I started my career studying and writing about television and children by watching my own children watch television and becoming very intrigued about the views of the world they were being shown in the preschool programmes they saw. I wasn’t alarmed or disapproving – just intrigued, also very entertained. I was a freelance journalist at the time and my first published article on this subject was called ‘Feudalism for the Under Fives’, and it appeared in The Listener magazine (published weekly by the BBC) in 1977. [1]

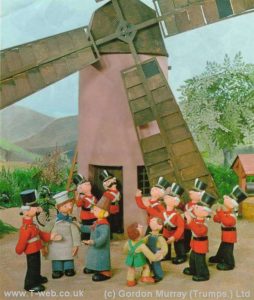

In those days, without the option of downloading, time-shifting, DVD copies or boxed sets, there was little opportunity for children to see repeated viewings of the same material. Nevertheless, throughout the 1970s there were three little TV shows that seemed to turn up every few months, in rotation, which my young children watched avidly, forcing me to become aware of the sociological representations being repeatedly offered to them. These shows were: Camberwick Green, Chigley and Trumpton, to which I gave the generic heading Trumpley Green. [2] Chigley had a Lord who lived in a castle with a butler, and who drove a steam engine. Camberwick Green was a village with tradespeople and housewives and a redcoated regiment of soldiers. Trumpton was a town with a mayor and a famously underused fire-brigade, Pugh, Pugh, Barney McGrew, Cuthbert, Dibble and Grubb.

My intrigue partly arose from the blithe mixing together of very diverse and anachronistic social and historical institutions, behaviours and costumes. What did my young children think a Lord was? What is a butler? What is a mayor? Why do women in long dresses work in a factory? Chigley was mildly industrialised – it had a biscuit factory with male and female workers, and at the end of the day they all came out and danced together. Windy Miller had a wind-powered windmill; contrastingly, Pugh and co drove a motorised fire engine. At what point in history did all this take place? And where? To be frank, I now don’t think the answers to any of these questions matter much – certainly not to the children, who took from it what they liked, and to this day, (now in their 30s and 40s) can recite ‘Pugh, Pugh’, and ‘time flies by when you’re the driver of a train.’ But as the television scholar I later became, (thanks to the arrival of my fourth child, which stimulated me to do a part-time PhD studying television audiences), and as a fairly recent grandmother of small children, I am now revisiting these early musings and coming up with similar questions. I do think these questions about the meanings of the tropes, conventions, innovations, oddities, experimental doodlings, inconsistencies, nonsenses, techniques, aesthetics and catchy tunes of preschool television are worth asking. It’s most important, of course, to understand what they mean to the little people who watch them so compulsively.

My intrigue partly arose from the blithe mixing together of very diverse and anachronistic social and historical institutions, behaviours and costumes. What did my young children think a Lord was? What is a butler? What is a mayor? Why do women in long dresses work in a factory? Chigley was mildly industrialised – it had a biscuit factory with male and female workers, and at the end of the day they all came out and danced together. Windy Miller had a wind-powered windmill; contrastingly, Pugh and co drove a motorised fire engine. At what point in history did all this take place? And where? To be frank, I now don’t think the answers to any of these questions matter much – certainly not to the children, who took from it what they liked, and to this day, (now in their 30s and 40s) can recite ‘Pugh, Pugh’, and ‘time flies by when you’re the driver of a train.’ But as the television scholar I later became, (thanks to the arrival of my fourth child, which stimulated me to do a part-time PhD studying television audiences), and as a fairly recent grandmother of small children, I am now revisiting these early musings and coming up with similar questions. I do think these questions about the meanings of the tropes, conventions, innovations, oddities, experimental doodlings, inconsistencies, nonsenses, techniques, aesthetics and catchy tunes of preschool television are worth asking. It’s most important, of course, to understand what they mean to the little people who watch them so compulsively.

Which brings me up to date with some recent experiences. Thanks to the companionship of a now six year old granddaughter, my son’s daughter, and another nearly two year old granddaughter, my daughter’s daughter, I have been observing the next generation and their current obsessional viewing patterns – patterns made much easier by their favourite programmes’ availability on download, YouTube, or on DVDs. The two year old is obsessed with Woolly and Tig [3] which she watches on YouTube on an i-pad, or sometimes, when her parents can bear it, on the big family TV. During a recent spell in hospital, very listless and lacking in energy, the first thing she asked for when waking up after a refreshing sleep was ‘Tig.’ The six year old, having been through stages of being obsessed with In the Night Garden, Thomas and Friends, Bing and more recently The Worst Witch, now watches Disney’s Moana [4] over and over again. Why?

The fact that the children insist on repeated viewings, often in my company, is certainly an advantage to the scholar: there is always something new to notice. My musings about what is going on, at this stage are purely speculative rather than rigorously scholarly. I’m just speaking as an interested relative – which of course, is where I came in, all those years ago. But scholarly interest has also been stimulated by recently reading some research by Cary Bazalgette, studying the reactions of her two year old twin grandchildren to TV-watching experiences. The full study is not yet published, although details can be found at her website. [5] (See also previous writings such as Bazalgette, 2010.)[6] As with me, years ago, so with her: questions of meaning, comprehension and emotional effect were triggered by observing both the programme content and the toddlers’ reactions to it. Her initial interest was sparked by a fear reaction to In the Night Garden: “the defining moment that got me started on my doctoral research was seeing my 13-month-old grandchildren terrified by the episode of In the Night Garden in which Mr Pontipine’s moustache flies away.”

So this got me wondering about Woolly and Tig. Woolly and Tig is a short, live action, documentary programme about everyday experiences which pose a challenge to the three and four year old little Scottish girl (Tig) who is experiencing them. Tig is an only child with an attractive, middle-class mother and father and she lives in a very pleasant house somewhere in Scotland. The Scottish voice-over narrative is Tig as an older child; it always begins: ‘When I was little…’ And then the adventure – the hair-washing; the trip on the subway; the sleepover at a friend’s house; the chicken pox and so on – begins. Tig always has some kind of a problem with these experiences – hating her hair being washed; being homesick; having itchy spots – which is where her toy spider, Woolly, comes to the rescue and explains why these things are necessary, and how Tig’s feelings are normal. According to the consultant psychologist for the programme, Dr. Martin Williams, “‘Woolly and Tig’ is an aid to understanding the ‘self’ . . . Anger, jealousy, fear, sadness are just some of the feelings explored in a simple, fun and positive way.” [7] Why a multi-coloured, animated Woolly spider, whose voice-over sounds like a small boy from North London, should be the chosen guide to an anxious Scottish three year old is not explained, but it surely does work for our little S, who currently lives in neither Scotland nor North London, but in Brooklyn in the USA. ‘I love Woolly and Woolly loves me’, as the theme song goes – that’s the main thing for S at the moment. The programme seems to provide repeated reassurance that life will be manageable and there’ll always be help at hand, from beloved transitional objects, as well as from adults.

Six year old L has reached the age when she can dress up as Moana, have Moana jewellery, and play the Moana theme tune and songs on a MP3 player repeatedly sometimes to the distraction of everybody else. Moana is not a TV show, but a feature film produced and distributed by a huge, international corporation, not, as with Woolly and Tig, by a small independent production company commissioned by a public service broadcaster, the BBC. This is a distinction that means little to L, although such is her inquiring frame of mind that I have no doubt that, at some stage, she will give me a lecture on the Disney Corporation, after carefully scrutinising the film credits – which, as a new reader, she likes to do. But the domestic viewing experience for her is no different from her dad’s experience of watching Camberwick Green – L watches Moana on a DVD on the family television set in the company of her family.

What’s so special about Moana? Unlike L, who has a two year old brother, Moana is an only child – and she goes off in a sailing boat to have adventures beyond some dangerous reefs, which the rest of her Polynesian island society are afraid to do, in order to save the island’s threatened eco-system. Moana is inspired by her grandmother, a rebellious spirit, who dies in the course of the action and returns as a stingray to guide Moana at particular moments of peril. L often expresses concern about the death of elderly relatives (two have died in her recent memory) and it’s possible that one of the many attractions of the story is that it says something reassuring about death. L asked me if, when I die, I could come back to accompany her – which I surely would love to be able to do, if not as a stingray. Whatever the reasons for L’s concerns, Moana’s grandmother provides a good, strong, mature woman as role model in the movie and this seems important for L. The unfamiliar Polynesian setting, another of Disney’s attempts at multiculturalism, is taken as given: what matters to L is the relationships and the adventurous spirit of the heroine, also an increasingly sophisticated appreciation of the animation and special effects. This is the advantage to a child of repeat viewings over time, an advantage less available to earlier generations of viewers. L has been allowed to use the material to develop different meanings and responses for herself as she watches them again and again, and is able to point them out to me, as a less experienced viewer.

Speaking for myself, I will never stop being interested in how our young children relate to audio-visual storytelling because it tells me something unique about them, and because it’s an experience that we can share and enjoy together. It also reminds me that my original sociological approach to the content of programmes – anxiously wondering if children were aware of social hierarchies, inconsistencies and stereotypes – are adult questions which do not seem to be central to very young children. For them, flying moustaches, stingray grandmothers and cheerfully reassuring chatty toy spiders are currently more salient.

For the time being, Tig’s toy spider, Woolly, is offering little S repeated reassurances about the domestic and outside world she is becoming increasingly introduced to. Moana is an exciting, morally uplifting story, offering an adventurous role model to an imaginative, bright little girl who lives in the very different environment of a big city, and it has very catchy songs which she loves. As with the music of Camberwick Green and its companions, music and song should never be underestimated as having lasting value and pleasure for young children – the importance of sound was another feature of preschool material emphasised in Bazalgette’s research. I dare say L will one day be singing Moana’s song to her own children, if she has any, and S will be reassuring the doctors treating her little ones, if she has any, and who recoil from Woolly, ‘Don’t worry, it’s only a toy spider.’

Let us hope that when that day comes, there will still be the financial resources and the political will for talented storytellers to produce programmes and movies that help young children to cope with the challenges of life, and to stimulate their imaginations and that there will still be the means to distribute them generally to whoever needs them, at little cost to them. But that’s another story. (See Steemers 2017 [8]).

Máire Messenger Davies is Emerita Professor of Media Studies at Ulster University, and a Visiting Professor at the University of South Wales. She has a BA degree in English from Trinity College Dublin and, after a journalistic career in local newspapers and national magazines, she obtained a PhD in psychology at the University of East London, studying how audiences learn from television. She has worked at Boston University and at the University of Pennsylvania in the USA, and later, in the School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies, at Cardiff University. She specializes in the study of child media audiences, and is the author of several books including Children, Media and Culture (McGraw Hill/Open University, 2010); “Dear BBC”: Children, Television Storytelling and the Public Sphere (Cambridge University Press, 2001), Television is Good for Your Kids (Hilary Shipman, (1989, 2002) and, with Roberta Pearson, Star Trek and American Television (University of California Press, 2014.) She has four grownup children, and three grandchildren. She lives with her journalist husband in Cardiff, Wales.

References:

[1] See http://gale.cengage.co.uk/product-highlights/history/the-listener-historical-archive.aspx

[2] See http://www.t-web.co.uk/trumpchg.htm

[3] Woolly and Tig (2012), (UK) production companies

- TattieMoon

- The Charactershop Ltd.(produced in association with)

- Distributors

- BBC Worldwide(2012) (UK) (TV)

- Abbey Home Media Group(2013) (UK) (DVD)

- CBeebies(2012) (UK) (TV)

[4] Moana (USA) (2016) Walt Disney Animation Studios

[5] See http://toddlersandtv.blogspot.co.uk

[6] Bazalgette, Cary (2010) Extending Children’s Experience of Film. In Teaching Media in Primary Schools, ed. C. Bazalgette. London: Sage.

[7] From 2014 CBeebies website, Grownups page (no longer available)

[8] Steemers, Jeanette, (2017) International perspectives on the funding of public service media content for children, Media International Australia 2017, Vol. 163(1) 42–5. DOI: 10.1177/1329878X17693934