score than its labyrinthine plot. As with much of Bird’s work, a DVD release has not been forthcoming,[1] and until some brave soul at an enterprising company like Network decides to take a gamble on The Dark Side of the Sun (Special Edition), the novelisation – for which Bird shares his authorial credit with Hugh Miller – is the nearest we can get to re-experiencing it. Programme and book made such an impression on me in my youth that I also purchased the Stavros Xarhakos soundtrack, the cassette of which has, sadly, long since worn out. Many years later I even chose to spend my honeymoon on Rhodes, though I didn’t become entangled with any Greek demons masquerading as a reincarnated Knight Templar (admit it; you’re intrigued, aren’t you?).

Better still was The Dark Side of the Sun (BBC, 1983), the supernatural thriller by Michael J. Bird. A prolific and respected television writer in his day, Bird’s name is seldom mentioned in television studies. However, his work in the 1970s and early 80s was, I would argue, just as popular as that of more lauded contemporaries like Alan Plater and Dennis Potter, and is equally worthy of study. Arguably his last big popular success, The Dark Side of the Sun continued the lavish (for the time) use of Mediterranean locations which formed the backdrop to so much of Bird’s work, and centred around a young widow, Anne Tierney (Emily Richard), who begins seeing the image of her late husband, photographer Don (Patrick Mower), wherever she goes. She grows convinced that he is trying to contact her from beyond the grave, and the hauntings continue when she travels to Rhodes, where Don died in mysterious circumstances. Here she encounters businessman Raoul Lavalliere (Peter Egan); a suave nobleman who is hiding a dark secret… It was charming, picturesque and nonsensical, probably; more memorable for the exotic locales and haunting score than its labyrinthine plot. As with much of Bird’s work, a DVD release has not been forthcoming,[1] and until some brave soul at an enterprising company like Network decides to take a gamble on The Dark Side of the Sun (Special Edition), the novelisation – for which Bird shares his authorial credit with Hugh Miller – is the nearest we can get to re-experiencing it. Programme and book made such an impression on me in my youth that I also purchased the Stavros Xarhakos soundtrack, the cassette of which has, sadly, long since worn out. Many years later I even chose to spend my honeymoon on Rhodes, though I didn’t become entangled with any Greek demons masquerading as a reincarnated Knight Templar (admit it; you’re intrigued, aren’t you?).

The extent to which Bird contributed to this particular novelisation is uncertain, but like several of his peers he usually took pains to handle writing duties for the book versions of his work, penning the print releases of Who Pays the Ferryman and The Aphrodite Inheritance solo. Alan Plater was another TV scribe who seemed to enjoy fleshing out his television serials in novel form. The pleasure of reading his Beiderbecke books derives from the knowledge that the author had actually originated the characters whose exploits he was essaying, meaning insights were provided that could only be hinted at in the televised version.

In the case of Terry Nation’s Survivors novel, the author had a particular axe to grind, having spectacularly fallen out with the producer of the television series, Terence Dudley. Radically re-imagining several of the characters and situations he had penned for his first-season episodes (after which he walked away from the production), Nation’s book is far more indicative of the bleak direction in which he had wanted the programme to head. Featuring a grimly ironic conclusion to main character Abby Grant’s search for her missing son (I won’t spoil it for you, but it doesn’t end well), the book version of Survivors stands up rather well as a work of fiction in its own right, some sections strongly evoking the post-apocalyptic atmosphere of The Day of the Triffids.

Two other TV-inspired books which still very much hold their own are Andrew Davies’ adaptations of his splendid satire on the modern university, A Very Peculiar Practice (BBC, 1986; 1988), about which I held forth in a previous blog. Like Plater’s work, Davies’ novelisations added flesh to already compelling characters, with the bonus that pre-watershed expletives were no longer deleted (always appealing to a teen reader). As a special, meta-textual treat, Davies included a brief coda to each episode/chapter, in which the experiences of his literary alter ego, Ron Rust (played on screen by Joe Melia), were related as he struggled to pull the series together, meeting with (real-life) director, David Tucker, producer, Ken Riddington, and Head of Series and Serials, Jonathan Powell. Read today, these vignettes provide a bleakly humorous account of pitching and scripting a television drama in the glory days of Television Centre,[2] while becoming increasingly inter-woven with the story proper after Rust decides to include himself in the serial. Such witty post-modern touches went far beyond the usual limits (and limitations) of a television novelisation, and it is fitting that, in light of his later (and, in my opinion, lesser) TV career adapting the classics, Davies’ tomes would now stand immediately next to Dickens on my shelf were it not for the presence of Gulliver’s Travels (always arrange alphabetically by author surname, remember).

Two other TV-inspired books which still very much hold their own are Andrew Davies’ adaptations of his splendid satire on the modern university, A Very Peculiar Practice (BBC, 1986; 1988), about which I held forth in a previous blog. Like Plater’s work, Davies’ novelisations added flesh to already compelling characters, with the bonus that pre-watershed expletives were no longer deleted (always appealing to a teen reader). As a special, meta-textual treat, Davies included a brief coda to each episode/chapter, in which the experiences of his literary alter ego, Ron Rust (played on screen by Joe Melia), were related as he struggled to pull the series together, meeting with (real-life) director, David Tucker, producer, Ken Riddington, and Head of Series and Serials, Jonathan Powell. Read today, these vignettes provide a bleakly humorous account of pitching and scripting a television drama in the glory days of Television Centre,[2] while becoming increasingly inter-woven with the story proper after Rust decides to include himself in the serial. Such witty post-modern touches went far beyond the usual limits (and limitations) of a television novelisation, and it is fitting that, in light of his later (and, in my opinion, lesser) TV career adapting the classics, Davies’ tomes would now stand immediately next to Dickens on my shelf were it not for the presence of Gulliver’s Travels (always arrange alphabetically by author surname, remember).

I’m sure that thought would please him.

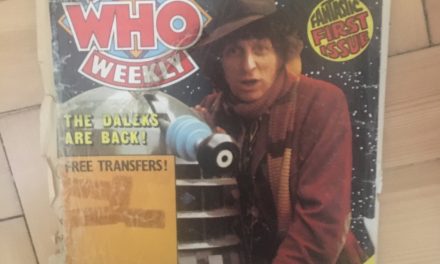

By the time Davies’ books came along I was beginning, in my late teens, to move beyond the series which had comprised by far the largest portion of my adolescent reading: W.H. Allen’s Target imprint, which focused almost entirely on novelisations of Doctor Who (BBC, 1963-89). If, like me, you are a television academic of a certain age (not too young, but not too old), you probably spent many an hour in the school library leafing through these print versions of the Time Lord’s adventures. The first book I bought was Doctor Who and the Image of the Fendahl (they always added an ‘and’ to the title until the early 80s; Doctor Who and the Snakedance wouldn’t have sounded right) in 1979. I don’t think this is one of the most distinguished books in the range, and, at 109 pages, it is certainly one of the shortest, but it was written by Terrance Dicks, and that’s what counts. Doctor Who’s script editor throughout the Jon Pertwee era, Dicks was already thinking of leaving the programme when Target launched the book range in 1973, and soon became unofficial series editor. After three previously-published books from the 1960s had been re-issued (complete with beautiful new covers by Chris Achilleos), it was down to Dicks to kick-start the series, both writing adaptations and apportioning stories to other writers. Although he quickly roped in some old Who hands to help out – Gerry Davis, Brian Hayles, Malcolm Hulke, Barry Letts and Philip Hinchcliffe all doing their bit – the lion’s share of the work increasingly fell to Dicks, and by the end of the decade this was perhaps taking its toll on the quality of his output. However, even a brisk novelisation like Fendahl contains some extremely atmospheric opening up and embellishing of the television script. Dicks’ description of the hitch-hiker who falls victim to the (as yet unseen) monster early in the first episode caused me many a childhood nightmare, and as for finishing Doctor Who and the Horror of Fang Rock last thing at night (and then having to get out of bed to turn off the bedroom light)…

Unwise; very unwise.

One of the many joys of reading Dicks’ books was anticipating his stock descriptions of the various Doctors. Jon Pertwee had a ‘young-old face’ and ‘a mane of white hair’; Tom Baker jammed ‘a soft, broad-brimmed hat’ onto ‘an unruly mop of curls’; and Peter Davison had ‘a pleasant, open face’. FYI, Hartnell usually also had a mane, and Troughton a mop. This was good, reliable stuff.

Actually, my preferred writer in the series was Ian Marter, who had earlier played Harry Sullivan on screen to the fourth Doctor. His books were regarded as more ‘adult’ because he didn’t shy away from violence, and even added the word ‘bastard’ to Doctor Who and the Enemy of the World (boy, was I glad my mum didn’t catch me reading that). He also added a more visceral touch to his descriptions; in Marter’s books, companions were always recoiling from the rank breath of Sontarans, or the oily vapours emitted by Cybermen.

Sadly, I don’t have shelf space for these books here in my London Hobbit-hole, but if I did I would have no qualms about openly displaying my Target library (and they did refer to it as such). These books not only helped improve and expand my vocabulary during school years (I began slipping words like ‘voluminous’ and ‘capacious’ into my English Language short stories after reading descriptions of the Doctor’s pockets), they allowed me to retain and own my favourite show in permanent, physical form; to hang onto and re-experience the programmes – even some I’d never seen, and wasn’t ever likely to (or so I thought) – at a time when repeats were few, the constant re-runs of modern-day nostalgia channels like Drama an undreamt-of luxury. Although in the early 1980s pre-recorded video cassettes (VHS or Betamax; which to invest in?) were becoming available very, very slowly (or so it felt), these were still prohibitively expensive. It was only in 1986 that I excitedly purchased my first Doctor Whovideo, when ‘Revenge of the Cybermen’ magically appeared in Woolworths for something like £8.99. It was more expensive than a book, yes, but ridiculously affordable for a home video. What’s more, this was the real thing; a copy I could keep and re-watch for ever and ever…

Well, times change. That purchase marked the beginning of the end for my novelisation fever, though I persisted with Target until the end of 1987, when the arrival of Sylvester McCoy heralded a whole new era of disillusionment. It was at that point I started gravitating more towards factual, ‘making of’ books, several of which had already been added to my Doctor Who collection. The heyday of these publications was probably the 1990s, when even the repeat screening of an archive programme could result in a celebratory print spin-off, Geoff Tibballs’ Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased) (with a foreword by Kenneth Cope) offering an excellent example. Rather than being a simple TV listings cut and paste job, these publications actually featured new material: interviews, photographs, and behind-the-scenes information, which today provide a valuable resource for historians and students interested in researching television productions and companies whose (written) archives are often less well preserved or accessible than, say, those of the BBC. To return to my bookshelf, I now have an entire row devoted to TV tie-ins (non-fiction), arranged alphabetically by programme title; this comes immediately before the biography section, which is of course arranged alphabetically by subject surname.

I told you it was highly compartmentalised.

However, if the coming of VHS sounded the death knell for the TV novelisation, DVD could be said to have dealt a similar blow to the ‘behind the scenes’ tie-in volume from the 2000s onwards. The plethora of cast interviews and ‘making of’ featurettes that populate modern DVD and BluRay releases have in recent years made the good offices of publishers like Boxtree a somewhat redundant enterprise. Only the really big guns like Doctor Who now seem to regard a secondary literary market as something worth investing in, and the programme’s anniversary year saw the release of a vast number of celebratory volumes, on which I am happy to say I spent not one penny. Who wants to get lost in something called The Vault? If it isn’t by Peter Haining, I’m not interested.

TV tie-ins today seem to be primarily comprised of graphic novels and computer games; alternate fictions, and transmedia storytelling. It all sounds rather demanding, and besides; the majority of my reading is now work or research-related. This of course means that I am, happily, still focusing on television much of the time, at least. And while there are occasions when I would prefer to be searching for the latest Target novelisation in W.H. Smith, all things considered I suppose I really can’t complain.

Happy holiday reading, everyone!

Dr Richard Hewett teaches television and film at Royal Holloway, University of London. He completed his PhD, Acting for Auntie: From Studio Realism to Location Realism in BBC Television Drama, 1953-2008, in 2012 at the University of Nottingham, and has since contributed articles to The Journal of British Cinema and Television, The Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television and Critical Studies in Television. Full details of publications can be found here.

[1] The excellent Who Pays the Ferryman (BBC, 1977) is at least now available here in Britain, while the somewhat less excellent Maelstrom (BBC, 1985) can be found in Norway, of all places.

[2] When I interviewed Jonathan Powell for my PhD, I showed him – just for fun – Davies’ fictionalised account of his reaction to the original series pitch: ‘“Let’s do it,” [Powell] says. Then he smiles at Rust. “Heaven on wheels. Just needs writing.”’ (Davies 1986: 73). ‘I did say that,’ he affirmed enthusiastically; ‘I did say “Heaven on wheels”.’ There’s a little piece of history for you.