We are in more than an evolution. We are in a revolution of communication and cinema or movies or whatever you want to call it.

— Martin Scorsese, 19 December 2019 (Galloway 106)

Martin Scorsese first moved to Hollywood in 1971. He was an outsider then, regularly hanging out with other young aspiring directors of the so-called film generation, especially the slightly older Francis Coppola and Brian DePalma, along with his immediate peers, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and John Milius (Pye and Myles). They all achieved insider status in the industry over the next decade. Together they transformed Hollywood by occasionally collaborating, but always actively advising and supporting each other and their latest movies. They were all talented and shared a love for theatrical films that bordered on an obsession.

When Scorsese made the above observation at The Hollywood Reporter’s annual awards-season directors’ roundtable, he was the éminence grise of the group at 77, which also included Greta Gerwig (36) for Little Women; Lulu Wang (36) for The Farewell; Todd Phillips (48) for Joker; Noah Baumbach (50) for Marriage Story; and Fernando Meirelles (64) for The Two Popes. Notably, half the filmmakers represented (Baumbach, Meirelles, and Scorsese for The Irishman) had produced and directed their movies for Netflix.

Even more importantly, Scorsese made this prescient remark without he or anyone else in the film community having the faintest idea that they would be experiencing a worldwide coronavirus pandemic in less than three months. Hollywood had weathered other wholesale and unforeseen disruptions before, be they technological or economic, grand social upheavals or even world wars. Still, only once before had the movie industry ever encountered a global health emergency of this magnitude.

Vid. 1: ‘1918 Flu Pandemic’ from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on 5 June 2018 (1:32)

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic—erroneously referred to at the time as the Spanish flu—lasted approximately 15 months from early spring of 1918 until the summer of 1919. It infected 500 million people or about one-third of the earth’s population. It killed an estimated 50 million individuals worldwide including around 675,000 Americans (Barry). As a comparison, World War I—known as the Great War—resulted in a total of 45 million casualties comprised of 22 million deaths and 23 million wounded.

Despite the 1918-19 flu’s shocking number of fatalities, it was ‘America’s forgotten pandemic,’ according to one eminent historian who wrote one of the most important and influential books on the subject (Crosby). Film scholar, Richard Koszarski, similarly argued that ‘while the war would long be celebrated in song and story, and immediately recognized as a defining event in twentieth-century history, the flu was almost too terrible to remember’ (466). Nevertheless, the 1918 Influenza Pandemic had a profound and transformative effect on the fledgling motion picture industry in that it hastened the emergence of the classical Hollywood studio system, which continued its international expansion and maturation for three more decades through the end of World War II.

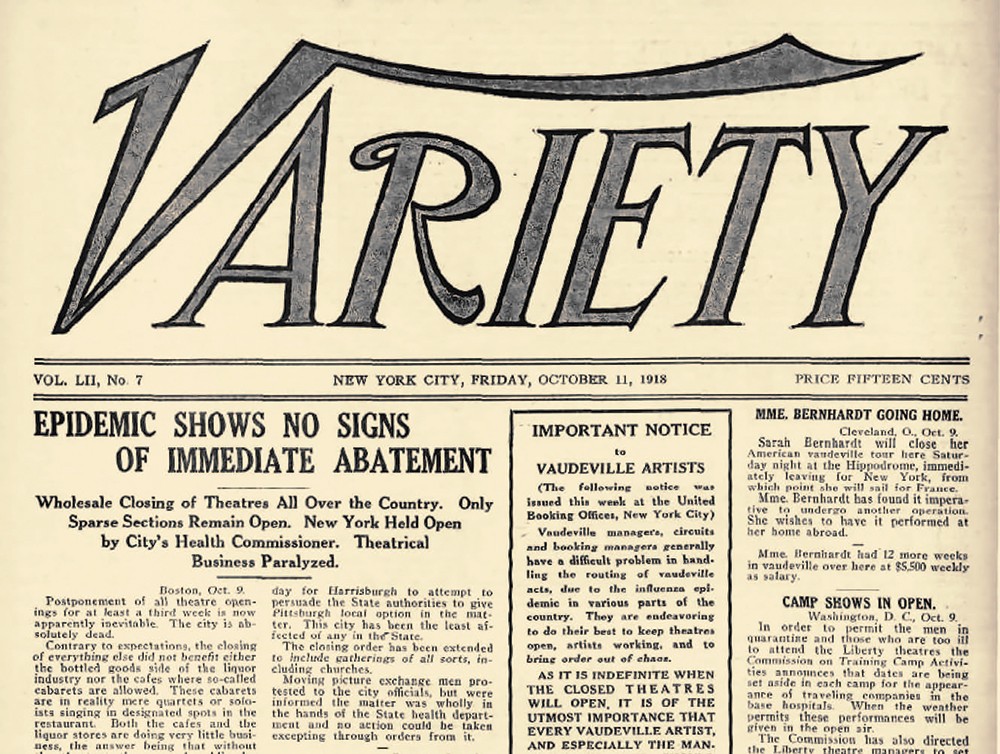

The 1918-19 flu epidemic shook the foundations of the fledgling film business. Koszarski reported that ‘Photoplay estimated that 80 percent of the movie houses in the United States and Canada had closed for between one and eight weeks, losing $40,000,000 in revenue and putting 150,000 employees temporarily out of work’ (468). For example, Paramount, the distribution arm of Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players-Lasky, lost an estimated $2 million (roughly equivalent to $30 million today). The exhibition sector of the industry was hit even harder as the mostly independent mom-and-pop movie houses began closing at an alarming rate.

Fig. 1: Lead Story in the 11 October 1918 issue of Variety: ‘Wholesale Closing of Theatres All Over the Country’

Adolph Zukor approached this calamity as an opportunity. He gambled much of his remaining capital to relentlessly and ruthlessly acquire as many financially strapped theatres as possible as his way of guaranteeing a market for Famous Players-Lasky films. Paramount thus procured around 135 movie houses in 1919 alone, thus pioneering vertical integration (production-distribution-exhibition under one corporate umbrella) in Hollywood. Over the next decade, the Publix Theatres branch of Paramount grew to nearly 2,000 screens. Eventually MGM, 20th Century Fox, RKO, and Warner Bros. followed a similar acquisition policy.

Of course, other technical, industrial, and aesthetic innovations marked the coming golden age of American movies, but none was more significant and signature to the new Hollywood model than vertical integration. Odds are that this degree of corporate consolidation would have happened anyway, but the disruption caused by the influenza pandemic definitely accelerated this change. By the early-to-mid 1920s, Zukor was as powerful as any mogul in the film industry, and the top-down Hollywood system that he and his partners had facilitated bore little resemblance to the decentralized U.S. movie business that existed before 1918.

Fig. 2: (Left to right is the executive team heading up the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation circa 1916) Jesse L. Lasky, Adolph Zukor, Samuel Goldwyn, Cecile B. DeMille, and Al Kaufman

Likewise, the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic is proving to be a moment of truth for the contemporary movie sector of the entertainment industry. According to U.S. Department of Labor statistics through April, ‘arts and entertainment’ employment has already plummeted 54.5%, which is more than ‘food services and drinking places’ down 48.1%; ‘performing arts and spectator sports’ down 45.4%; and ‘accommodation’ (lodging) down 42.3% (Paine). As of May 20th, ‘890,000 film and entertainment employees’ have been laid off so far in Hollywood this winter and spring (Gardner).

Theatrical exhibition in particular is in dire straits. In the Asia-Pacific market where the pandemic began, total movie ticket sales fell 88% in the first-quarter (January-March) of 2020 (‘Big Number’). In North America, the crash happened three months later. Revenue figures from IMDB’s Box-Office Mojo reports that for the last week (March 6-12) before movie houses began shutting down, the overall take was $134,543,546 across 100 theatrical releases. A month later (April 3-9), the total gross was an anemic $5,925 with only two new releases.

In response, Wall Street analysts began downgrading domestic movie theatre chain stocks in early April and predicting eventual Chapter 11 bankruptcy filings later in the summer (Szalai). To put this development into perspective, the National Association of Theatre Owners (NATO) lists that there are currently 41,172 screens whereby five major chains exceed the 1,000-screen benchmark (AMC 8,043; Regal 7,178; Cinemark 4,630; Cineplex 1,695; and Marcus 1,106).

Movie theatres will no doubt survive the pandemic. Chapter 11 probably signals restructuring in most cases rather than going out of business. There may be some corporate takeovers, however. Plus the theatrical movie market and the number of screens will likely shrink—maybe dramatically. At the moment, there are 200 movie theatre locations in North America screening films; 150 of them are open-air drive-ins. More tellingly, Performance Research conducted a nationwide survey in mid-May and a whopping 70% of respondents revealed that they would currently rather watch a movie at home than in a theatre; 13% still preferred a local cinema; and 17% were not sure (Vary).

Some studios have quickly shifted gears by making a few select features available directly to consumers through streaming at $19.99 for a 48-hour rental, such as Universal with The Invisible Man on March 20 (after a brief theatrical run starting on February 28); The Hunt also on March 20; and Trolls World Tour on April 10. Most distributors though either pushed back the original debut dates of their movies until later in 2020, such as the latest United Artists/Universal James Bond-release, No Time to Die, from April 10 to November 25; or opted for a 2021 date to-be-determined such as Disney’s Jungle Cruise with Dwayne Johnson and Emily Blunt.

Theatricality is the buzzword that film industry insiders use to describe a movie that they believe needs to be seen on a big screen. Warner Bros. executives are expressing high hopes for the summer box-office potential of Christopher Nolan’s $205 million-budgeted sci-fi-spy-thriller, Tenet, still scheduled to open on July 17. For his part, Nolan has been confidently advocating that his high-concept theatrically-designed blockbuster is just the film to reboot movie theatres back into business. Whether worldwide moviegoers in the tens of millions will agree remains to be seen.

Vid. 2: Trailer from Warner Bros. Pictures for Christopher Nolan’s Tenet (2:50)

What is more certain is that screen entertainment is in the middle of a revolution—as Martin Scorsese so astutely pointed out—and the current coronavirus pandemic will catalyze and expedite whatever changes are already underway in ‘communication and cinema.’ Given the enormous investment made by Warner Bros., studio decision makers may ultimately push back the release of Tenet to later in 2020 or 2021 as their wisest course of action. Even so, Hollywood is desperate to reopen and there are indications that it is beginning to occur, but theatrical exhibition is the one sector where the options remain a choice between bad or worse.

Stunning unemployment rates, impending business failures, and defensive 20th century-styled tactics once again characterize the strategies of most large and small movie chains. For instance, AMC Theatres CEO, Adam Aron, threatened to boycott all Universal films in the future when the studio recently released The Invisible Man, The Hunt, and Trolls World Tour on-demand. No chain is built to withstand a pandemic. Even when instituting best practices, no movie house is constructed to be profitable at one-half to one-third capacity. In addition, fewer customers will buy concessions, which is where theatre owners reap their largest revenues.

Even taking all those factors into consideration, theatrical movies now have an increasingly popular technological replacement—streaming. Netflix CEO, Reed Hastings, and his chief content officer, Ted Sarandos, are the Adolph Zukor and Jesse Lasky of the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic. Netflix is the current undisputed leader in the online media services sector of the entertainment industry with 182 million subscribers worldwide (of which 69 million are in the U.S.) as of 1 April 2020. So far Hastings has been shrewdly noncommittal about acquiring properties in the depressed theatrical movie sector.

Netflix’s growth was actually flat in North America, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa in 2019. Forecasts for the streaming giant were tepid going into 2020 given its growing number of competitors in an ever-crowded sector. Still, Netflix doubled expectations by signing up 15.77 million new subscribers during the first-quarter of this year as one of the unexpected consequences of the coronavirus pandemic. Ted Sarandos also published a May 4 Op-Ed piece in the Los Angeles Times signaling to both Netflix’s Hollywood and Silicon Valley competitors as well as the industry’s creative talent that it has already restarted its production activities in Korea, Japan, and Iceland with more countries soon to follow.

In the short term, the recent shelter-in-place phase of the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic has benefited all the major players in the ongoing streaming war, but no online provider more so than Netflix, which is completely focused on entertaining people in their homes. Nevertheless, Amazon Prime Video has similarly grown to 150 million global subscribers; and the newly launched Disney+ and Apple TV+ (in November 2019) are today up to 54.5 million and 33.6 million paying customers, respectively.

Suffice it to say, the future belongs to streaming. What the coronavirus pandemic is doing is fast-tracking subscriber adoption rates for these online media services and, in turn, irrevocably revolutionizing how the majority of people worldwide watch movies.

As a final note, The Guardian’s film editor, Catherine Shoard, recently solicited and curated two-dozen remembrances from filmmakers and critics on the ‘communal thrill of going to the movies’. It is a delightful compilation that film lovers of all ages can enjoy with such relatable observations as Ken Loach recalling how La Ronde (1950) ‘was an escape to an exotic world far removed from the industrial Midlands’; Steve McQueen affirming how he ‘had butterflies in my stomach right up to my chest’ upon seeing The Magnificent Seven (1960) at the Hammersmith Odeon; and Sarah Polley captured ‘a glimpse of what faith meant,’ while viewing The Thin Red Line (1998) in Toronto, where ‘in the dark of the cinema, among strangers, I was transformed.’

Fig. 4: ‘That childhood excitement has stayed with me’: Salvatore Di Vita (Salvatore Cascio) in Cinema Paradiso (1988)

These and twenty-one other ‘memorable moments at the movies’ are accompanied by the familiar image of young Salvatore’s wondrous gaze as he is transfixed and transported outside himself as he watches a movie in writer-director, Guiseppe Tomatore’s semi-autobiographical Academy-Award-winning Cinema Paradiso (1988). The effect of the assembled collection is joyous yet bittersweet. It is a shared commemoration of the theatrical filmgoing experience if also an unspoken elegy to a much loved analog tradition from the 20th century that is now slowly giving way to an increasingly popular array of digitized viewing practices in the 2020s.

Cinema Paradiso is a fable about celebrating the past while also moving on. In the first act of the film, the old movie house burns to the ground in an unfortunate and unforeseen accident that leaves the house projectionist, Alfredo, permanently blinded when a nitrate reel explodes in his face. The child, Salvatore, is the only other person in their small town of Giancaldo who knows how to run the machine since Alfredo befriended him earlier and taught him how to use the projector.

The townsfolk eventually rebuild a Nuovo Cinema Paradiso and young Salvatore becomes Alfredo’s surrogate as the new projectionist. They grow ever closer but Alfredo finally is forced to tell the now older teenaged Salvatore that he must leave their small village and follow his ambition of becoming a filmmaker.

Alfredo: Get out of here! Go back to Rome. You’re young and the world is yours. I’m old. I don’t want to hear you talk anymore. I want to hear others talking about you. Don’t come back. Don’t think about us. Don’t look back. Don’t write. Don’t give in to nostalgia. Forget us all. If you do and you come back, don’t come see me. I won’t let you in the house. Understand?

Salvatore: Thank you. For everything you’ve done for me.

Alfredo: Whatever you end up doing, love it. The way you loved the projection booth when you were a little squirt.

Not ‘giving into nostalgia’ is especially sound advice in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. The old ways of watching motion picture art and entertainment are to be loved while they last, but so too are the newer modes of screen storytelling and the corresponding practices that are emerging to experience them. Film in 2020 is a legacy term and loving it in all of its many manifestations is not an either/or proposition. The future of movies promises to be as exciting as its past.

Gary R. Edgerton is Professor of Creative Media and Entertainment at Butler University. He has published twelve books and more than eighty-five essays on a variety of television, film and culture topics in a wide assortment of books, scholarly journals, and encyclopedias. He also coedits the Journal of Popular Film and Television.

Works Cited

Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. Revised Edition. New York: Penguin, 2005.

‘Big Number: $528M,’ Hollywood Reporter. 6 May 2020: 13.

Crosby, Alfred W. America’s Forgotten Pandemic. 2nd Edition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Galloway, Stephen. ‘“A Revolution of Cinema”: Director Roundtable,’ Hollywood Reporter. 19 December 2019: 104-111.

Gardner, Chris. ‘Entertainment Industry Has Lost “Many” of its 890,000 Jobs During COVID-19 Pandemic, L.A. Official Says,’ Hollywood Reporter. 20 May 2020 at https://hollywoodreporter.com/news/entertainment-industry-has-lost-890000-jobs-covid-19-pandemic-la-official-says-1295373.

Koszarski, Richard. ‘“Moving Picture World” Reports on Pandemic Influenza, 1918-19.’ Film History, 17.4 (Winter 2005): 466-485.

Paine, Neil. ‘The Industries Hit Hardest by the Unemployment Crisis,’ FiveThirtyEight. 15 May 2020 at https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-industries-hit-hardest-by-the-unemployment-crisis/.

Pye, Michael, and Lynda Myles. The Movie Brats: How the Film Generation Took Over Hollywood. Revised Edition. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1979.

Sarandos, Ted. ‘Op-Ed: How Film and Television production can safely resume in a COVID-19 world,’ Los Angeles Times. 4 May 2020 at https://latimes.com/opinion/story/2020-05-04/film-and-television-production-can-resume-in-a-covid-19-world.

Shoard, Catherine. ‘“I barely breathed”: Tilda Swinton, Emma Thompson, Steve McQueen and more on their most memorable moments at the movies,’ The Guardian. 15 May 2020 at https://theguardian.com/film/2020/may/15/barely-breathed-tilda-swinton-emma-thompson-best-ever-nights-at-movies.

Szalai, Georg. ‘AMC Theatres “Bankruptcy Appears Likely,” Analyst Says,’ Hollywood Reporter. 9 April 2020 at https://hollywoodreporter.com/news/amc-theatres-bankruptcy-appears-analyst-says-1289514.

Vary, Adam B. ‘Study Shows 70% of Consumers Would Rather Watch New Movies at Home (EXCLUSIVE),’ Variety. 20 May 2020 at https://variety.com/2020/film/news/new-movies-better-at-home-than-in-theaters-performance-research-1234611208/.