I have long been interested in writing about performance in television and film and indeed when I turned to adaptations one of the things that interested me was how characters became embodied and took shape, on screen. But generally I tried to analyse performance through the text and look at how the actor moved and gestured, how facial expressions changed, how eyes moved. I knew something about different acting styles but very little about how an actor prepared. I was interested in what the viewer could see and respond to and tried to pin down what could be seen on screen.

Recently as more work has been done on acting I have been prodded out of this position and in this blog I report on two such prompts. The first was reading the interviews in Tom Cantrell & Christopher Hogg’s book Acting in British Television. Cantrell and Hogg’s analysis looks at the hidden labour of actors and challenges approaches like mine: ‘There is a long-standing critical tendency within screen acting research to prioritise the analysis of end performance products over an understanding of the professional or artistic processes on the part of the actor’ (p. 1-2). What they give us is a brilliantly entertaining read based on transcripts of semi-structured interviews with some major British television actors including Julie Hesmondhalgh, Nina Sosanya, Ken Stott and Rebecca Front. Each chapter groups together interviews about a specific genre – soaps, police and medical dramas, comedy and period drama – and a conclusion to each section provides an informed commentary.

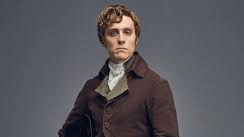

I found the period drama section particularly fascinating. For instance we are familiar with the conventions of such drama in terms of the country house setting, the elaborate costumes and the familiar upstairs/downstairs stories but to hear the actors reflect on how they perform in such situations is intriguing. Lesley Nichol who plays the cook Mrs Patmore (Fig 1) in Downton Abbey (2010-15) talks about how she worked with the historical advisor to makes sense of the character and used that to build up her relationship with the characters beneath her and those above her in the hierarchy. In turn this informs her gestures and movement in scenes with other characters like Daisy (Fig 2), the posture she would adopt, the emotional level she pitched at and the tone of voice. The kitchen scenes were particularly demanding because the timing and rhythms of a scene had to match the preparation of a meal. So ‘acting’ had to be done while she was carrying out credible kitchen work involved in cooking a meal (and taking advice from the chef in the props department) and the performance had to be consistent across the required takes: ‘We had to tip off new actors working in the kitchen about that pace’ she says, ‘you had to nail it very quickly and then repeat it’ she says (238). Jack Farthing who played George in Poldark (Fig 3) talks really interestingly about fleshing out a period villain in terms of using the historical research he did with the help of the advisor and the writer. Like Nichol he talks about the importance of the location and how details of the costume – the Malacca cane he carried – informed the internal creation of his characters. Such very precise details about how a character is created are found in all the interviews along with material about rehearsals, improvisation, ownership of the character and much else.

My second prompt to consider the practice of acting in more detail was a live interview at an RTS event with actor Stephen Graham who gave an emotional, ebullient account of his remarkable career. From Kirby, outside Liverpool, he enrolled at Everyman Youth Theatre and recalled watching Boys from the Blackstuff and Play for Today with his Dad: ‘kitchen-sink type of drama, which I used to adore. I always wanted to do that kind of work’. His first paid acting job was as a teenager in children’s drama Children’s Ward, which was developed for ITV by Paul Abbott and Kay Mellor at the very start of their writing careers. This year he will appear in The Irishman alongside De Niro, Pacino and Joe Pesci; it will be his third Scorsese role after Shang in Gangs of New York (2002) and Al Capone in HBO’s Boardwalk Empire (2010-14, Fig 4).

An account of the interview can be found at the Royal Television Society webpage and quotations come from that source. Two anecdotes stood out for me. Firstly, Graham spoke about how much he learnt from working with Shane Meadows as the racist skinhead Andrew ‘Combo’ Gascoigne in the 2006 film This is England and its later TV series on Channel 4 (Fig 5). In particular he explained that he found the role particularly hard because he himself is mixed race. Meadows had not known of his mixed heritage when he chose him for the part and Graham explained that telling him after the preparation for the film had begun was very emotional and he was worried about keeping the part. Graham’s grandfather came from Jamaica and so as a child Graham saw and experienced the racism his father had to face. He drew on the emotional memory of this experience of anger, resentment and shame to build up the racist character he was now being asked to develop; ‘that particular job was where I grew up as an actor’ he said. ‘It really [helped me to] understand the process completely . . . I really learned how to dive into a character.’ It was certainly a brave thing to do.

The second story concerned a scene he was filming with Al Pacino, an actor whom along with De Niro, Graham revered. The scene involved an argument and, without telling Pacino (though with a warning to the camera operator), on the fourth take Graham took a deep breath and improvised an action which involved him knocking a metal ice cream dish out of the star’s hand. A cut was called and Graham recalled how long the seconds seemed while he waited for Pacino’s reaction. Fortunately, Pacino, once he recovered from the shock, was pleased and excited and the gesture stayed in; he had to keep repeating it until his knuckles bled from knocking the metal surface. I was struck again by how committed Graham was to his craft and his way of working in the moment; it is like a lad from Liverpool going into the ring with the great US actor and imposing his own terms.

Of course work on acting as a process has been developing at a pace. Cantrell and Hogg have recently also published an edited collection called Exploring Television Acting and Richard Hewett’s The Changing Spaces of Television Acting is also out. I’m not sure how these accounts by the actors will have an impact on my own approach to analysis but they have certainly made me more aware of how actors can have their own agency and the precision they bring to their work.

Christine Geraghty is an Honorary Professorial Fellow at the University of Glasgow. Her publications on television include a contribution to the 1981 BFI monograph on Coronation Street; Women and Soap Opera (Polity, 1991); and My Beautiful Laundrette (IB Tauris, 2004). Her BFI TV Classic on Bleak House was published in 2012 and she has continued to make a major contribution to Adaptation Studies. She is on the editorial board of the Journal of British Cinema and Television and sits on the advisory boards of a number of journals, including Screen and Adaptation. Her most recent article on television is ‘What is the Television of the European Journal of Cultural Studies: reflections on twenty years of television studies in the Journal’, European Journal of Cultural Studies, 20:6, 2017.

References:

Tom Cantrell & Christopher Hogg, Acting in British Television, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Tom Cantrell & Christopher Hogg, Exploring Television Acting, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

Richard Hewett, The Changing Spaces of Television Acting, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2017.