Teletubbies: Title

The British pre-school children’s television programme Teletubbies was made by Ragdoll Productions for BBC and first screened from 1997-2001. To my delight it was announced at the end of September that the series will return later this year, now produced by DHX Media. Ragdoll is an independent production company, and the commission for what became Teletubbies was for 260 twenty-five minute programmes, costing about £8.5 million. As a live action series with a relatively large budget and continuing investment, Teletubbies had an important role in defence of the BBC’s commitment to high-quality children’s programming. Children’s television is part of BBC’s public service mission, and today the same debates continue that were spurred by the economic success of Teletubbiesmerchandising and overseas sales (to 120 territories) a decade ago. On one hand, BBC demonstrated its continuing presence as a provider of free-to-air programmes for the public good, but on the other hand BBC was playing the same game as the commercial competitors whose brand exploitation and toy spin-offs seemed so foreign to the BBC’s remit.

Anyhow, it’s great television. The reflexivity and intertexuality of Teletubbies are its most notable features. The programme is set in what its creator Andrew Davenport called “the land where television comes from” (in the 1998 BBC documentary Big Hug: The Story of the Teletubbies), and there are numerous references to broadcasting, communication and storytelling. The Teletubbies greet their audience at the beginning of each programme, wave goodbye at the end, and the text hollows out a space for its audience to interact, for example by joining in the dances and songs that each programme includes. A giant windmill beams documentary segments of children in the “real world” beyond Tellytubbyland onto the Teletubbies’ bellies for them and the audience to see, aligning the Teletubbies and the audience with each other as spectators.

The Teletubbies receive television (rather than make it) and their agency is constrained by a giant windmill, the programme’s adult narrators and the instructions of Voice Trumpets that emerge from the ground, for instance. But the Teletubbies’ requests for the documentary sequences, dances and games to be repeated, and their refusal to disappear at bedtime, suggest both their own partial autonomy and their and the audience’s freedom to appropriate programme content, and the television medium itself, for their own pleasure. Television becomes a valued gift and an opportunity for joining in, thus familiarising television and its pleasures for the individual viewer and for an audience community.

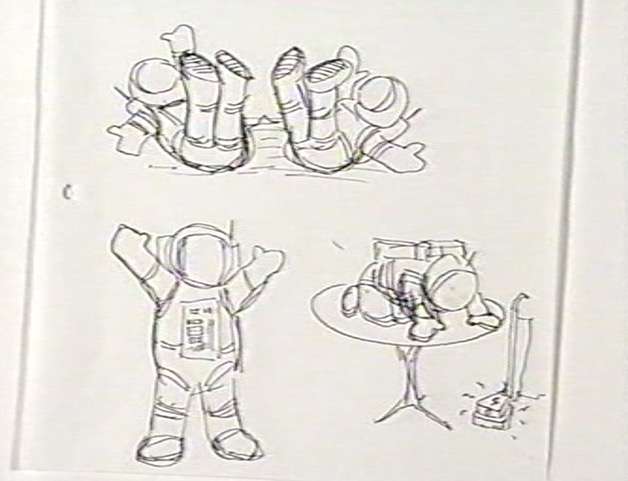

Teletubby spacemen

Andrew Davenport (working with Anne Wood, head of Ragdoll) imagined the Teletubbies through an analogy between toddlers and astronauts, and the image above is an original concept drawing by him, shown in the Big Hug documentary. The Teletubbies have human toddlers’ relatively large heads, short limbs and pear-shaped torsos, but also the clumsiness of astronauts in space-suits, falling over and losing dexterity in low gravity. Teletubbies are both like children and also like adults reduced to childlikeness by an alien environment. As if it were an alien place, like astronauts the Teletubbies explore what seems like a pastoral and familiar landscape. Clearly this furthers the programme’s child-centredness, and makes the Teletubbies analogous to children discovering the world around them. It also draws the adult and technological enterprise of space exploration into an analogy with children’s physical, sensory and cognitive underdevelopment; a “small step for Man” is like the small and tentative steps of a toddler.

Teletubbyland

But the Teletubbies are also in some ways uncannily monstrous and inhuman. The programme draws on science fiction’s popular forms for imagining aliens, by representing them as coloured, naked alien colonists who have aerials on their heads and understand Earth from the television pictures they have intercepted (as in the film comedy Earth Girls Are Easy). Teletubbies also provides opportunities for visual revelation of alien and intriguing creatures, objects and landscapes. Teletubbyland contains not only the rabbits, flowers and grassy sward of an idealised England, but also the Tubbytronic Superdome where the Teletubbies live with Noo-Noo the robotic cleaning machine.

Voice Trumpets emerge from among the flowers like giant air-raid warning sirens or periscopes. Animations in the programme draw on traditional narratives but foreground post-produced digital effects and digital morphing created virtually in a computer. This is another aspect of the dialectic between the alien and familiar. The interplay of traditional content with new production technology, along with the assumption that children will watch Teletubbies with other children or with parents, tames much of the potential for Teletubbyland’s uncanniness. The frequent repetition of fantastical sights and events, and the effect of music and voice-over to reassure, make Telebubbies a programme where strange things happen but where those strange things are enfolded within safe and familiar codes.

Some commentators have praised the relative lack of paternalistic instructional discourse in Teletubbies, since it celebrates children’s love of falling over, hugging and splashing in puddles. Other writers bemoaned its apparent lack of education in literacy and numeracy. These are old arguments about the aims, legitimacy and value of children’s television in an era of waning certainty about public service broadcasting. The issue is whether television, made by adults for children, should discipline and train the child on a journey towards adulthood, or whether television should cradle an Edenic and natural childhood, protecting it from adult culture.

My view is that Teletubbies thematizes this question (which is more interesting than answering it) by embedding television into the lived experience of the Teletubbies themselves and also of their audience. Rather than being something either good or bad that is outside of childhood, television for Telebubbies is already there within it. Television is represented as both familiar and alien, and so are the different worlds that it bodies forth. With remarkable charm and sophistication, Teletubbies invites its viewers into the pleasures of watching and interacting, not only with television but also with the possible and impossible worlds that it can conjure.

Jonathan Bignell is Professor of Television and Film at the University of Reading. He mainly works on the history of television drama for adults, but has also written about children’s television and toys. He is a Trustee of the Graduate Centre for International Research in Childhood (CIRCL) based at the University of Reading. A much longer and more theoretically developed version of ideas in this post was published as ‘Familiar aliens: Teletubbies and postmodern childhood’, in Screen vol. 46 no.3 (2005), pp. 373-388.