Canon: A collection or list of sacred books accepted as genuine: ‘the biblical canon’; The works of a particular author or artist that are recognized as genuine: ‘the Shakespeare canon’

(Oxford Dictionaries. Online)

Apologies, but I’ve marked an awful lot of student essays recently (and I do mean awful). This stylish trend for opening one’s work with an easily Googled dictionary definition is infectious.

In the worst possible sense.

See? I’ve even started using sentence fragments…

This will come as a surprise to those of you who think of me as a stuffy old British television historian, but today I am focusing on American television.

Old American television, but you shouldn’t expect miracles. However, I shall make my historical musings seem more contemporary than they actually are by cleverly framing them with reference to something that is happening now: in the present, as it were.

So, have you heard about this new Star Trek: Discovery (CBS, 2017), then? You can’t get much more current than that; it’s not even out yet. Set a decade before what we are now supposed to refer to as Star Trek: The Original Series (NBC, 1966-69) (or, to those in the know, the somewhat dismissive acronym TOS), this latest iteration of the sci-fi brand was first announced in November 2015, and should make its debut later this year.

Focusing on the voyages of the Starship Discovery (the Enterprise NCC-1701 is at this point being captained by Christopher Pike, who will later come a cropper with some delta rays after Kirk takes over), this will be the fifth television spin-off/iteration of the Star Trek universe since the 1960s crew boldly went. The other versions have been, as I probably need not tell you: Star Trek: The Next Generation (Paramount, 1987-94); Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (Paramount, 1993-99); Star Trek: Voyager (Paramount, 1995-2001); and the comparatively short-lived prequel Star Trek: Enterprise (UPN, 2001-2005).

That is to say, Star Trek: Discovery is the fifth official version.

But in fact – as a great man/goblin once said – there is another…

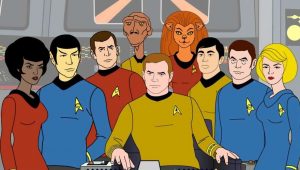

Star Trek: The Animated Series (or just plain Star Trek, according to the on-screen credit) was very much the missing link between the original adventures and the later film series. Produced by Filmation and distributed by Paramount Television, it was broadcast by NBC in the US between 1973 and 1974, and was shown here in Britain by the BBC in 1974 and 1976. I used to watch it after getting home from school, and to me it was every bit as exciting as the live action series. I mean, it was a cartoon! Executively produced by original Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry and series writer D.C. Fontana, the show seemingly had an authorial imprimatur that positioned it as keeper of the Star Trek flame, albeit in animated form as opposed to live action, and with much shorter episodes. For starters, the majority of the cast returned to voice their characters. At first the intention had been to employ only William Shatner (Captain Kirk, as if you needed telling), Leonard Nimoy (Mr Spock), DeForest Kelley (Doctor Leonard ‘Bones’ McCoy), James Doohan (Montgomery ‘Scotty’ Scott) and Majel Barrett (Nurse Chapel), but Nimoy, in an admirable act of solidarity, held out on signing his contract until George Takei (Sulu) and Nichelle Nichols (Uhura) were also hired. There wasn’t enough money in the pot to bring back Walter Koenig (Chekov), but he was given his first screenwriting credit on the show by way of compensation. Other returning Star Trek alumni included director-turned-writer Marc Daniels, and Tribble creator David Gerrold.

Boldly going. Again.

To all intents and purposes, Star Trek: The Animated Series’ two seasons comprised the fourth year of the original crew’s mission (to seek out new life, etc.), drawing heavily upon its predecessor’s mythology while simultaneously expanding the Trek universe. Several stories were effectively sequels to old episodes, and featured returning characters such as intergalactic rogue Harry Mudd (now peddling a love philtre which – surprise, surprise – gets Spock all hot under the collar over Nurse Chapel), Spock’s father Sarek, and Tribble trader Cyrano Jones, all voiced by their original actors. Klingons Kor, Koloth and Korax also made repeat appearances, albeit now voiced by the versatile James Doohan. Visually, clear links were made to the 1960s version, from the title sequence and lettering to the designs of regular characters, costumes and sets. While Alexander Courage’s original music was not re-used, the new theme, credited to Yvette Blais and Jeff Michael, was as close as dammit, and even featured the same ‘whoosh’ effect as the Enterprise sped past to fresh adventures.

Whoosh.

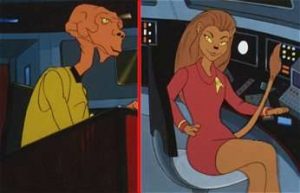

However, there were also innovations. With Chekov absent, a replacement helmsman was required, and – exploiting the possibilities of the animated format – the Russian was replaced by Edosian Lieutenant Arex, an angular, dog-like character with three arms and legs, who would have been impossible to realise on the original show’s budget (I am doubtless not the first to observe that the vast majority of alien life forms encountered in Trek are essentially humans with funny ears or ridged foreheads). Possibly less convincing – but infinitely more desirable – was the leonine M’Ress, a Caitian who took charge of communications whenever Uhura was off duty. Voiced by Majel Barrett, M’Ress had a habit of purring or growling softly at the end of each sentence that I find strangely arousing.

New arrivals Arex and M’Ress. Grrrrrrrrrrr…

Another addition was the recreation room, which bore more than a passing resemblance to the later holodeck of The Next Generation. However, arguably the biggest contribution made by The Animated Series was in terms of visual design. Whereas the standard of animation is basic by modern standards, this was the first time that the alien worlds and creatures encountered by the crew became truly fantastic, featuring a level of imagination that the live action versions – and arguably even the recent films – never quite managed to meet.

Fantastic!

Of course, it couldn’t all be good. The live action productions probably wouldn’t have bothered with the telepathic aliens in ‘The Eye of the Beholder’, even if they’d had the means:

Less fantastic…

In terms of contributing to the mythology, The Animated Series gave us an important insight into Spock’s youth in ‘Yesteryear’, an episode in which the Vulcan utilises a time portal (previously seen in ‘City on the Edge of Forever’) to put right a temporal slip-up whereby his younger self was killed during the kahs-wan maturity test. It is here that we first see the boy Spock being bullied by his peers due to his half-human lineage – a scene that was subsequently repeated for the big screen reboot (which is, technically, both a sequel and a prequel) in 2009.

The Animated Series also provided a minor but significant addition to Star Trek lore when it at last clarified what James T. Kirk’s middle initial stood for. In a continuity flaw that we need not engage with here, this was initially indicated as ‘R’ on a headstone in the second pilot episode ‘Where No Man Has Gone Before’, but had been ret-conned to the now-familiar ‘T’ by the end of the original run. However, it was only in The Animated Series that we learned this stood for Tiberius – a fact that has been adhered to ever since.

This may sound like heresy, but many Animated Series episodes are actually much better than the originals. Surely only a fool (or a masochist) would choose to watch ‘Spock’s Brain’ over ‘Yesteryear’? Although primarily conceived as Saturday morning children’s fare, the serious intent behind the animated version (backed up by contributions from such heavyweight sf writers as Hugo and Nebula winner Larry Niven) meant it kept faith with already-devoted fans, but did not alienate its target youth audience. The show even won a Daytime Emmy Award in 1975 for Best Children’s Series.

This is all impressive stuff, and I honestly recommend any Star Trek enthusiast who has not seen the programme (unlikely, but possible) to take a look; you will be pleasantly surprised. However, The Animated Series came and went all too quickly, and more than a decade later – by which time The Next Generation was up and running, if not yet quite the success story it would later become – executive producer Gene Roddenberry had a change of heart, declaring the cartoon series non-canon. Spock’s traumatic childhood on Vulcan (and the fact that Robert April, seen in ‘The Counter-Clock Incident’, was captain of the Enterprise before Pike) had already been established in a guide approved by franchise owners Paramount, but as far as Roddenberry was concerned, anything else in The Animated Series was no more valid than bog standard fan fiction – a position from which he never retreated.

In my view, this was more than a little harsh. OK, the life support belt and aqua shuttle may not have caught on, but The Animated Series clearly made some significant contributions to the on-going Trek narrative. It also broke with tradition – thus paving the way for The Next Generation – by allowing the supporting cast a far greater share of the action than had been the case in the 1960s, as when Uhura capably takes the helm of the Enterprise in ‘The Lorelei Signal’. Nevertheless, the show fails to feature in the majority of academic writing on Trek (and, let’s face it, there’s plenty of that). It doesn’t appear in Pearson and Messenger Davies’ excellent Star Trek and American Television – With a Foreword by Patrick Stewart (2014) – about which Roberta seemed unfazed when I attempted to upbraid her last year (even the unmade Star Trek: Phase II gets a couple of mentions).

The question of canonicity is of course a thorny one, and it is interesting to consider whether a man who liked to be known as The Great Bird of the Galaxy should really be allowed the final word on what ‘counts’ as Star Trek. Doesn’t each viewer have the right to make up their own mind regarding the validity of the textual universe? Now that Disney has taken over the Star Wars franchise, the formerly official Expanded Universe has been ret-conned by Lucasfilm into the canonically dubious Star Wars Legends. From now on, only the films and Star Wars: The Clone Wars are Holy Writ – which of course handily allows the new writers to repurpose any decent Expanded Universe bits they fancy for their own devices. How must that make the many fans that slavishly purchased all those books, comics, and what-have-you since 1983 feel?

Happy, they are not.

With regard to that other television sci-fi behemoth, Doctor Who, I never regarded the Big Finish audio only CD releases as ‘official’, even though they were licensed by the BBC. Auntie Beeb had also licensed the Virgin Publishing New Adventures print series (which I did not read; Sylvester McCoy, you see), or the later Missing Adventures (which I did). Seeing a potential profit, the BBC then took back the license when it expired and launched their own equivalents of the ‘new’ and ‘missing’ adventures, some of which referred back to the Virgin stories, while others flatly contradicted them.

It all became very confusing.

I took the attitude that anything broadcast on TV by the production team was ‘real’ Who, and the rest was whatever you wanted to make of it. However, this was complicated following the programme’s 2005 return when we started getting online only TARDISodes – little vignettes that acted as preludes and filler between the on-screen adventures. These had to count, surely? They were, after all, made by the official production team. Damn this multi-platform era. The situation was complicated further still when the 2013 fiftieth anniversary prequel ‘The Night of the Doctor’ saw Paul McGann’s (briefly) returning eighth Doctor name-checking all his Big Finish companions before regenerating into War Doctor John Hurt. Did that mean I had to buy all the CDs and listen to them?

Well, I didn’t.

Getting back to the Treksters, it seems to me that Roddenberry’s actions reflected a desire only to associate himself with respectable, grown up Trek. At the time The Animated Series was made, it was the only visible sequel to the original – but in the 80s The Next Generation changed all that. Although Roddenberry’s name was on the credits of the animated show as executive producer, he did not contribute any scripts – but then he hadn’t contributed much to the third season of the original show either, and was happy enough to be associated with that.

It all seems rather petty.

However, since Big Bird’s death in 1991 it has become clear that many later series writers in fact quietly regard The Animated Series as the real deal. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine referenced various races and places only ever mentioned in the animated version, and the re-mounting of Spock’s childhood bullying (albeit in a parallel timeline) for Star Trek (Abrams, 2009) could be read as a direct homage.

Poor little mite…

The fact that, following its DVD release in 2006, the series has now been incorporated into a fiftieth Star Trek anniversary BluRay set (including TOS, TAS, and the original cast movies) would seem to suggest that, at long last, it is firmly back in the family canon.

However, some still like everything to be clear-cut and above board, and it would be rather nice if an official announcement of some sort could be made. D.C. Fontana (always a stout defender of the animated show) would make an excellent spokesperson if CBS did decide to make it so, and for my money it would be a lovely nod if Discovery were to feature a cameo from the youthful Arex, in his first Starfleet posting.

Perhaps we could even purr-suade Jim Abrams to put M’Ress in the film series…

Dr Richard Hewett is Lecturer in Media Theory at the University of Salford’s School of Arts and Media. He has contributed articles to The Journal of British Cinema and Television, The Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Critical Studies in Television and Adaptation. His book, The Changing Spaces of Television Acting, will be published by Manchester University Press later this year.