Putting aside watching or re-watching TV shows via box sets, the shows I watch as they are broadcast fall into two tiers. The first is made up of series that are, to use a cliché, appointment to view. At a set time each week the tea is made, computer turned off, answerphone turned on. Much of the nation rediscovered this joy recently watching Broadchurch, as did I, but to this I would add Dexter, The Walking Dead, American Horror Story, and Game of Thrones.

Then there’s the second tier. These are shows that I watch every week, that I won’t miss, but that I don’t mind recording and watching later, maybe the next day or the day after. At the moment this includes Doctor Who and Elementary. The interesting thing about Doctor Who is that in the past two years it has slid from being a first to a second tier show. I would never have thought of not watching Matt Smith’s first and, in particular, his second season live. This was the series for which the Radio Times referred to Steven Moffat as “cryptographer in chief”, involving a dazzlingly complex arc in which the final episode aired first, and which I watched live because I couldn’t wait to get the next piece of the puzzle, decipher the next clue, and avoid spoilers. But the producers have rolled back on complexity since then; the past two years being predominantly stand-alone episodes with a loose mystery lurking in the background. Despite oblique references to the ongoing “who is Clara?” story, you could comfortably watch the recent Hide or The Crimson Horror out of context, or indeed out of order, and still enjoy them.

The same is true for Elementary, the CBS produced Sherlock Holmes update currently showing in the UK on Sky Living. Elementary stars Jonny Lee Miller (with whom I went to school and appeared in a play, The Ragged Child, in 1984) as Holmes, now living in contemporary New York with Lucy Liu as Joan Watson, a sober companion assigned to help him through his recovery from drug addiction. The show is produced by Robert Doherty and Carl Beverley. Season one has three ongoing narrative arcs. The first involves Watson’s shift from sober companion to partner-in-detection; the second revolves around Irene Adler, the love of Holmes’ life whose murder drove him to his self-destructive path, and the third is the emergence of the figure of Moriarty, as ever a master criminal pulling strings behind the scenes. But these rest very much in the background, and have only really come to the fore as the season finale approaches. For the most part Elementary is precisely what Keith Johnston said in his last cst blog, a “formulaic police procedural.” It’s a show you can dip into and out of.

It’s impossible not to compare Elementary to Sherlock and equally to avoid the fact that Elementarysuffers in comparison. Whereas Sherlock is intelligent, Elementary is merely clever. In keeping the London base and reworking Conan Doyle’s original stories (“A Study in Pink”, “A Scandal in Belgravia”) Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss have crafted both a modernization and a witty homage, filled with loving touches such as Mrs Hudson’s (Una Stubbs) constant reminders that she’s a landlady, not a housekeeper, or having Holmes wearing nicotine patches rather than puffing on a pipe, or the fact that Holmes and Watson never take the tube but only take taxis, London’s contemporary Hansom Cabs. Beyond the device of making Watson a woman and developing Holmes’ cocaine habit into fully-fledged drug addition, Elementary lacks these kind of deft touches. Whereas London is an integral part of the drama in Sherlock, a landscape seen through windows, in reflections and in maps, New York in Elementary is merely background, rarely glimpsed in favour of a series of interior sets – Holmes’ brownstone, the police precinct, the crime scene and so on.

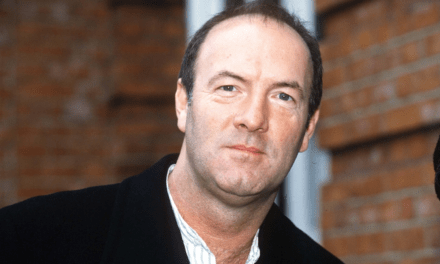

But while Elementary may suffer in comparison to Sherlock, nevertheless it is a highly entertaining hour of television. Formulaic it may be, but for me the formula works. While Miller may avoid the quirky intensity that Benedict Cumberbatch brings to the role of Holmes, Miller’s version is far more suited to the long haul of 24 episodes. He’s more confident than arrogant which makes room for hubris, and lacks thoughtfulness rather than empathy in his dealings with others, making him easier to connect with. Furthermore he is more emotional and therefore more vulnerable, his dismissal of the challenge of recovery occasionally giving way to show the real nature of his struggle, for example when he refuses his one-year sobriety chip because he relapsed (“Dead Man’s Switch” 1:20). His Holmes is bristling with nervous energy, waiving his arms around and rubbing his face in frustration, clearly seen in his introduction.

When Watson first arrives at Holmes’ house and introduces herself, Miller is bare-chested, still, staring intensely at her before bizarrely declaring his love. Once this is revealed to be him remembering and reciting lines from one of the many TV screens he is simultaneously watching, for the remainder of the sequence he moves quickly and relentlessly, dropping bits of information while getting dressed and heading out. It’s very different to Holmes’ first meeting with Watson in Sherlock which emphasises his deductive powers and where he comes across much more coldly.

Miller’s is not a Holmes of quiet contemplation but of restless motion. Where Cumberbatch’s Holmes is crafty and manipulative when interrogating a suspect for information, Miller’s is blunt. Although it is often implied that he sits and thinks for hours, this is never seen. We always come in at the moment he is ready to act. In a sense this fits the model of the police procedural. By the time the murder is set up and time taken out for adverts, there’s only around 35-40 minutes left to actually solve the crime, so no time to dally.

Sherlock may well ooze class, but there’s something satisfying about Elementary’s combination of weekly crime solving with the slow burn of the arc narratives and the excellent central performances. Formulaic it may be, but it’s a fresh take on an old formula, in comparison to something like Boneswhich has moved beyond formula into the realms of routine. I guess the point I wish to make is this. The television series that are grabbing people’s attention are becoming increasingly specialised. They are mostly shows with shorter seasons in the HBO mould, 12 or 13 episodes, and often push boundaries of sex, violence and language. All my tier one shows above fall into this category. But I never want to lose my love of the comfort that really good, well-made, formulaic TV can bring. And there’s nothing elementary about Miller and Liu’s performances.

Simon Brown is Director of Studies for Film and TV at Kingston University. His main research areas are early cinema, British cinema and contemporary American television, and he has published pieces on shows as diverse as Dexter, Alias, Supernatural and The X-Files.