Right then – a new academic year. And that’s why I can see some new faces out there. Well, there’s a lot of questions that you’re going to be bombarded with as you make your way through Television Studies in the coming years. Questions like ‘Is That Argument Strong Enough?’, ‘Why Have You Missed All This Semester’s Seminars?’ and ‘What Do You Mean You’ve Never Heard Of VHS?’.

Oh, and I hope you like figs. There’s quite a lot of them to get through.

So, let’s start you off with an Easy question.

In the immortal words of Ted Rogers: 3… 2… 1…

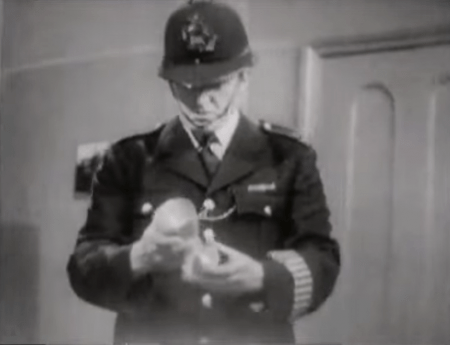

Fig. 1: “‘Alderman F Mayhew – From His Many Friends on the Dock Green Council’. The break-ins! You! You used your uniform, for this?”

Fig. 2: “Look Mr Dixon, I can explain that. I had to have money see. I did it the first time just as a lark. Nobody suspected a copper, see?”

Fig. 3: “Shut up! You can tell me all that at the station. There’s nothing worse than a rotten copper. Nothing! It’s the lowest thing that crawls on God’s earth. Take off that uniform. Take it off! And when you’ve got it off, put on something different. Then I’ll arrest you.”

Okay, so…

NAME THE ACTOR PLAYING THE BENT COPPER… [i]

WHO PLAYED GEORGE DIXON? [ii]

HOW DID HE GREET US EACH WEEK? [iii]

Did you get them right? I mean, surely, you can’t call yourself a student of television unless you got those right? That’s a pretty basic set of questions about the medium. And one that the Wells family were able to score maximum points on when they were posed by Noel Edmonds during an edition of BBC1’s quiz show Telly Addicts (1985-1998). They concerned The Rotten Apple, an episode of the BBC tv police procedural Dixon of Dock Green (1955-1976). The Rotten Apple had aired on 11 August 1956… and 31 years later, Noel was asking about it on 12 September 1987.

The arrival of television quiz shows about television – in the UK anyway – was one of the markers that the medium now had its own history and identity and was a thing worthy of celebration in its own right. An early example of this was Out of the Box (1972), a series of six themed nostalgia quizzes about different aspects of the history of BBC television presented by semi-apologetic comedy scripting legend Denis Norden as part of the Corporation’s Golden Jubilee. Without any formal allocation of points for the contestants, the exercise was less a competition recorded at BBC Manchester for BBC2 and more a cosy fireside ramble through some scrapbooks of yesteryear in the privacy of a parlour conducted – as it was – amongst those who made television for a living. The toughest question each week was likely: ‘Who on earth are those drawings in the opening credits meant to be, and are they there purely to avoid paying copyright on bona fide publicity shots?’

At this juncture, television was something that if to be shown to be understood at all on itself was to be shown to be understood by the people who made it – not the people who consumed it. When the North East ITV franchise Tyne Tees came up with the early afternoon game show Those Wonderful TV Times (1977-1978), the contestants were – again – television professionals. All consummate entertainers, but not necessarily the most engaging of contestants when quizzed about their own arena. After all, just because Kenneth Cope starred in ITC’s Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased) (1969-1970), should he be expected to recall the format of ITC’s Cannonball (1958-1959)? Singer and entertainer Joan Turner was a delightful contestant attempting to win money for her nominated charity, but her performance when it came to the questions led one to suspect that maybe she didn’t actually own a television.

Yet amidst this came the bursts of unexpected passion for The Box which were surprising and most endearing. 77-year-old comedian and actor Arthur Askey couldn’t answer fast enough in an edition recorded on 7 April 1978 when a clip from Episode 204 of the long-running Granada soap Coronation Street (1960-) – first aired on 26 November 1962 – was shown to the competitors. When host Norman Vaughan asked what had inspired Elsie Tanner and her friends to send out for fish and chips, Arthur keenly ventured “If my memory serves me right, Elsie’s daughter had come back from Canada.”

And he was right! And all of a sudden you thought: “Gosh! He doesn’t just sing songs about anthophila. He really loves his twice-weekly visits to Weatherfield! Just like I enjoy my Saturday teatime trips aboard the TARDIS!” You realised that there were stars in the business who really shared that interest and passion for the medium as fellow viewers.

But usually it was all pretty low-scoring stuff. And in case the celebs couldn’t immediately identify a clip from the memorable 1971 Play for Today (1970-1984) that dipped into the life of Edna, the Inebriate Woman, then a quick glance to the right of Norman Vaughan’s head would offer the prompt ‘EDNA, INNEBRIATE WOMAN’ painted on the backdrop below ‘THE FORSYTE SAGA’ (1967) and to the right of ‘ROUTE 66’ (1960-1964) – but, naturally, without the bracketed dates which are in that last clause only for reasons of academic convention – as replacement scenery for earlier illustrations which appeared to be the spiritual descendants of the opening captions to Out of the Box.

Barry Cryer – who had been Norman’s predecessor as the host of Those Wonderful TV Times – is somebody with a massive passion and knowledge for entertainment history, and this made him a perfect contestant for BBC1’s one-off So You Think You’re Switched On? Since 1965, the avuncular bumbling brilliance of Cliff Mitchelmore had encouraged viewers in their lounges to pit their wits against celebrities on his panel in a range of subjects from motoring through monetary matters to monarchs… and Uncle Cliff’s final topic of semi-educational interrogation on 4 January 1984 was to share the medium itself with the consumers.

Of course, while the viewers could take part, they couldn’t do so in front of the cameras – the closest they could get was the studio audience. Television hadn’t been a suitable subject to flaunt one’s knowledge – it was everyday life, like the price of milk or how to drive a car. It wasn’t specialist.

Not like film which was sort of specialist and worthy and involved you actually going out to a cinema if you were properly into it. Hence 1982 had seen BBC2 launch Film Buff of the Year (1982-1986) in which doctors from Wigan, accounts clerks from Derbyshire, careers officers from the Wirral or indeed anyone else could all flaunt their cinematic knowledge… only to be out-flaunted by deviser and host Robin Ray. Prior to this, Robin had been a regular fixture on BBC1’s The Movie Quiz (1972-1974), a more mainstream show on the parent channel where the public had been confined to their sofas or studio seats to watch Michael Aspel pitch the posers to the likes of Kate O’Mara or Harry H Corbett. Now on BBC2, the format was firmly placed in the hands of the true devotees. And it was pretty serious stuff.

“Is it those who watch it or those who appear in it?” was the question about who knew most about TV posed by Gloria Hunniford when she finally offered Joe and Josephine Public a chance to go head-to-head on screen with the celebs on We Love TV (1984-1986), a lightweight offering with jaunty theme tune [iv] made for LWT by B&E TV Productions. From September 1984, celebrity and civilian took their places at desks familiar from a million game shows at the “college of TV knowledge” which would offer tantalising glimpses of the opening titles to Public Eye (1965-1975) or maybe film of Patrick Macnee seated in a vintage Bentley asking about his time as Steed in The Avengers (1961-1969). Then, in a format tweak from 1985, one of the two small screen stars was now partnered off with one of the two amateur authorities. But Gloria remained the generous host, so good-natured that you still got the points if you said that Roy Hudd was Emu’s partner because he was “close enough” to Rod Hull.

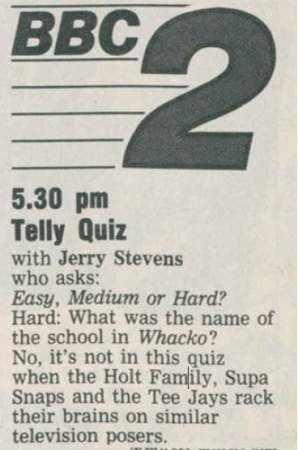

Doing away with the booking of expensive celebrities, the BBC got it right with Telly Quiz (1984-1985) from its Birmingham Pebble Mill Studios. Well, when I say ‘got it right’, clearly the BBC didn’t think so. My heart sang when I opened the Christmas double issue of the Radio Times in early December 1984 and discovered that across the festive fortnight, BBC2 was stripping my sort of quiz every afternoon on weekdays. But, oddly enough, before the closing theme tune – a delightfully frugal fanfare which was less BA Robertson and more ZX Spectrum – host Jerry Stevens would tell viewers at home “We hope you’ll join us again next week for Telly Quiz”… betraying that this had been destined for a prime-time early evening slot rather than being hidden away at Yuletide. Clearly somebody at BBC scheduling didn’t think that Pebble Mill had ‘got it right’.

Fig. 7: So… any ideas? [v]

In one important respect Telly Quiz did get it right. It got teams of viewers demonstrating their love and their knowledge, batting back answers to questions from behind their oh-so-formal panel game desks. Real people with real passion rather than the celebs who, one-booked, demonstrated all too often that they were too busy appearing on TV than watching it.

Jerry always offered the Telly Quiz teams a choice of three levels of questions: Easy, Medium or Hard. You’ve had your Easy – so, are you ready for a Medium yet?

You are? Good.

So… what did Pebble Mill do next which did work?

I’ll give you a few moments to confer.

We’ve mentioned it once already.

Sorry, I’ll have to hurry you…

Yes, that’s right. It was Telly Addicts (1985-1998). Probably the most effective vehicle developed to transform television into test. Taking the best elements of So You Think You’re Switched On? and offering an animated opening where the iconography was immediately recognisable, the everyday families were out from behind the desks and lecterns and placed in their natural habitat of the sofa, immediately recapturing that cosy parlour vibe from Out of the Box over a decade earlier.

Occasionally, television professionals were also allowed to play for seasonal specials… and one could marvel at the knowledge and enthusiasm for the subject from the likes of writer Barry Took or BBC1 controller Michael Grade. Okay, so, entertainer Larry Grayson did just sit there looking baffled but – after all – that was his act and you wouldn’t deny a professional their living would you? But, generally, it was real people. Including real people who demonstrated that televisual knowledge could be elevated to art form.

This was my kind of show. As you may be aware from previous postings, my undergraduate years were less Southern Comfort, sex and spliffs and more Southern’s scheduling of The Secret Service (1969). So, yes, with papers on Faraday’s law completed, I sat there keeping score alongside the legendary Pain family on queries about the likes of Burke’s Law (1963-1965).

But it wasn’t just an affirmation that my hours of viewing weren’t wasted.

I learnt stuff.

Decades before we could YouTube and before we could iPlay, shows like these forced open a crack in the doors of television archives and allowed the goodness to spill out as a smorgasbord of small screen specialities.

Telly Addicts came at just the right time. The notion of satellite and cable was only just taking off, the UK had a mere four channels, many homes still only had one TV set and long-running shows of earlier decades would repeat and repeat to fill the schedules. A family in 1987 could recognise enough elements of a programme from 1956 to play along because the catchphrases were engrained in society, the fledgling guest stars had gone onto primetime sitcoms, and George Dixon had still been on the Dock Green establishment as recently as 1976.

And in the 1980s, TV was acquiring its own history and nostalgia – that cosy 25 generational rule kicking in as parents shared their treasured childhood delights with their offspring. By the end of the decade, being an expert on your favourite TV show was almost an acceptable role in society – and one to capitalize on.

While Telly Addicts underwent format changes and even spawned the celeb-filled cousin Noel’s Telly Years (1996-1997), satellite channel UKGold – a home for archival programming established by companies such as the BBC and Thames – knew that their audience was precisely prime product for such shows. Zenith North’s Telly Stack (1996) came first in July 1996 – a glitzy affair where the budget allocated to the stack of tellies on the studio set meant that host Paul Ross and his three contestants had to react to a pre-recorded audience soundtrack during one viewer’s quest to go home with a golden television (wheeled on by that show’s guest). GoldMaster (1997) followed from January 1997 – a more refined offering from Thames which didn’t need to pretend that there was a studio audience as four experts in shows ranging form Hancock’s Half Hour (1956-1960) to Poldark (1975-1977) competed to keep their places in the knock-out tournament by answering questions from Mike Read. Every expense was spared… but that didn’t matter because the subject matter was strong.

And so it went on with diminishing returns as television decided that audiences wanted to see celebs and not themselves. Over at Auntie, Open Mike’s It’s Only TV But I Like It (1999-2002) with Jonathan Ross, BBC North West’s A Question of TV (2001) with Gaby Roslin and Shine’s As Seen on TV (2009) with Steve Jones all failed to reach the dizzy heights of Noel Edmonds in the days before he packaged Schrodinger’s Cat as a game show format. Shiver’s Show Me the Telly (2013) for ITV saw Richard Bacon evoking Gloria Hunniford in pitching TV Lovers against TV Legends, but lasted a single season, while on Channel 4 Charlie Brooker’s genuine passion for television helped the Zeppotron comedy quiz You Have Been Watching (2009-2010) to offer two seasons of rewarding celeb entertainment. In its backwater of nostalgia, UKTV Gold was home to items such as Classic Comeback (2006-2007) or The Sitcom Showdown (2006-2007) which did feature viewers. And the public were allowed to demonstrate their own skills on specialist – and usually cult – shows ranging from the Star Trek themed To Boldy Go Where No Quiz Has Gone Before (1996) through No 1 Soap Fan (2007) to Gameshow of Thrones (2019).

That’s all very well… but what show can I tune into for the infectious enthusiasm of a true television devotee? Something where the contestants wore their TV viewing hours with real pride… even maybe doing revision as the more serious claimants to the Telly Addicts title had done in its heyday?

Well – the most recent delight for me was Mastermind (1972-) or – more precisely – an edition of its spin-off Celebrity Mastermind (2002-). Back in December 2019 – when the world was a different place – I tuned in to watch the highly respected broadcaster and journalist Samira Ahmed whose work I admire on strands from Front Row (1998-) to Newswatch (2004-) answering questions on the 1970s SF film series Space: 1999 (1975-1977). Now, originally Mastermind was a bit of a stuffy old thing with its subject matter – and rightly so – for many years. At the outset it was Franz Liszt and Rudyard Kipling and harps and European mountaineering to 1914… with Hollywood grudgingly acknowledged by the end of its first decade but television not really featuring until the 1990s.

But as the lights go up on the contestants one by one, after illuminating three blokes sporting casual jackets, there’s a top BBC journalist clad in the beige glory of Rudi Gernreich’s Moonbase Alpha uniform – the yellow sleeve telling me that according to the Moonbase Alpha Technical Manual (Starlog: 1977) that Samira’s joined the ‘Data’ team of the castaway lunar establishment for the evening.

Seventies style showing as she approaches the famous black chair, Samira doesn’t just walk the walk, she talks the talk. She’s magnificent! She even knows that John Koenig took over from Commander Gorski – a character who appears in one episode for about 25 seconds. This isn’t just celeb exposure in the name of entertainment. The money won for her nominated charity [vi] when about 15 minutes later she is named Champion of Champions 2019 is an added bonus, but for me – somebody who also embarked on ATV’s space odyssey over forty years ago – it’s the fact that the self-proclaimed “nerdy girl at school who never won anything” has this opportunity for something from television so dear to her to be displayed in the same way that Big-Hearted Arthur’s eyes lit up in 1977 on seeing the Tanners of Salford.

Now, we’ve done Easy. You breezed Medium. So, here’s the Hard question.

How would you do a television-based quiz show as successful as Telly Addicts now?

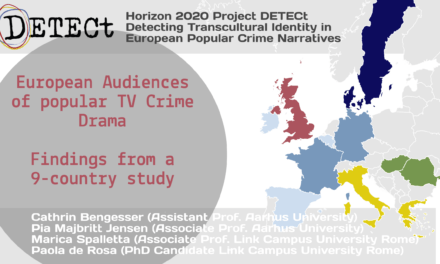

Denis Norden had little over 20 years of archival material to play with – we now have around 70. That tight focus of subject matter has dissipated. Tech means we’re no longer parochial with our own national identity. The big brands have to be global. Ich meine, hat irgendetwas von dem, was ich hier gesagt habe, einen Kontext für die Zuschauer in Deutschland? Продължаваш ли с мен там, в България? O è tutto questo “Il mio hovercraft è pieno di anguille?” per quanto ti riguarda?

Because ideally I’d like a first run of six ready for Week 1 2021 please with an option on a further thirteen for the autumn…

Andrew Pixley is a retired data developer. For the last 30 years he’s written about almost anything to do with television if people will pay him – and occasionally when they won’t. He’s met some very nice people who went on Telly Addicts, and they were utterly brilliant! And when he and his wife found the two Telly Addicts DVD games in CeX for 50p each last year, they were amazed how they could do the adult questions with no problem, but got very low scores on the kids’ questions. And that made them feel old…

Footnotes

[i] Paul Eddington

[ii] Jack Warner

[iii] ‘Evening All…’

[iv] ‘We Love TV!/No doubt about it!/Can’t live without it!/We Love TV!’

[v] It was Chislebury School.