It’s marking madness right now, chaps. Staff usually have fifteen working days from assessment submission dates to get grades and feedback up on the Virtual Learning Environment, but as a result of the current situation students have had their late window trebled to twenty-one consecutive days. This means that the tardier submitters, who would normally have got their work in two weeks ago (allowing me to turn it around in good time for the post date), are even as I write still making those final, painstaking tweaks to carefully prepared reference lists, doubtless ensuring they have included page numbers for any and all direct quotations from a print source in their in-text citations prior to the 4 pm cut-off.

Well, I can hope, can’t I?

I’ve marked everything on my second and third year modules, but there are still the first year essays to get through, plus moderation of colleagues’ courses, and tbh [1] it’s all feeling a little Sisyphean right now.

Will the line stretch on to the crack of doom?

Time to take a break from sweeping water up the hill – but what am I to blog about? Should I muse upon what the COVID-19 crisis could mean for HE? Or write about what I’ve been up to during lockdown? Well, I’ve been getting my head around online teaching, doing a sod of a lot of marking, and trying not to get stressed, basically. I don’t sleep as well as I could, but that’s the worst I can complain of, so I’m lucky. The campus closures forced upon us by lockdown have produced some interesting ironies, at least. All those middle manager types (and, even worse, the would-be middle manager types) who usually invest their energy in making snarky comments whenever theory staff dare to make use of their research allocations have suddenly bought into the ‘Hey, we can do it just as well from home’ philosophy with all the zeal of Saul of Tarsus en route to Damascus. My department has always promoted its courses primarily on the basis of its physical location in MediaCityUK, its state of the art recording and editing equipment, and the industry contacts and work placement opportunities it offers to students.

Fat lot of good those are right now.

If only potential customers could instead be sold on the concept of stimulating, well-taught didactic content that provides a solid grounding for original thought and independent research.

Nah.

It would never catch on.

I am extremely fortunate to have spent lockdown in a place that has been close to my heart for most of my adult life: the north London Edwardian suburb of Muswell Hill. I’ve blogged before about my passion for Muzza, as my partner calls it, and the attraction has not lessened despite not being able to leave for the last three months. Since first moving to our glorious capital a quarter of a century ago I have lived at no fewer than five addresses, each within a mile of each other in the N10 postcode. Exciting job opportunities have from time to time dragged me away (teaching in such glamorous spots as Piedmont … Rome … and Salford), but I have always ended up gravitating back here – this time for keeps, I think. And if I have to be stuck anywhere in these uncertain times©™, there is no place I would rather be stuck.

Muswell[2] Hill[3] has three notable media connections. As home to Alexandra Palace (or Ally Pally, as we locals are allowed to call it), it is the official birthplace of British television, dating from the BBC’s regular ‘high definition’ (for the time, that is) broadcasts in November 1936. You probably know all about that, but if not then Bruce Norman’s Here’s Looking at You: The Story of British Television 1908-39 (1983) provides a lovely, evocative account of those initial pre-war broadcasts. This was back when TV was Good For You, and the most frivolous item you could pick up if you were lucky enough to own a set (and be within range of a transmitter) was Picture Page; the One Show of its day.

Until very recently there was a pub in Muswell Hill on Fortis Green Road called The John Baird, named after the Scot credited with the invention of television – despite the fact that his transmission system was swiftly mothballed by Auntie Beeb in favour of Marconi-EMI’s. With truly unfortunate timing, this hostelry – which is built on a WWII bomb site – was refurbished and rebranded as The Village Green just a few weeks before the virus hit.

Although Ally Pally was superseded by Lime Grove, Riverside and of course Television Centre in the 1950s and 60s, it did play home to one of the most significant productions in post-war British television history when The Quatermass Experiment was mounted there live in 1953. Around the time I was researching this production for my PhD, the Palace threw open its doors to the old television studios (now roughly stripped of the asbestos that once lined the walls) for one glorious weekend only, and I got to look through the viewfinder of the type of Emitron camera that would have been used on the original production – complete with upside-down image.

I must admit that this sent a shivery frisson of excitement down my spine – but then I don’t get out much, even when I’m not on lockdown.

Ravaged by fire (for the second time, as it happens) in 1980, and abandoned even by the Open University from 1981, Ally Pally has probably burned a large hole in the pockets of Haringey Council over the years – but we wouldn’t be without it. Under normal circumstances, I think it is most frequently visited these days for its ice skating rink, but last year there were signs of further renewal when the old Victorian Theatre finally reopened, and those of us who care about such things are very glad that it has not been demolished (like Lime Grove), or turned into luxury flats (for shame, TVC; for shame).

As the charity webpage puts it, we can’t imagine a world without Ally Pally, and on those occasions when I have ventured out for permitted exercise over the last few months, the yomp up the hill has provided my favourite walk. Even though the building itself is closed, the park still offers some of the most stunning views in London.

Cue deep, contented sigh.

OK, so you probably knew about the TV connection. But hands up how many people were aware that Muswell Hill also gave birth to the UK’s greatest ever band, the Kinks? Brothers and founding members Ray and Dave Davies grew up down the road in Fortis Green before rampaging into the pop charts with such proto-metal singles as ‘You Really Got Me’ and ‘All Day and All of the Night’ in 1964, and the locality has since loomed large in their song-writing careers, even providing the inspiration for the 1970 album (one of their best), Muswell Hillbillies (why not listen to it illegally here? And then actually buy a copy, because it’s really good?). Since moving back to the area I have seen both Ray and Dave (who, after years of bickering, have actually moved next door to each other) out and about in neighbouring Highgate (which also has some breath-taking views of London). The Kinks’ studio, Konk, which has been their creative base since 1973, is down the road in Hornsey, on the way to Wood Green. [Editor’s Note: Konk is actually in Hornsey which means that Richard takes a long way round to get to Wood Green!! And I actually bumped into Ray Davies at the newsagent at the end of our road one day – that shows how close it all is].

The Kinks’ career, which spanned their first recording contract in 1963 to their final live performances together in 1996, forms a mini-history of pop music on British television. In the 1960s they played all the big shows, from Ready, Steady, Go! (ITV, 1963-66) (on which they debuted their first single, a cover of ‘Long Tall Sally’ – and a notorious flop), through the more rhythm-and-blues oriented Beat Room (BBC, 1964-65), and of course Top of the Pops (BBC, 1964-2006), for which most of their performances have since been lost. Then, in the 70s, they appeared on muso’s delight The Old Grey Whistle Test (BBC, 1971-88) and the more kiddie-friendly Supersonic (ITV, 1965-77), and squeezed in TV concert specials in 1972, 1973 and Christmas 1977, before focusing primarily on the US. 1983 saw the band make a slight UK return with the surprise hit ‘Come Dancing’ in 1983, which got them back on Top of the Pops for the first time since Ray poured beer over Slade in 1972. By this point the arrival of MTV meant that the pop promo was superseding poorly mimed studio performances as a means of getting product out to the pop pickers, but the band still put in a proper live appearance on The Tube (Channel 4, 1982-87) to promote the underrated ‘Lost and Found’ single in 1987. In the 90s the video for ‘How Do I Get Close’ popped up on Rapido (BBC, 1988-92) (does Antoine De Caunes’ ludicrous accent ring bells for anyone else? He must have been putting it on for the cameras…), and the band were honoured with a live turn on an early edition of Later… with Jools Holland (BBC, 1992- ) before coming full circle for one last blast of the power chords on TOTP2 (BBC, 1994-).

I have just discovered that in August 1990 the Kinks played a concert at Alexandra Palace, which neatly brings together two key strands of this blog. It’s a shame I wasn’t there, but that performance took place just two months before I made my first ever visit to Muswell Hill, to attend the inaugural Kinks Konvention (the unnecessary use of the letter ‘k’ has long been a Konceit of Kinks Kultists) at the Kommunity centre, down the slope and round the back of Marks and Spencer.

For a young Kinks fan (as I then was), it was a wondrous day indeed.

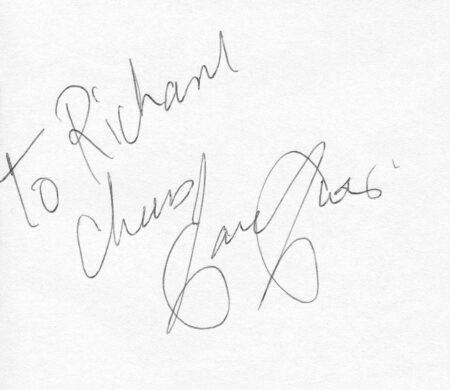

After a morning of quizzes, songs and mingling, attendees were thrilled to receive a visit from the latest line-up of the band (bar Ray) in the late afternoon, and I excitedly managed to grab lead guitarist Dave for a quick word and an autograph. With all the gauche earnestness of a nineteen-year-old devotee, I told him I had really enjoyed the positive atmosphere at the concert the band played at the Town and Country Club the previous year (my first ever gig; always a special one). ‘Yeah, it was nice, wasn’t it?’ Dave enthused. ‘Cheers, Richard.’

And that, friends, is what the great man wrote in my autograph book:

It was a magical moment of contact; you have probably already divined that. But still better was to come, with the subsequent arrival of Dave’s elder sibling, and frontman of the Kinks: Sir Raymond Douglas Davies.

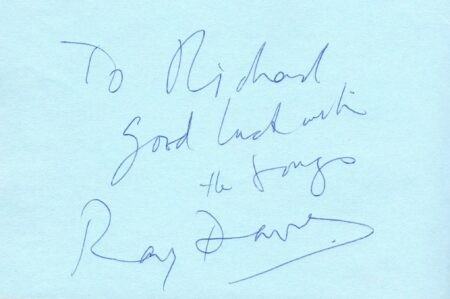

Patiently, the legend accepted obeisance from his admirers, and eventually my turn came. I told Ray how much I admired the opening track (‘Aggravation’ if you’re interested; it’s all about being stuck in traffic) of their last album (UK Jive; probably their best since Muswell Hillbillies. Listen here, then purchase), and how much I identified with it.

‘Really? That’s interesting,’ he conceded.

I then asked him to sign my little book:

Yes, I was writing. I could have been huge, you know. But then Damon Albarn came along and stole my thunder.

Ah, well. Britpop’s loss has proven to be academia’s gain, and maybe it is better this way.

Thus was a terrible beauty born, though it was another five years before I moved into the area. And then out. And then back again. And then out again, and back again… you get the picture.

But what, I hear you cry, about the third media connection with Muswell Hill that you mentioned earlier? You haven’t forgotten about it, have you? Not getting a little dotty after spending so much time in the flat?

Well, that’s quite some attitude. You never used to be so aggressive.

As it happens, I learned of this last connection nearly two decades after my initial visit, when I commenced my MA in The History of Film and Visual Media at Birkbeck College. It was the inaugural lecture, and Professor Ian Christie was enthusing at length about silent film, which is after all what he is paid to do. I was already interested, but became still more so when Ian revealed that, many years before its more famous television connection, Muswell Hill had in fact been the site of one of the first ever UK film studios, pioneered by the now-forgotten producer R.W. Paul.

So, there you are.

All creative paths, it seems, lead to this hilly little patch of north London: cinema, music, and of course TV.

And here I sit, in my little study, watching the 134 bus strain its way up Colney Hatch Lane towards the Broadway. At a time when not everyone is perhaps fortunate enough to be where they would wish, I’m grateful that, as long as some version of lockdown remains in force, I can stay here, in Muzza. Because, in the words of one of Mr Davies’ lesser-known songs, this is where I belong.

If only I didn’t have all this marking to get through…

Dr Richard Hewett is a lecturer in media theory. He has contributed articles to The Journal of British Cinema and Television (twice, actually), The Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television (again: twice), Critical Studies in Television, Adaptation and SERIES – International Journal of Serial Narratives. His 2017 book, The Changing Spaces of Television Acting, was made available last month in slightly more affordable paperback form. He currently has a pile of complimentary copies on his desk, but you are not going to get one.

Footnotes

[1] See how busy I am? I have actually started using abbreviations. It’ll be contractions next. And then maybe emojicons…

[2] A corruption of ‘mossy well’; there used to be a natural spring, said to have possessed healing properties when a chapelful of nuns lived here in the twelfth century.

[3] It’s literally at the top of a hill.

How brilliant Richard! Love the way that you convey passion and fascination for all these great things! And I hope you got your marking done! 🙂

Thanks for a lovely end-of-the-week read!

All the best

Andrew

Many thanks, Andrew! The marking is now complete, and I have just started a much-needed week of annual leave. I hope all’s well!

Take care

Richard