I’m sure that at a certain point people are going to get bored of me worrying at the question of what and who television history is for (if they aren’t already). Speaking as someone who occasionally describes themselves as a television historian, you may see this as a form of existential angst, a near-obsessive need to examine and justify the thing that I spend the majority of my day doing. However, thanks to the editors of CST inviting the ‘History of Television for Women in Britain, 1947-89’ team to occasionally contribute to this blog, I want to return to this question again, so bear with me.

Last week, the BBC4 documentary Tales of Television Centre (tx. 17/5/12) offered a nostalgic look at the West London home of the BBC, two years before the broadcaster finally vacates the building. A 90-minute programme combining talking-head interviews with a myriad of television performers and producers, interspersed with archive footage of the building’s appearances in programmes throughout its history, it has been described in press reviews as a ‘nostalgic, ribald homage’ (Radio Times), a ‘self regarding wake’ (Telegraph), and ‘fabulously self-indulgent’ (Independent). The notion of ‘fabulous self-indulgence’ as a description of the telling of television’s history interests me. Television is often seen as an indulgence in and of itself, a luxury rather than a necessity, so couldn’t reflecting on, documenting, recording its history be seen as the pinnacle of profligacy?

Tales of Television Centre was produced and directed by Richard Marson, the producer who was famously sacked as producer of Blue Peter as a result of the ‘naming the kitten vote rigging’ scandal, but who is more interesting as a historian of popular television, producing books and programmes on the history of long-running programmes such as Upstairs Downstairs and Blue Peter. Marson’s pedigree as a ‘BBC man’, working his way through the ranks of Television Centre-produced programmes such as That’s Life!, Going Live, and Top of the Pops, certainly makes an impression on the programme. It is both rich with the detail of the production history of BBC television, and also often feels rather like one of the ‘Christmas tapes’ described in the show, an edited tape of bloopers and irreverent performance by BBC stalwarts produced by the VT Department for in-house consumption only. By this I mean that one gets the sense that this programme is both speaking about, to and for the large numbers of BBC workers who have spent their careers in Television Centre, reminding us of the distance between us, the viewers, and them. The interviews Marson solicits from his subjects suggests an intimacy and warmth produced by the sense of a shared history, a history in which the viewer did not participate, but rather experienced from afar. The final montage sequence of the programme, in which the great and good of the BBC (David Attenborough, Joan Bakewell, Esther Rantzen et al) offer a single word to camera to describe Television Centre, might be seen as the pinnacle of the programme’s elegiac self-indulgence, set to music (which I’ve been unable to identify, but which I’m certain will be a familiar theme to others) which evokes a sense of loss and regret.

Some of the adjectives used in this sequence (‘historic’, ‘influential’) speak of the Centre as a space that reflects that version of history, and BBC history in particular, which is all about the ‘great deeds of great men’, a history which, to a large extent, was focused on in the BBC’s earlier documentary about its own history, Auntie: The Inside Story of the BBC (BBC1, 1997). Many more of the words used to describe the studios (‘terrific’, ‘exciting’, ‘extraordinary’, ‘magical’, ‘wonderland’, ‘Shangri-La’) suggest a space of wonder, evoking an image of television production as out-of-the ordinary, as something that happened outside of ‘real life’, keeping the ‘us and them’ line firmly drawn. In this sense, the documentary offers the viewer an insight into television’s production history which is insistently ‘mystical’, and might be seen as taking us into an iconic space to which a relatively privileged few had access. However, what I liked about the documentary can be summed up by the words chosen by others to describe Television Centre (‘warm’, ‘family’, ‘home’) and by the comments from Babs Lord (‘It’s like coming home – it played such a big part of our lives’) and Sarah Greene (‘There’d always be friends in there and there’d always be gossip’) included in this sequence. Whilst one might want to argue that this is pure and simple nostalgia, providing a sentimental vision of a bygone era of television production, I think it, and the programme more generally, gives us more than this. What this feels like to me is an attempt to portray the feelings of television history at a key moment in the medium’s history, a telling of the emotional history of a production space and an attempt to capture the quotidian nature of the BBC’s production history. Television production is, literally, daily in the sense that it takes place every day, just as television viewing is daily: whilst there have been analyses of the latter type of dailiness since the formation of television studies as a discipline, much less attention has been paid to the former. Therefore, an attempt to capture the ‘ordinary life’ of television production in a very specific time and place, within the context of a light documentary being shown on BBC4, might be welcomed by academic historians rather than being shunned and dismissed for being ‘pure nostalgia’. This argument brings to mind calls for a reexamination of the role of nostalgia in television histories from Lynn Spigel (in her article ‘From the dark ages to the golden age: women’s memories and television reruns’, Screen, 36/1, 1995) and in television’s history in Amy Holdsworth’s brilliant book Television, Memory and Nostalgia (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). It also had a particular resonance for me, and for the ‘History of Television for Women in Britain, 1947-89’ team, because we have been spending a great deal of our time over the last month in thinking about nostalgia, about the role it plays in our work, and the uses of nostalgia evoked by our work in the field of television history.

For those not familiar with this research project, it is running between Warwick and De Montfort Universities from 2010 to 2013, and explores and documents the history of television produced for a female audience in Britain, from the re-start of regular television broadcasting in Britain after World War Two, to the end of exclusively terrestrial broadcasting in 1989. We are looking at both the programmes that were made and the production contexts from which they emerged, but also at the experiences of the women who have watched this programming. In broad terms, the Warwick team are exploring the programmes and production culture of this period, whilst the De Montfort team are conducting an audience study, interviewing a generationally and nationally-dispersed group of British women about their memories of watching the television that they perceived as having been ‘for them’. As we had expected, sometimes, this is not quite the same thing as ‘women’s television’. In terms of genre, sport and music television have been brought into focus in ways we could not have anticipated.

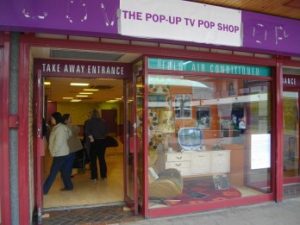

Given our focus on both ‘ordinary television’ and the memories of ‘ordinary women’, we have been looking for unorthodox ways to present our historical research back to a ‘general audience’, beyond the confines of academia. Whilst this might be seen as a response to the context of the REF and the subsequent increased vigor with which UK university research has been addressing an ‘impact agenda’, the project actually pre-dates this agenda and had been designed with this kind of two-way conversation in mind from its inception in 2004. This was, of course, also informed by my, and my colleagues Rachel Moseley and Helen Wood’s, worrying at the question of ‘what and who television history is for’. The result of this desire to situate our research within an ‘everyday space’ and to talk to the general public about the research and about their memories of television was a pop-up exhibition and ‘drop-in’ shop in Coventry city centre focusing on the history of British pop programming, one of the striking themes of our audience research: The Pop-up TV Pop Shop. As mentioned above, music on television had arisen as a key area for discussion in Hazel Collie’s audience research in ways we hadn’t initially anticipated: interviewees have been especially keen to talk about viewing pop programmes, about their importance in keeping up with (and recording) the latest trends in pop music and fashion, and their impact on their evolving identity as teenagers and young women (particularly around key programmes such as Ready Steady Go, Six Five Special, Top of the Pops and The Tube).

The Coventry arts organisation Artspace brokered a deal with Coventry City Council through their ‘Empty Shops’ initiative (recently praised in Mary Portas’ high street review), to house the project team’s exhibition about their work in a disused cafe in Shelton Square in Coventry city centre throughout May 2012. Shelton Square is a relatively run-down area in the city centre: it mainly houses small local business, and hasn’t attracted any large high-street chain stores. It is adjacent to the indoor market and away from Coventry’s main shopping centres. The exhibition made use of the large shop window (and the inside of the shop) to display an exhibition of props, documents, and moving-image footage to evoke the history of this programming in this period, and to get the passing public thinking and talking about the pop programmes that were important to them.

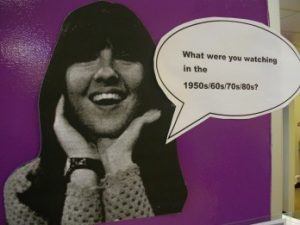

We opened the shop three times a week so that members of the public could drop in to talk to the project team about their work and share their memories of television viewing in this period, as well as looking at the items on display. Visual prompts throughout the shop, placed alongside images from listings guides in which pop television featured, a collection of TV ephemera from the postwar period, and furniture, clothing, and objects which evoked a 1960s living, asked the visitors to talk to us, and each other, about their memories of television of this era, and to share their thoughts and memories of pop programmes in particular.

In addition to talking, visitors were encouraged to add their memories on cards to pin boards on the wall, and/or to a visitors book.

This is a technique for memory gathering we had witnessed around the question of television viewing in other local museums: the National Space Centre in Leicester invites visitors to write down their memories of the watching the moon landing and other television of the period in a mocked-up living room set,

whilst the Herbert Gallery and Museum in Coventry asked visitors to write down their memories of watching Coventry’s cup final win in a recent exhibition on this subject. This was, however, our first experience of presenting and talking about our research in this way.

I had a number of anxieties about placing our research in this kind of space, not least the fear of someone angrily confronting me with the question of ‘What are you doing this for?’ or ‘What is the point of this?’. In a city that has been hit hard by the recession, might visitors feel angry about television history being given public funding (even minimal funding), might we be accused of ‘fabulous self indulgence’? In the press, radio and television interviews that I did leading up to the launch of the shop, I was repeatedly asked the same question: ‘What is the benefit of this research?’. Whilst I was able to answer that we felt, as a project team, that it was important, essential even, to document an element of television history about which little was known, and to take seriously women’s culture and women’s tastes and interests, picking up an argument that had been made around the first-wave of research into women’s television (namely the studies of soap opera initiated in the early Eighties), I felt trepidation about making these same arguments face to face with people in our ‘shop’.

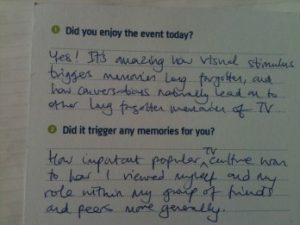

These fears were, however, entirely unfounded. What we found immediately was that people from all walks of life, and of all ages, were hugely enthusiastic about the exhibition on a number of fronts. Firstly, there were those who were pleased to simply see something other than a boarded up shop in the city centre: people felt it was an innovative use of neglected space and called for other similar exhibitions in our guest book. We also have been told repeatedly that it was nice to know ‘what people were up to up at the university’ – for example, an eighty six year old widow from Holbrooks in Coventry who talked at length about his ‘rationing’ of television viewing as opposed to his wife’s avid relationship with the soaps, commented in the visitor’s book as he left ‘A great idea, let the public know that UNI is NOT all beer and skittles. I hope it works well.’ However, the overwhelming response, repeatedly given in all forms of feedback, was how much people had enjoyed the opportunity to reminisce, and to be reminded of viewing long-forgotten, and for the ‘invitation to be nostalgic’. For example, a woman in her forties wrote the following:

Whilst another woman of the same age reflected on the ways in which the exhibition had prompted her to think about how television had fit into her family’s life:

What all of this suggests is that a great deal of value was placed on the invitation to nostalgia by the public visiting the Pop-up TV Pop Shop, and that my slightly tortured ‘What is it all for?’ worries about the subject of television history are not ones shared by the people of Coventry. For the people visiting the exhibition, confronted with ‘pop up history’ for the first time, the opportunity granted to talk about their memories by researchers interested in programmes and viewing practices familiar to them was both welcome and important. From our point of view it enabled us to talk to both men and women about programming that women identified as ‘theirs’; we found that many of the men we talked to also saw pop programming as significant in their ‘television history’, though usually in the context of acting as a precursor to ‘going out’ – we learned a lot of Coventry’s club scene in the 1960s. The women who visited the exhibition both confirmed the findings of our earlier audience research, that ‘their’ television was generically varied and that it intersected with their life histories in interesting ways, and also added to our growing lists of programmes and genres that women wanted to claim as being made for them.

In the era of the impact agenda, when others are doing fabulous work that speaks directly to, and makes an impact upon, the television industry (e.g. Cathy Johnson and Paul Grainge, James Bennett and Niki Strange), I hope that the ‘Pop-up TV Pop Shop’ might act as a catalyst for other research projects seeking to make an impact within their local communities, or with viewers, rather than producers of television. Indeed, what would be even more fabulous (but not fabulously indulgent, I hope) would be the opportunity to feed-back visitors’ nostalgic reminiscences, and their sometimes quite angry feelings about the loss of certain programme types and viewing practices (in this instance an ‘appointment to view’ regular, weekly pop programme) to broadcasters producing and scheduling television today. I probably won’t stop worrying about what television history is for, or about the role of nostalgia in the presentation of television history, but I’ve certainly gained an insight into public opinion of the kind of work that we do, in a very positive way.

Helen Wheatley on behalf of the ‘A History of Television for Women, 1947-89’ team: Hazel Collie, Mary Irwin, Rachel Moseley, Helen Wheatley, Helen Wood.

Helen Wheatley is Associate Professor in Film and Television Studies at the University of Warwick. She has published widely on popular genres in television drama in the UK and US (particularly the studio-based drama of the 1960s and 70s), and is the author of Gothic Television (MUP, 2006). She has an ongoing interest in issues of television history and historiography, and edited Re-viewing Television History: Critical Issues in Television Historiography (IB Tauris, 2007). Helen is currently writing a book on the notion of television spectacle and visual pleasure. She is co-investigator on the AHRC project A History of Television For Women in Britain, 1947-1989.