One of the key talking points at this year’s RIPE conference – an event attended by industry and academia – was the issue of how public service broadcasters can continue to compete in a marketplace dominated by global players such as Netflix, Amazon Prime and Disney+. These are platforms with deep pockets (although a lot of that is debt), big-budget productions and subscriber bases that dwarf the PSBs’ own limited domestic reach. For example, it is estimated that 209 million households now have a Netflix subscription, whilst BBC iPlayer only has a potential domestic reach of some 28.1 million households. To put that another way, BBC iPlayer’s audience is only 13.4% the size of Netflix’s audience.

As PSBs go, the BBC is relatively large (if we’re measuring it in terms of domestic audience). Other PSBs, however, operate on a much smaller scale than the BBC and therefore their task is made all the more difficult. DR in Denmark, for example, has a potential audience of just 2.7m households. How are they to compete with the Goliaths of Netflix, Amazon, Disney+ et al., whose economies of scale are even larger in comparison to theirs?

One answer is: don’t try to compete. After all, PSBs have very different objectives, address different kinds of audiences and issues, produce many genres not commonly found on SVODs (news, current affairs, soap operas, weather, sports, etc.) and offer various other non-film/TV related content (e.g. news journalism).

However, the reality is that PSBs are still competing for the same eyeballs, and thus it would be naïve of them to rest on their public service laurels. Moreover, with the BBC about to celebrate its centenary and other PSBs about to reach important milestones (DR will soon join the centenarian club, whilst Channel 4 will be 40 next year) there is a heightened discourse around the continued role and relevance of these institutions, creating further pressure for PSBs to legitimise their own existence.

So how do they adapt? How do they retain their relevance and their position in this increasingly competitive marketplace? In this post, we examine two recent and quite different examples of how public service broadcasters are responding to these challenges.

DR: Small, Danish and soon to be fully digital

In response to this need for reinvention, DR (Danish Broadcasting Corporation) recently revealed their “digital first” initiative. Announced in October of this year, it represents a major shift in how DR will now operate, so much so that experts have described this initiative as “historic” and “cataclysmic”. Besides some significant organisational changes, the paramount innovation is that content across all genres is to be developed and produced to be published on digital platforms. What this means in practice is not fully clear – will drama series be released all-at-once as they often are on SVOD platforms? Will current affairs magazines be available as ‘VODcasts’? What we do know is that linear radio and television channels will be kept in service as long as they are being used, but the on demand-service DRTV is intended to be the front door to all of DR’s services. To our knowledge this makes DR the first public service media (PSM) institution to pursue such a strategy. However, all over the world legacy media are, at differing speeds, participating in this same transition to become more (if not fully) digital, not least to keep pace with digital-only, data-driven platforms such as Netflix.

But why specifically do we see this development in Denmark and why at the PSM DR? DR justifies its strategy by stating that the Danes are not becoming digital, they ARE digital (DR 2021, p. 10). If we look at the numbers, this is not an exaggeration. Between 99% and 100% of Danish households now have access to the internet, and whereas the weekly reach of flow TV has fallen from 77% in 2018 to 72% in 2020 the reach of streaming TV has increased from 57% in 2018 to 68% in 2020. In short, Denmark is primed and ready for such an innovation.

Fig. 2: DRTV: DR’s online streaming platform which is central to their new “digital first” strategy.

This move is interesting for a number of reasons. Not only does this “digital first” strategy represent an attempt by DR to adapt to an increasingly “digital first” world, but it also marks the beginning of a more independent DR: more specifically, it is a version of DR that is more independent of the BBC. For decades the BBC has been the Mothership of all public service broadcasters, including DR. Provocatively one could say that whatever the BBC did, DR would soon follow suit. This Includes the launch of youth-oriented channels (BBC Three / DR3) and the transition of said channels from linear to online only.

But now these PSBs are heading in different directions. In November, representatives from DR and the Danish broadcaster TV 2 met with head of BBC Three, Fiona Campbell, for a discussion in Copenhagen. One of the key items on the agenda was the strategic decision behind the return of BBC Three as a linear channel. What Campbell explained was very much in line with the reasons behind DR’s launch of its digital strategy: PSM organisations are obliged to be present on the platforms most used by the population. And whereas DR is reinventing itself for a population of digital users, the BBC finds that there is an opportunity audience that is not being reached by the existing offer on iPlayer or current linear channels (see also BBC 2020, p. 24). Thus, we see this – perhaps rather unusual – step backward for the BBC in which they are increasing their offline/linear presence. However, as Campbell emphasized to listeners in Copenhagen: BBC Three’s strategy is still digital. And while there will be a linear BBC Three channel once again, BBC iPlayer is to be prioritized as a key destination for their content, at least for the next five years.

BBC: Big, British and more data-driven

Whereas DR’s “digital first” approach involves a wholesale restructure, the second example we want to explore is a somewhat more restrained and certainly more hypothetical one (given that it is simply proof-of-concept at this stage): namely, the BBC’s recent experimentation with combining different datasets in order to create more personalised user experiences. Indeed, there is little doubt that these experiments are a direct response to the growing threat of SVODs, with Wired describing it as “a radical new data plan that takes aim at Netflix.”

Whilst personalisation is a key and highly valued feature of SVODs, it is somewhat more problematic in the context of public service broadcasting. As critics have noted, the very notion of personalisation doesn’t necessarily align with the aims and objectives of PSBs (Sørensen and Hutchinson 2018). Nevertheless, the idea of a public service algorithm is a powerful and enduring one. Both the BBC and DR have been exploring the possibility for years, speaking publicly about their intentions to develop such an algorithm as far back as 2017. The notion of a public service algorithm was also a frequent point of discussion at RIPE, the consensus being that it is as an urgent and inevitable development for PSBs – a necessity if they are to compete with the SVOD Goliaths. What a public service algorithm could be or how it might work is still up for discussion, but there is a general agreement that it should not follow the same principles as a commercial, off-the-shelf algorithm.

Whilst the notion of a public service algorithm requires further explication, these PSBs need data, and lots of it, before they can even begin to develop or operationalise such a feature. Once again, Goliath (the SVODs) has the upper hand over David (the PSBs). If BBC iPlayer reaches around 1/10th of the number of households that Netflix does, it’s safe to assume that the amount of data that the former can gather pales in comparison to the latter. This is significant because in data science the general principle is that the more data you have the more effective the algorithm will be (though there are always exceptions to this, and a good algorithm is better than bad data). As Jockum Hildén points out, popular methods such as collaborative filtering may not work for smaller platforms as these types of algorithms ‘require a lot of users and a lot of content to work properly’ (2021:3). And as we know, users of public service platforms are often reluctant to accept the basic cookies that makes this kind of data collection possible in the first place (Lassen and Sørensen, 2021).

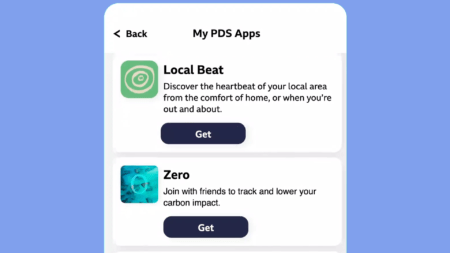

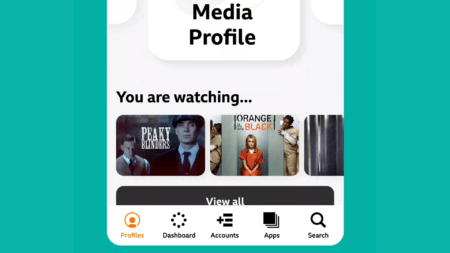

Without economies of scale on their side, the BBC have had to think outside the box. Rather than following the SVOD mantra that bigger data is better data (it isn’t always better), the BBC have focused instead “on reinventing how data is stored, processed and controlled online – changing how people think about and use personal data.” At the heart of this project is an experimental system that draws on a range of different personal user data taken from three different platforms: Spotify, Netflix and BBC iPlayer itself. Whilst this “personal data pods” (PDP) project it is simply a proof-of-concept, it demonstrates the importance of data for PSBs in an increasingly data-driven world. More than this, though, it is clearly an attempt to empower users and to deliver new kinds of public service values through their own data – something that is not necessarily in the interests of SVODs.

Fig. 3: Mock-ups for the BBC’s recent Personal Data Pods Project. Note the presence of Netflix titles …

Conclusion

Though both these examples of reinvention are very different in terms of scope, scale, and ambition, they both provide evidence of the need for PSBs to adapt in order to ensure their continued relevance in a rapidly changing media landscape. Moreover, despite their differences, both examples ultimately put these PSBs in a stronger position when it comes to data – a key currency and key infrastructural asset in our increasingly “digital first” world. DR, for example, will generate much more data as a by-product of their “digital first” initiative. Meanwhile, the BBC’s PDP project is a clear attempt to increase and diversify their data assets in order to improve the user experience and compete with SVODs. In this way, both PSBs might finally be able to realise that elusive dream of a public service algorithm, whatever that might eventually be.

But these attempts to accumulate and leverage data are just one part of a bigger project of ongoing public service reinvention – this isn’t the first time PSBs have had to adapt, and it won’t be the last. What we see in these examples is that the one-size-fits-all approach of Netflix doesn’t make sense for national PSBs such as the BBC and DR who are pursuing very different strategies. Instead, this ongoing reinvention of public service broadcasting must respond to the specific demands of each national context, with bespoke approaches that match their unique technological infrastructures, demographic profiles, media habits, and so on. Perhaps this is one reason they will survive. Their diminutive size is a strength rather than a weakness, making these PSBs more nimble, more flexible, and more able to adapt. For this reason, David stands a good chance against Goliath.

JP Kelly is a lecturer in film and television at Royal Holloway, University of London. He is the author of Time, Technology and Narrative Form in Contemporary US Television Drama (Palgrave, 2017). He has published essays in various books and journals including Ephemeral Media (BFI, 2011), Time in Television Narrative (Mississippi University Press, 2012), Convergence, Television & New Media, Critical Studies in Television and MedieKultur. His current research explores a number of interrelated issues including narrative form in television, digital memory and digital preservation, and the relationship between TV and “big data”.

Julie Münter Lassen is a postdoc at Media Studies, Aarhus University, Denmark. In her PhD dissertation she studied the development of the television channel portfolio of DR in a period characterized by channel proliferation (see also Lassen 2020). Her ongoing research interests are public service media and the transition from traditional broadcast media to on demand platforms. She currently works on the project Re-Scheduling Public Service Television in the Digital Era, which focuses on how two traditional Danish public service media organizations adapt to the challenges and conditions of the digital media landscape.

References

DR (2017): “Redegørelse vedr. befolkningens brug af on demand samt erfaringer med DRs tilrådighedsstillelse af tv-programmer on demand” [Report on the population’s use of on demand, and experiences with availability of DR’s TV programmes on demand]. https://dr.dk/static/documents/2017/06/14/redegoerelse_om_dr_tv_aa65a3b7.pdf

DR (2021): “DRs strategi frem mod 2025: Sammen om det vigtige” [DR’s strategy towards 2025: Sharing the important]

Hildén, Jockum (2021): “The Public Service Approach to Recommender Systems: Filtering to Cultivate”. Television & New Media. P. 1-20. DOI: 10.1177/15274764211020106.

Lassen, Julie Münter and Sørensen, Jannick Kirk (2021): ”Curation of a Personalized Video on Demand Service: A Longitudinal Study of the Danish Public Service Broadcaster DR”. ILUMINACE, Vol. 33, no. 1 (121). P. 5-33.

Sørensen, Jannick Kirk and Hutchinson, Jonathon (2018): “Algorithms and Public Service Media”. In: Gregory F. Lowe, Hilde Van den Bulck and Karen Donders (eds.): Public Service Media in the Networked Society. Göteborg: Nordicom. P. 91-106. https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1535645