When the creation of the BBC Written Archives Centre in Caversham was agreed, at a meeting of the Board of Management on 17 November 1969, it was done so with a view to history. Kenneth Lamb, then Director of Public Affairs, argued that the paper archives of the Corporation were of great value and interest to the public and the nation.

You may well have read about the ongoing campaign to reverse recent decisions at WAC – made by the senior archives team – that we believe act in opposition to the spirit of what a publicly-funded collection is for. I am a co-ordinator of that campaign, alongside Professor John Wyver and Dr Kate Murphy. A report for the Observer sets out the present situation clearly and accurately, but I want to tell you about the efforts made before we chose to go public.

Observer report from 24 August 2025

Back in February, researchers noticed that the language was being altered incrementally on both the BBC Heritage page and WAC’s auto-replies to email enquiries. There was talk of a ‘new model’ for the release of files. No longer would users be able to request files according to their research needs and have them vetted (or ‘opened’). This had stood for decades. It was central to the archive’s deserved reputation as a vital place for social, cultural and political research of all types.

Other changes included a reduction in visitor days from three days per week to just two, and a complete shutting of the door to the general public, i.e. licence-fee payers. Many of these policies were presented last year as temporary measures under the guise of an ‘audit’, but they are now permanent. There was no consultation.

The BBC will now decide what is released and when. It will be driven by a mixture of business interests, content for its platforms, and – in their own words – an avoidance of risk.

Clearly, this is the opposite of how research works. Any historian can tell you that information is rarely found all in one place. Pursuing the full story is done by following leads, through unexpected avenues of the collection, often hitting upon papers which are not even the copyright property of the archive. One recent example is a piece of research I began last year, just before the shutters fell, which now calls for me to look at an associated file. I was told last week it is not ‘open’ and is therefore unavailable. The information in that file is probably lost to me for good.

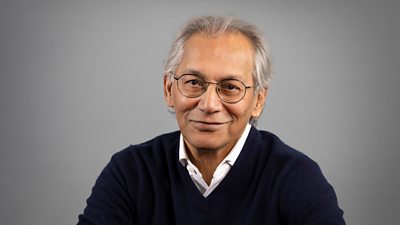

Two thirds of the paper archive – typically production documentation, copyright and contributor files – are presently unavailable to researchers. Our campaign began to query this, first in writing to Dr Samir Shah, the BBC Chair, and then in conversation and correspondence with the senior staff who made the changes. They boasted that au contraire, the availability would expand from 30% to 50% in just five years, but despite many exchanges on the matter we are completely in the dark as to what this extra 20% will actually comprise. What we can be certain of, however, is that it will not be aligned to user demand.

Samir Shah, chair of the BBC

We were told in April that this was part of a nine-month process and the conversation would continue. Much stalling from the BBC side then ensued.

At a meeting in mid-August, where a number of scholars met with the current Lead Curator, it was made clear that the BBC’s position had hardened. The decision had been made, it was agreed by those higher up, and it was a done deal. This felt like a moment of bad faith and that is why we went public the following week with an open letter, now signed by over 500 writers, researchers, historians and former staff.

As it states, the policy changes are a catastrophe for books, articles, PhDs and documentaries. Lecturers can no longer recommend WAC as a resource to students. I myself often work with bereaved families who are looking for a depositary for the archives of recently deceased BBC staffers and contributors. I can no longer recommend WAC as a home, and at the August meeting I told the Lead Curator so.

So what can we expect from the BBC? In the Observer the press office spoke of ‘content moments’ to celebrate individuals and anniversaries – a bit like this – but that icky phrase does rather suggest you will get very little and you will have to make do. The irony that these ‘content moments’ will often rely on the initiative and writing of past WAC users is inescapable, but try telling that to the BBC. We did, several times.

This is so sharply out of key with the work of comparable archives that it raises serious questions about whether the BBC remains a fit and proper keeper of its own collection. There is no online catalogue, which in itself makes WAC something of an outlier. A catalogue was funded and developed over several years, and formed a part of forward planning as late as 2023, but was quietly ditched. No one really knows why.

Cutting days, cutting off access to files, cutting out the general public, is not a route to securing a service for the future. Unless the true intention is to destroy the service slowly in order that it be closed to the public altogether.

Solutions exist. Increasing charges to production, which constitutes much of WAC’s back-of-house work, would be a start. Other archives have a ‘volunteer army’ of retired experts who can vet responsibly. A relocation of parts of the collection, and staff resources, to other public archives is worth exploring, too.

Just as a cost-cutting measure – the surface motive – it is short-sighted and demonstrates a lack of understanding of archive value. The overall cost benefit of independent and exploratory research is through books, articles, documentaries, and the soft power it brings. The hard work of people who are telling those stories on the BBC’s behalf comes at no cost to the organisation itself. Indeed, they charge authors for quotations.

Cynics and pessimists will suggest that group actions are doomed to fail, but we would argue that collectively we have got a response from the BBC’s Chair, meetings with the decision-makers, and publicity as well as a spreading-of-word throughout the research community that simply wouldn’t have emerged via individual complaint. That said, we encourage everyone to write to heritage@bbc.co.uk to express their concern. We can assure you these messages are read by the people in charge of this decision.

Beyond the meetings and correspondence we have had, it is all speculation as to why this set of changes has been driven through. Director-general Tim Davie is known to be interested in monetising absolutely every aspect of the BBC; a ‘public library’ doesn’t really fit in with that. But then look at the Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology who wrote in January that the BBC, British Library and other national archives should be used for their ‘valuable cultural data’ in the development of AI. Perhaps the increase to 50% of available papers within the next five years is to fatten the pig?

Tim Davie, the BBC’s director-general

What is clear is the BBC’s retreat. BBC Sounds has been curtailed abroad. The searchable Genome archive of Radio Times is no longer attended to and now frequently falls over. The ability of members of the public to return missing programmes has become too arduous. Creatives’ access to BBC Archive Search has been reduced considerably. In step, the WAC is freezing its own files for its own purposes and no one else’s.

As was clear from Davie and Shah’s appearance in front of the Select Committee for Culture, Media and Sport on 9 September, most of the oxygen around the BBC has been taken up by high-profile controversies over Gaza, Glastonbury, and Gregg Wallace. In that context what we are asking for may seem niche, yet it should be key to how we receive the story of the BBC.

The BBC wants to have it both ways – to celebrate its centrality to society and culture for more than a century, while at the same time removing itself from the process of that same story being told accurately, fully and fairly. It would be wise not to alienate the very community that can help them the most. Davie’s self-expressed credo for the BBC is “pursuing truth with no agenda”, but the culture he has now created is making that impossible for researchers.

We are at a crossroads in the future of research in the UK, and the BBC’s high-handed changes at WAC are taking us backwards not forward. The WAC should be cherished and protected in the Charter Review. Over the next few weeks, a series of guest bloggers and signatories of our open letter will explain why they think the BBC is throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Please join us and sign the letter by writing to bbcwaccampaign@gmail.com .

Ian Greaves has published widely on television history. His new book is Penda’s Fen: Scene By Scene, published by Ten Acre.