Good true crime is like an onion: each layer, each episode, revealing more of the complexity of the case, more about the character and behavior of the suspects, more about possible motives and alibis, and more potentially compromising truths.

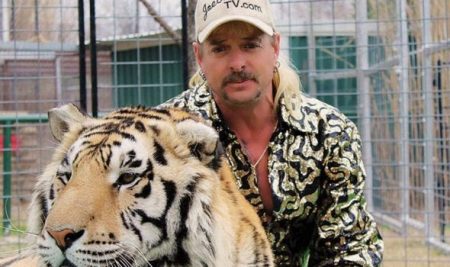

In Netflix’s Tiger King (2020), each layer reveals more, well … crazy. It’s the story of private zookeeper and self-described “gay, gun-toting cowboy with a mullet” Joe Exotic (Joseph Maldonado-Passage), who in 2019 was convicted on multiple counts of animal abuse and two counts of murder-for-hire and sentenced to 22 years in federal prison.

Released on March 20, at the dawn of the age of quarantine, Tiger King has been wildly successful.

According to Nielsen’s SVOD (subscription video on-demand) content ratings, the series reached 34.3 million unique (U.S.) viewers in its first 10 days of release, topping Season 2 of the streamer’s hit series Stranger Things. Within days of its release, Tiger King had become the most popular title on Netflix and was rated as the most popular show on television by review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes scoring 97% approval with critics and 96% with audiences.

And it’s easy to see why the show has become such a phenomenon: Its protagonist is a charismatic, befringed force of nature – a big cat keeper and breeder, travelling showman, TV host, country music singer*, and aspiring politician who leans into his eccentricities and has a pro wrestler’s instinct for what makes for good television theatrics.

The world he inhabits is equally bizarre, and the docuseries’ plot (such as it is) fairly bristles with dangerous animals, conspiracies, betrayals, exploitation, romance, gunplay, shirtless interviews, redneck zaniness, soap opera rivalries, New Age guru-ism, polygamy, a mysterious disappearance, lawsuits, a pair of attempted contract killings, fraud, more exploitation, an Oklahoma gubernatorial campaign, a possible sex cult – and all of it wrapped in acres of tiger print and gold lamé.

As one meme has it, the show has everything. It’s a perfect storm of outrageousness conveniently timed for our new stay-at-home-and-binge-watch-television reality.

But while the series is billed as true crime (its subtitle is “Murder, Mayhem, and Madness”), the designation doesn’t quite fit. Sure, there’s the murder-for-hire scheme – the result of a bitter and very public feud between Maldonado-Passage and Florida animal sanctuary founder Carole Baskin – and the insinuation, if not outright documentation of animal welfare violations.

But in the grand scheme of the series these points tend to get lost, subsumed by the reality TV-style emphasis on its characters’ larger-than-life personalities, their melodramatic antagonisms, and strangely addictive wackiness.

It’s a train wreck, as others have observed, a manic spectacle that allows us, for at least a few hours, to forget about the submicroscopic threat that is devastating our lives.

We are fascinated by the stranger-than-fiction-ness of it; we watch dumbfounded as the craziness just seems to get crazier; we revel (or we seem to be encouraged to) in the schadenfreude that typically attends representations of redneck aesthetics and behavior in mainstream culture – and of which I am becoming increasingly impatient. (Indeed, one wonders how that shirtless interview with John Finlay came to happen – it seems a bit too on the nose).

And perhaps the series’ singular absurdities remind us of the world we lost, and that may yet return: a world of undervalued liberties and social togetherness in which we might have unexpectedly encountered colorful characters, new experiences, and new subcultural scenes – a world that now seems so innocent, and so far away.

It struck me, however, that in a series that seemed to place moral concern on the unregulated practices of private zookeeping, there was not one interview with a representative from a major public zoo, a zoologist, or veterinarian. This seems a major oversight – particularly as filmmakers Eric Goode and Rebecca Chaiklin have evidently claimed that they intended the series to be a Blackfish for big cats. I wanted the input from an expert, someone who could outline the difference between private zoos and public ones, and who could explain the ethical issues involved in breeding and trading exotic and endangered animals.

This is not to say that I doubt the argument that the practices of Joe Exotic and his associates aren’t manifestly atrocious. They are. But I needed more of a counter-point than what was provided in the series by Carole Baskin – herself a “main character” in the drama, and so not the best choice for an objective viewpoint – and the several animal rights advocates that were briefly interviewed in the series’ final episodes.

(Indeed, it is suggested by the documentary that Baskin’s treatment of animals – and her human volunteers for that matter – shares certain features with the practices of Joe Exotic and the other private zookeepers whose operations she decries. Yet her Big Cat Rescue is an accredited animal sanctuary; so the viewer is left wondering if there are legitimate criticisms of her operation, and, more cynically, whether she might just be an independent zookeeper with a professional staff, the perspicacity to cultivate an activist image, and the wherewithal to obtain the appropriate credentials).

Instead, everyone featured in the series, on either side of the debate, was a passionate participant. And though there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with having passion for one’s convictions, the way in which it was presented by the filmmakers had the feel of a battle royal (again, I use the wrestling term), rather than that of a documentary that was dedicated to making a compelling moral argument.

What the series did show me, other than a community which I did not know existed, was the way in which narcissistic personalities can be compelling, can attract a following, and inspire loyalty – indeed, how monumental egos, in the age of digital media production and image management, can create their own realities.

There are obvious parallels to contemporary politics here. And I’m struck by the way in which some such egoists – like Joe Exotic – eventually implode, while others become too big to fail.

Andrew J. Salvati is an adjunct faculty member at Drew University. He earned his Ph.D. in Media Studies at the Rutgers-New Brunswick School of Communication and Information in May 2019. His research centers on the ways in which American history has been presented in popular media, including television, film, podcasts, mash-ups, and computer games. His dissertation, “Small Screen Histories: Presenting the Past on American Television, 1949-2017” examines the ways in which the producers of historical documentaries and docudramas construct “usable pasts” that speak as much to the concerns of the present as they do to the past. His work has also appeared in the journals Rethinking History and the Journal of Radio and Audio Media.