I seem to be thinking about the past lately—my last post, in fact, dealt with reboots, restarts, and remakes—and this month has me traveling back there again, this time through a “rabbit hole” at the back of a diner or, more appropriately, through one in my phone and TV. (Am I preoccupied, or am I responding to a cultural preoccupation? This recent article from USA Today suggests that it’s the latter. The occasion is Hulu’s new miniseries, 11.22.63, the James Franco time-travel thriller adapted from Stephen King’s 2011 opus. Franco plays King’s hero, mild-mannered English teacher Jake Epping. Drawn into an unlikely “quantum-leap” of sorts by Al Templeton, the gruff owner of a local diner, Jake, miraculously, finds himself back in 1960 and out to save JFK from Lee Harvey Oswald and that fateful day in Dallas. For Al, JFK is the hub of contemporary history, the proverbial butterfly for a string of beneficial consequences. If Jake can stop his assassination, Al promises, he “make[s] the world a better place” (1.1).

As much as Jake’s present-day sensibilities and his unique foreknowledge give him a significant advantage in the past—he makes large sums of money by betting on sporting events where he already knows the outcome, and he concocts stories about his past to fool others through anachronistic references to M*A*S*H and The Godfather—his mission is complicated by the historical questions that continue to linger about what happened that day. Before he can kill Oswald, he needs proof, Dexter-like, that he acted alone. And, like so many other time-travelers, Jake finds himself struggling with the things that he can’t control, like his hotheaded partner Bill Turcotte, his girlfriend Sadie Dunhill’s unstable husband Johnny, or, worst of all, the past itself.

If there is a monster in this series, it is not Oswald, but time. (As Gilbert Cruz notes, in his review of the novel for, ironically, Time, “Nearly 40 years into his career, King has finally found his most relatable villain” [“Doomed to Repeat”].) Jake can go back as many times as he wants and “reset” the past to 1960, but changing it is something else altogether. “The past,” Al warns him, “doesn’t want to be changed” (1.1). And the more that he tries to change things, the more that it ferociously resists. Cars speed out of control or fail to start. Cockroaches attack. Chandeliers drop dangerously from the ceiling. People die. And when all else fails, the past even gives him a potent case of intestinal distress.

King admits in his Afterword that he “originally tried to [tell this story] way back in 1972,” but that he abandoned the project because, among other reasons, “the wound was still too fresh” (846). Other television shows have gone back since then, and prior to the miniseries, to examine the scar, supporting Al’s belief in the pivotal cultural/historical impact of JFK’s assassination. In response to a Rolling Stone story about the show and in light of these possible influences, poster Jeffrey Roedel doubted King’s originality, quipping, “[He] got this idea from Quantum Leap” (“Discussion on Rolling Stone“). Sam Beckett does leap into Oswald in a two-part episode at the start of Season Five, and, in many ways, he is burdened with the same questions about Oswald’s guilt and conspiracy theories. Since Sam’s leaps are based, specifically, on the premise of “putting right what once went wrong,” writer Donald P. Bellisario cleverly finds a way to make the past “give” for Sam, by sending him back to save Jackie, instead of JFK. (“Your Swiss cheese mind probably doesn’t remember,” Sam’s “Al” tells him, “but, the first time, Oswald killed Jackie, too” (5.2)) His success, thus, becomes the history that we take as a given, an alternate reality in the scheme of the show that we have unknowingly accepted.

(In an odd bit of intertextuality, Sam Beckett actually meets a young “Stevie King” in 1964 in Season Three’s “The Boogieman,” when he becomes second-rate horror writer Joshua Rey. As the episode comes to a close, Sam considers his accidental influence on the author and all of the material that he “just gave him” (3.5). On the level of television reality, then, Sam, a time-traveler, inspires King, who will go on to write a novel about a character who time-travels back to the sixties, which will, in turn, be adapted into a television miniseries. So, maybe King did get this idea from Quantum Leap.)

Mad Men brings us back to the moment of Kennedy’s death as well. King mentions the show in some supplementary material to the novel, but points out that, for Jake, the sixties are “jarring in a way that Mad Men isn’t” (852). Where Jake struggles to blend in, the characters on Mad Men are a part of that world and rightfully know it as their own. They experience Kennedy’s death for the first time in Season Three’s “The Grown-Ups” largely as media moments, with people in the Sterling Cooper offices or in the kitchen at Margaret Sterling’s wedding watching it all unfold on TV. While they don’t change that outcome, Don rewrites history somewhat in the finale, by becoming the ad man to dream up that Coke commercial.

In his book Time Travel: The Popular Philosophy of Narrative, David Wittenberg suggests that, “since even the most elementary narratives, whether fictional or nonfictional, set out to manipulate the order, duration, and significance of events in time [, …] one could arguably call narrative itself a ‘time machine’” (1). If we follow this line of thinking, inasmuch as they offer up a reconstructed version of the past, all television shows about it, whether they attempt to rewrite the past or present it as accurately as possible, are time-travel shows of a sort. Regardless of where they bring us—from a formal dinner at the Drapers to a more laid-back afternoon in Eric Forman’s basement—they bring us back to something that is at once familiar and foreign, to a time that is being recalled even as it is being reworked to serve a setting, a storyline, and/or a personal or political perception. (In terms of the politics behind this kind of time-traveling, I am reminded of what Ryan Lizardi says about television nostalgia, in his Remake Television essay and elsewhere, “as a neutering force that limits the potential for critical gazes” by creating the illusion of “an unchanging and stable past” (38-39).)

Shows about time-travel complicate this conversation by revealing the metanarrative threads of the medium, even as they indulge in and contribute to them. In his essay “Quantum Leap: The Postmodern Challenge of Television as History,” for example, Robert Hanke conceives of Sam Beckett as “a figure of the viewer him/herself, whose contemporary viewing practices include zapping through television channels with remote control units” (72). Sam leaps from story to story and circumstance to circumstance like we do; in many cases, we also jump, like Sam, in medias res and must find our way through programming/narratives already in progress as we watch them.

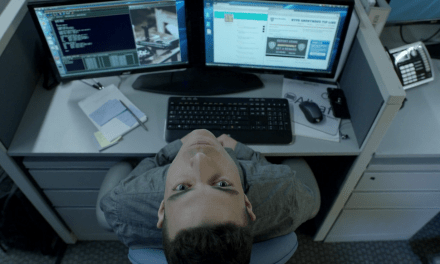

In this regard and whether intentional or not, 11.22.63, as a television production, also works as a metaphor about time and the medium itself. Now more than ever, we are all Jake Eppings of a sort when it comes to television, reworking time to suit our needs and increasingly traveling through it by an act of will and choice. The depth of programming allows us to enter a seemingly endless array of moments in television (and, perhaps, our own) history and to reset and re-experience them as they once were. We can watch Columbo solve a crime again and then see Diane Chambers get hired as a waitress at Cheers for the first time. Like Jake, we can stay there for a while and, on some level, immerse ourselves in what was. And, like Jake, our experience of time travel from the past to the present is unique in its duration. When Jake returns from his trips, only two minutes have passed in the present. Where we used to wait whole weeks for the networks to dole out their episodes, we can now compress that time into a day or two. Although Hulu only made one episode available each week, I binge-watched the miniseries on my phone toward the end of its run in a weekend. In some cases, I even went back through the rabbit hole and reset an episode to reacquaint myself with the trail of the narrative.

Changing the past on television, of course, is a different story. “The past is obdurate,” as King repeatedly reminds us in his book. They have yet to make a television that will rewrite what has been and keep Fonzie from jumping that shark or the screen from going black at the end of that Sopranos finale. We can reset it and go back, but we are bound by the rules of what must be, at least as far as the episodes themselves go. (When fan fiction and fan videos fail, we’ve still got our imaginations, and that service runs 24/7.) As I mentioned in my post on reruns, there is some comfort in the predictability of that constraint, and that may well have something to do with our watching.

But our most important trips back are ultimately driven by our humanity, by how key moments in those various television narratives made us feel, both good and bad, and how they still do. Although Al warns Jake against forming personal attachments, he is quick to break that directive, and both the novel and the series find their footing not so much through Oswald, JFK, and the larger historical consequences that loom in the background, but through the “smaller,” more personal ones that define him and have meaning for him, just as they define and have meaning for Sam Beckett—Jake’s need to change a childhood trauma for a custodian at his school in the present and his relationship with the small-town librarian who provides him with the love that he was lacking in 2016 as well. (“That’s why I came back,” he tells her, surprisingly (1.8).) Both the novel and the miniseries put these larger and smaller stories into conflict, forcing Jake to choose between what he wants and the greater good.

Perhaps, the real heroism that comes out of it all, as well as our own encounters with the past on television or elsewhere, isn’t in the courage to make “History” (with a capital “H”), but in the ability to accept the past and all that it means to us.

Douglas L. Howard is Chair of the English Department on the Ammerman Campus at Suffolk County Community College.