On July 18, 2015, Lena Dunham shared the following diagnosis for the title character from Daria (1997-2002), MTV’s cult animated series, with her two million Instagram followers:

‘I love Daria just as much as the next child of the 90s but I am also concerned not enough of us realized she was rude and almost definitely had clinical depression/could have benefitted from therapy and maybe some medication. I really don’t feel she, like, moved to New York and took the city by storm unless she got some help.’

Almost immediately, Dunham’s comments were called into question. As Jonno Revanche of Oyster magazine explains: ‘Daria is sassy and analytical – that doesn’t have to equate to being mentally ill. […] There’s not something wrong with you if you’re not accepting and cheery 24/7.’ Regardless of its validity – and ignoring the issue of how one can diagnose a fictional construct at all – Dunham’s diagnosis seems to reflect certain cultural expectations for how female characters (even animated ones) should behave, or risk being criticised as ’rude’ and in need of a mental reconfiguration.

The main reason Dunham’s diagnosis seems misguided is that the MTV series consistently foregrounded Daria’s personality, and the tendency for other characters to frame it pathologically as something that can and should be fixed. In the very first episode, Daria ‘fails’ a psychological exam and is sent to a self-esteem class. It’s here that she meets Jane, her like-minded sidekick for the duration of the show. Jane is taking the class, for the third time, since she has nothing better to do: she sees the class as a form of entertainment. Daria subsequently reassures her parents that she doesn’t have low self-esteem. She adds, with characteristic wit, that she instead has low esteem for everyone else.

Exchanges of this nature recur throughout the series. In addition to displaying resilience against outside attempts to modify her personality, Daria typically deflects such critiques by reminding us that she would much rather be the black sheep (of her family, school or society) than to be a part of the misguided herd. The show thus maintains that, while everyone treats Daria as though she is in need of saving, they are the ones who ultimately need help.

Not only does Daria acknowledge and endorse the title’s character’s ‘outsider’ status, but the producers use animation in unexpected ways to support Daria’s disaffectedness. In Prime Time Animation (ed. Stabile, 2013) Kathy M. Newman argues that Daria’s demeanour helped to show to become a ‘milestone in the evolution of animation’, as well as establishing Daria as an ironic and feminist heroine (187). Newman identifies an interesting tension between Daria being animated, technically speaking, and her lack of animation in terms of vocal range, expressions and gestures: ‘her perpetually half-closed eyes and monotone voice betrayed little emotion’ (187). For Newman, Daria thus serves as a meta-commentary on the medium of animation, further contributing to the show’s pervasive use of irony. Newman also praises Daria’s animators, who ‘used their artistic powers to create a young woman whose brain was more important than her bust’ (187), thus distinguishing Daria from the Jessica Rabbit school of physically seductive animated women.

Although the show’s initial run largely pre-dates digital media, characters’ reactions to Daria’s inexpressive face also anticipate recent discourse on women’s facial expressions and the language used to correct those deemed ‘inappropriate’. Firstly, Daria could be said to suffer from ‘resting bitch-face’, whereby a woman’s default facial expression is not obviously pleasant, leading others to assume she is a mean or angry woman; a so-called bitch. The term ‘resting bitch-face’ wasn’t circulating when Daria was on air: according to knowyourmeme.com and Google Trends the phrase first appeared in the summer of 2013. Yet given the rarity of Daria’s smiles and pleasing expressions, she, like Kristen Stewart, would be a prime target for the insult today. Instead, in an episode of the same name, Daria is labelled as ‘The Misery Chick’.

In a telling sequence Daria’s mother asks why she won’t smile, even for a school photo. Daria knowingly responds that ‘I don’t like to smile unless I have a reason’. Ignoring Daria’s justification, her concerned mother expands: ‘but people judge you by your expression’. Daria ‘wins’ the exchange, as she almost always does, with her deadpan response: ‘I believe there is something intrinsically wrong with that system, and I have dedicated myself to changing it’.

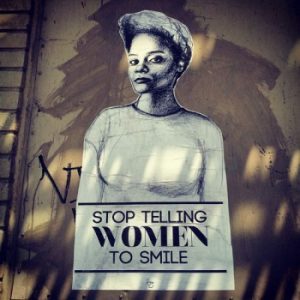

By having Daria defend her unwillingness to ‘put on’ a pleasant expression in order to put others at ease, the show foreshadows Tatyana Falalizadeh’s ‘Stop Telling Women To Smile’: since 2012, the traveling public art series has placed portraits of women on outdoor walls with a view to addressing gender-based street harassment. Frustrated by her personal experiences, Falalizadeh created a series of drawings which drew attention to the way that women’s expressions and bodies are publically monitored and critiqued.

For Dunham, Daria’s unwillingness to smile on demand (for a photographer, or anyone else) may come across as ‘rude’, yet, as Falalizadeh’s campaign underscores, the person at fault is the one requesting a smile, not the woman defending a very basic right to determine her own expressions. In other words, smiling infrequently should not be read as a sign that a woman – or, indeed, a character – is rude, a ‘bitch’, or a depressed ‘misery chick’.

Given that Dunham is often praised for addressing gendered body politics on her show, Girls (HBO, 2012—), it’s unfortunate that she pathologizes Daria’s unwillingness to people-please, and mistakes critical thinking and individuality for signs of an underlying disorder. Daria may have been rendered in a basic style of animation, but, as a character, she was three-dimensional and capable of taking the world by storm… without the help of medication.

Jennifer O’Meara is an Assistant Lecturer in Film Studies at Maynooth University, Ireland. Her recent publications include contributions on film music, performance and dialogue to The New Soundtrack, The Cine-files and Cinema Journal. She is currently researching participatory fandom in relation to unofficial film posters.