I guess we have all had the experience of pointing a remote device at the wrong point of focus, and wondered why nothing was appearing on the screen. Or having sat on the TV remote accidentally, to create mayhem on the screen.

That might be the only times we have become more aware of our dependence on the remote. But the impact of such devices is much deeper and significantly more significant, according to Caetlin Benson-Allott’s recent publication Remote Control (2015). This investigation of the history, use and social impact of the remote control is another of the natty little Object Lessons series from Bloomsbury; short, palm-sized interrogations of everyday objects or practices such as Refrigerator, Golf Ball and Waste.

This history of the remote control begins with experiments in the 1890s, when remote switches were used to detonate even more explosive devices, such as the German FL-7 or fernlenboote (remote steering boat), which was designed to set off large loads of explosives via a fifty-mile long cable. Both Tesla and Marconi were involved in such early experiments.

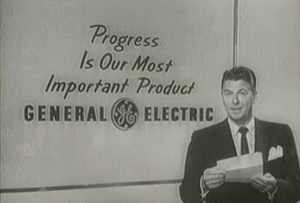

Remote controls devices, again tethered to lengthy wires, were developed in the early days of radio in America; often marketed as a status symbol for the household, as well as ‘taping into consumers’ desires for control over commercial media’ (25). The theme of ‘control’ is a recurring motif in Benson-Allott’s history, as she highlights the critical distinction between ‘control’ and ‘power’, as in the misleading claims made for early TV remotes (dating from Zenith’s ‘Lazy Bones’ device of 1950), and subsequent claims made about other electronic gadgets,

They helped convince us that remote control was the same thing as active engagement with the media. Remotes do offer many conveniences, but the “freedom” to sit back passively and choose is not the same thing as cultural intervention. (46)

We might describe this as distinguishing between having some control over content of television (channel surfing, for example) but having no control over the agenda (the inability to challenge the commercial imperatives of television).

Benson-Allott does not pay attention to another remote device, found in those homes of those individuals who comprise the panels for Peoplemeter measurement of television viewing. I think it would have been useful to have done so for such folk now constitute the official television audience in most countries, having a little more power than the rest of us, who have no say.

This is the only significant omission from this interesting little book (which can be read in a night), which adds weight to the argument that media shapes us in ways we seldom acknowledge nor discuss. It allows to focus on the economic and social impact of one seemingly innocent device, diverting our attention away from the screen for a brief moment as it activates other effects—from encouraging us to spend more time sitting down, to shaping new forms of patriarchal dominance of family spaces (males hogging the remote).

Geoff Lealand is Associate Professor in Screen and Media Studies, University of Waikato, New Zealand, where he teaches and writes about world cinema, television, children and media, and media education. You can check out his current research activities HERE. A yet to be fulfilled ambition is to watch all episodes of The Wire. He has been writing various pieces based on his research on Shirley Temple ‘double’ contests held in New Zealand in the 1930s; most recently including these investigations of cultural memory and fandom into his contribution on the child star in the Routledge Companion to Global Popular Culture, edited by fellow-cst contributor Toby Miller.