David came in, and what you had was long-form storytelling. Characters that were nuanced, stories that were nuanced, that required your attention and required you to follow it. Nothing was wrapped up at the end of one episode or one hour. It continued. It was sort of like a novel. I think it’s a visual novel – the way he looked at it.

People look at television, and you see the lead character, and you think that’s the protagonist. But I think, for David the protagonist is actually America. American society is always the protagonist.

– Michael Potts, The Wire and Show Me a Hero (Halskov & Sørensen 2019)

We all know the story: An external force is threatening to eliminate the world and disturb the social order, as we know it. A strong man is put on the case and uses his will and agency to overcome the external threat and his inner conflict before restoring order and our collective faith in society and humankind. The typical Hollywood film follows a fairly well-known formula. It has a clear and well-defined plot, follows a straight corridor and takes few excursions on the way toward the happy ending at the end of the corridor. It has a strong protagonist at the center of the story – a character who is promptly introduced and who sets the plot in motion, which then unfolds as a neat series of causes and effects. This principle of individualized causality is seen in most Hollywood films, and many of these principles are also apparent in the serialized fiction that we see in American television (cf. Bordwell 1986 and Nielsen 2013).

These characteristics, however, are not typical of the fictional stories by TV creator and showrunner David Simon, who began his career as a journalist and who helped define the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of cable television at the turn of the century. Through lauded TV classics like Homicide: Life on the Street (NBC, 1993-1999; Fig. 1), The Corner (HBO, 2000), The Wire (HBO, 2002-2008), Generation Kill (HBO, 2008), Treme (HBO, 2010-2013) and The Deuce (HBO, 2017-), Simon has come to define a pivotal shift in American television, largely by going against the grain of American politics and traditional formulas known from Hollywood and American television.

If the classical Hollywood film deals with strong individuals who prevail and restore the social order, then Simon’s fictions are often about structural issues and institutions that fail. And while a classical Hollywood film has one clear protagonist with a clearly defined goal, then Simon’s stories are more anthropological and ambiguous in nature, without a clear center and an evident telos.

Fig. 1: Homicide: Life on the Street (NBC, 1993-1999) – one of the most significant TV series of the 1990s that helped pave the way for the Golden Age of American television drama at the turn of the century. The Golden Age would largely become a cable phenomenon, connected to premium cable networks like HBO and showrunners like David Simon. © NBC.

David Simon is a powerful voice in the political debate, a crucial flagship for HBO and one of the most central and critically acclaimed TV auteurs in the modern mediascape (cf. Nørgaard 2011). He has some strong and unflinching views on American society and the American TV landscape, and he has his very own modus operandi. Therefore, I have spoken with Simon about his particular approach to storytelling – his use of the past, his sociological or journalistic method and his stylistic and narrative choices – and about the intersections between his works, the political climate and the modern TV landscape. And his conclusion is clear as a bell: When American television got rid of the advertisers, serialized television matured, and serialized, long-form storytelling and modern cable networks are the crucial pillars of Simon’s sociological stories.

From Attraction to Allegory: (Ab)using the Past

When browsing the modern TV and streaming landscape, it is impossible not to notice the many popular shows that utilize or deal with the past. Period drama is in vogue, it seems, in the form of nostalgic flashbacks to a simpler time (cf. Stranger Things [Netflix, 2016-] and Everything Sucks! [Netflix, 2018]), aesthetic refashionings of the past (cf. Mad Men, AMC, 2007-2015) or more allegorical stories that use the past to comment on the present (cf. The Americans [FX, 2013-2018] and Chernobyl [HBO/Sky Atlantic, 2019]). David Simon also utilizes the past, when he deals with the political climate and the housing problems of Yonkers in the 1980s (Show Me a Hero) or when he depicts exploitation and sex work in New York in the 1970s (The Deuce). In Simon’s works, however, the past is not just an attraction or a setting, and the tone is never nostalgic and revisionist.

This is illustrated, for example, in the end of The Deuce which produces a shocking parallelism between New York in 1970s and modern-day America, neatly showing the things that have changed in the course of the last 40 years and the many things that have not – and never will – change. Behind the immediate sense of historical development there is a deeper and more urgent sense of stagnancy and repetition: “The more things change, the more they stay the same.

AH: I know that you are working on two different shows at the moment, and both of them are essentially period dramas. Could you tell us about the miniseries that you are editing as we speak?

DS: The story is based on a novel by Philip Roth called The Plot Against America. It is an alternative history of America, based around the election of 1940 that was premised on the idea that instead of Franklin Roosevelt being elected on the dawn of World War II, America elected an isolationist Republican in the form of Charles Lindbergh, the aviator, who historically was, in fact, pro Nazis and also violently anti-Semitic as well. And, so, he brings America in on the side of strict neutrality while, at the same time, supporting Hitler. It was an artefact when it was published in 2004. Roth was writing with the election of George W. Bush in mind and some degree of populism as being a rallying point for American politics. Obviously, in the wake of the election of Donald Trump, it has gotten a greater significance, so we optioned the book, and HBO is making it into a miniseries that will be out in March next year.

AH: Like The Deuce and Show Me a Hero, your forthcoming miniseries looks to the past in order to speak about the current political climate. Sometimes, period dramas seem like nostalgic glances into the past, which is often aestheticized or romanticized, but you seem to use the past as a sort of mirror. Is that the idea?

DS: Absolutely. There’s no point in doing period drama, if you’re not reflecting on the world that currently exists. The problems of a hyper-segregated society and inequality are even more profound today than they were at the time of Show Me a Hero. The same things are going on in every city about what to do with the poor, where to put the poor. At this moment, there’ll be 67,000 people in the homeless shelters in New York City, which is an all-time record in one of the most affluent cities in the world. That is, in fact, the case. There’s a dearth of affordable housing. The city is a playground for the rich and hell for the poor. So there is nothing being said about Yonkers in the 1980s in Show Me a Hero that can’t be applied now to our current society.

Similarly, The Deuce is about misogyny, sexual commodification and labor and gender, and those topics are still relevant. The status of women in society is being questioned as aggressively today with #metoo and #timesup as it ever has been. The same arguments are still unresolved. So, if you’re not speaking of the present, you’ve got no business accessing the past.

”The centre cannot hold”: The Structural Focus

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

– W.B. Yeats, “The Second Coming” (1919)

Before Show Me a Hero and The Deuce, David Simon created one of the most significant and popular TV series of the 2000s – a piece which is often placed at the tops when critics and reviewers are asked to list the best TV shows of all time. I am naturally referring to The Wire, which differed markedly from other quality shows of its time by focusing on environment rather than plot, structures rather than strong individuals, and by changing the setting and the focal points with each season. The Norwegian TV scholar Erlend Lavik points to The Wire as the most paradigmatic example of quality TV and the most crucial work in the so-called Third Golden Age of American television drama. The Wire is also mentioned by Alan Sepinwall and Matt Zoller Seitz as one of the all-time greatest American TV series, and they, fittingly, use a string of questions when trying to summarize the plot in all of its complexity:

The Wire is about a clever cop who doesn’t play by his bosses’ rules.

Or is it about how that cop pushes his bosses to create a task force to take down a dangerous inner-city drug crew?

Maybe it’s about the charismatic leaders of that drug crew?

Could it be about dysfunction inside the police department?

Wait… now it’s about the stevedores’ union?

Only now the mayoral campaign is the most important thing?

How is the show suddenly about four boys in middle school?

And here at the end it’s about the inner workings of the city’s biggest newspaper?

What on earth is the show supposed to be about, people?

(Sepinwall & Seitz 2016: 37)

AH: What’s interesting about The Wire, as I see it, is that it explores the problematic structures and failed institutions in the USA, instead of focusing on strong individuals and immediately exciting plots. It was a groundbreaking show, and it has been described as neo-realism, sociology, anthropology, a systemic critique of America and many other things. How do you see it?

DS: It’s a critique of why we can’t solve any of our problems nationally. There are problems that have to do with how we live together, and how we live together in the 21st century is inevitably an urban question. Urbanity is now the future of humankind, and the shape and structure and viability of the city is going to determine whether or not we survive as a species. In that sense, we’re using the city allegorically to make arguments about what has gone wrong with our society that our institutions no longer perform or even attempt to perform as they once did and how problems and even the attempts to solve problems become more and more elusive – and why the center of our society, which used to be some communal sense of responsibility, can no longer hold.

So, yeah, listen, I have no interest in telling stories about characters. Characters are building blocks, and you have to write interesting characters, and you have to care about your characters as a writer, but characters are basically a tool in the tool box to tell a story about something larger. At least it is in our construct of what we’re doing, and that’s true not just for The Wire, but for all of our pieces. Every single one. We’ve done seven pieces now for HBO, and we’re about to cut together an eighth, and they’re all about structure. They’re all about the systemic. And that has to prevail for us to care about it.

And one of the reasons we found that to be a plausible pursuit is that we’re doing long-form. We’re doing long-form television shows. We’re doing miniseries and series, so there’s time to lay out the structural critique. There’s no time to do that in a two-hour movie. It’s an improbable thing to do in two-hour movie. Around a small structure, you can do something specific about a problem in a certain institution, maybe, in two hours, but you’re not going to be able to critique the larger constructs of society in an hour and a half, two hours or even two and a half hours. For that, you are going to need six, 12 or 20 hours, depending on what you’re talking about.

AH: Indeed. Many people have pointed to The Wire as central to the so-called Golden Age of cable television. What precipitated that shift in American television?

DS: American television was a juvenile form in fundamental ways, until there were some channels that could get rid of advertising and commercials as the revenue stream. When they were the revenue stream, you could not present a story that was particularly dark or disturbing or problematic or argumentative in a political sense because it disturbed the consumer class. It disturbed the dynamic between the advertiser and the consumer. It didn’t put anyone in the mood to buy cars or blue jeans or iPods or anything. But once you got rid of the advertisers and made it a subscription model, now you started having grown-up stories.

Fig. 2: David Simon at the 63rd Annual Peabody Award with two actors from The Wire: Lawrence Gilliard, Jr. (left) and Dominic West (right). Photo: Anders Krusberg / Peabody Awards, 63rd Annual Peabody Awards Luncheon, Waldorf Astoria Hotel, May 17, 2004. Creative Commons.

AH: Many people have also pointed to the level of attention and patience that a show like The Wire requires. I guess we could say the same thing about Treme (a show about the effects of Hurricane Katrina as both a natural and social disaster), which had such an interesting opening, almost reminiscent of Italian Neo-Realism, and such a jazzy, slow-paced style.

DS: I’m particularly proud of that one, actually, in that it avoids, it denies itself, all of the tropes and metrics by which American television usually measures itself. It only has enough violence to depict the actuality of violence in the city. It only has enough sexuality to accurately chronicle the lives of ordinary people. It’s not trading on the things that make television shows go forward. It’s a lot harder to get people to watch a show where you put a trombone in a guy’s hand, than if you put a gun or a blonde, and we were determined to say something, again, about the American city. What in urbanity matters? What is resilient? What must endure? Treme is a show about culture. It’s about the culture of a city that’s steeped in culture, and it survives only because of culture. It was an attempt to make an argument for the city.

There were a lot of people who watched The Wire and said, “Man, why don’t they leave?”, which I thought was an astonishing reply to what The Wire was presenting. Nobody’s going anywhere. Baltimore’s going to be there tomorrow. The question is what it will be and whether or not we have the national stamina to address our problems. So I was a little bit distressed to find that people thought Baltimore was in any way aberrant or was enduring more than many other American cities like it. Baltimore is no different than St. Louis, Cleveland or New Orleans. In fact, there are only three cities in America that have any reprieve from these forces that are arrayed against them, and that’s New York, Los Angeles and Washington. And the reasons are obvious. New York is the financial capital of the world, and so the run-up on Wall Street eventually trickles down and allows them to rebuild the city and an incredible revenue stream. Los Angeles, at least the west side of Los Angeles, is floated by the American entertainment industry which is recession-proof. And Washington, being the federal city, which survives on the largesse of the government itself, is also recession-proof. Everything else in America has to fight. We have to fight the poverty of our politics and the poverty of our spirit, and we have to fight bombs of national contempt for the idea of the city, which is self-defeating.

Creative Treatments of Actuality

The Scottish filmmaker John Grierson famously defined documentary as “the creative treatment of actuality”, and this definition has since been echoed whenever dealing with documentary films or reality-based fictions. David Simon creates serialized fiction and is hardly a documentarist, yet his pieces reflect reality – current events or historical facts – and are often based on meticulous, journalistic research. I asked Simon about his anthropological or sociological approach and the fact that he still lives in Baltimore and goes out into the field when making TV series, in order to depict reality with a high degree of authenticity and an almost Griersonian ethos.

AH: I know that you still live in Baltimore, and I was wondering whether your projects would even be possible if you lived in LA – far removed, both geographically and conceptually, from the places that you explore and depict in your shows?

DS: Listen, the last three projects I’ve done have been in the New York and New Jersey area, and I’m from Baltimore, so the trick is to do as much research as you can, spend as much time on the ground as you can, so your view is clarified, hire other writers, researchers and experts who know the material and know the geography – which we did in New Orleans and which we did, when it came to the Marine Corps in Generation Kill, and which we did in New York. Do the work. That’s it. You’re obliged to do the work. There’s nothing to say that someone from LA can’t write a good and precise piece about Baltimore, but they have to go there. They have to meet people, they have to do the research, and they have to deliver. If they’re just going to sit where they are and guess from what they know in LA – or, even worse, West LA – then you can imagine how it’s going to turn out.

From Neo-Realism to #metoo: Topical Issues and Universal Stories

At the end of the 1940s, an artistic movement was born in Italy – a movement that, however short-lived, would come to change the face of Italian cinema and influence numerous waves in the international history of film. I am referring, here, to Italian Neo-Realism, a movement that rebelled against the lighthearted and reactionary telephone films of the time (telefoni bianchi) and the opulent dramas known from Hollywood which were often set in exotic locations, in other eras or glorious ‘otherworlds’. The Neo-Realists wanted to tell stories about “the pressing issues of the time” (Zavattini 1965: 11-13) without the make-up and artifice of Hollywood and the Fascist undertones of Italian films in the 1930s and early ‘40s. They used location shooting, dialects, open-ended plots and amateur actors, and their films dealt with real problems for workers and other regular people. Not the fancy Hollywood divas on the film posters, but the guy who rides around on his bicycle, putting up those posters to make ends meet (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: The poor protagonist in Vittorio De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette (1948, Bicycle Thieves) puts up posters of fancy Hollywood divas like Rita Hayworth – as an ironic contrast to his own working-class existence. While situated in America, David Simon’s TV series have a lot in common with the Italian Neo-Realist films from the 1940s, both thematically and tonally. © Image Entertainment.

David Simon’s TV series resonate with this movement, and the use of location shooting and the collective focus on working-class characters in pieces like The Wire and Treme have a lot in common with the films of Vittorio De Sica, Luchino Visconti and Roberto Rossellini. I asked David Simon about this potential source of inspiration and what he thinks about the Neo-Realist ideas, as mentioned by the script writer Cesare Zavattini.

AH: I have always seen your TV series as a serialized and modernized version of Italian Neo-Realism – a movement which was recognized for its use of location shooting, open-ended and decentralized stories, and amateurs who speak in dialect and the vernacular. The ideas behind the Neo-Realist movement were formulated by the writer Cesare Zavattini, who claimed that all good movies depict “the pressing issues of their time”. To me, that line could almost be a dictum of your work. Would you agree with Zavattini, or is it a far-fetched comparison to begin with?

DS: I would not be so limiting. I would say that’s what my work has to be because my training is in journalism, not in film and certainly not in the entertainment industry. So what I’m chasing has some rooted logic in journalism, and journalism is about the issues of our time. From my point of view, this is all I know how to do, but I can certainly conceive of great art that targets not simply the social issues of our time, but maybe just the human condition in general. Or maybe I’m speaking in such generalities that those are always issues of our time. Shakespeare works and the Greek plays work because man is man and his nature is his nature, and the forms by which power and dignity ground themselves, through humanity or through the human condition, don’t really ever change. The scale of hope and risk for human beings is the same for Hamlet as it is for Oedipus. This stuff works because we can watch Medea and we can encounter her trauma through our own knowledge of domestic pain and gender. And it’s not really of our time, it’s of every time. I don’t know, sometimes a good story is just a good story, right? I don’t want to get in the way of a good story by saying it’s all going to be rooted in contemporary politics, but I know there are things I can’t do, and what I can do is rooted in where I came from, which is journalism.

AH: The Deuce certainly seems topical too, and it seems to address many of the issues concerning gender, sex and sexuality that have been debated in the media the last couple of years. Do you think that movements or waves like #metoo and #timesup will actually change the media landscape?

DS: In the entertainment industry, I’ve seen the demeanor of people change, and largely for the better. Structurally, on set. Even on The Deuce we’ve improved the means by which we depict sexuality. We started to contemplate and emphasize certain structural changes in terms of how we shoot simulated sex, which is a big deal for performers. And I think the demeanor of how people respond to subordinates and how you behave in the office – I think people have taken pause, and it’s a good thing. And, I think, certainly you want the most egregious cases to be the paradigm examples of reform. I mean, Les Moonves, Bill Cosby and Harvey Weinstein are fundamental, and there’s a reason they stand out. They should stand out.

To give one note of caution, which I think is fair to say: If we’re going to replace The Court of Law and a determination of who is a sexual predator with judgment of employers and corporations as to whether or not someone can be employed or not employed, then that requires a certain amount of nuance, clarity and attention to detail. In the initial stages of #metoo and #timesup, all of the targets did seem to be those who were operating at great extremity and those who were actually being sexual predators.

I had an experience on The Deuce where one of our actors, Mr. Franco, was critiqued – there was a piece in one of the newspapers about problems he had had making independent films and teaching film courses – and there came a moment where we had to look at it very seriously. Obviously, because of what the show is about it was even more important for us. We looked at it with great care, case by case, detail by detail. And what we found was – while there certainly may have been mistakes made with people’s level of comfort on a film set, and there may have been mistakes made with Mr. Franco himself being a little bit oblivious to his own power to convince people or to get people to do what they would later on regret in terms of nudity (I don’t think he was aware of his own James Franconess, to be honest with you; in some fundamental way, he underestimated just what it means when James Franco is going to teach you a course or put you in a small indie movie) – but what was missing from all those critiques, which was obvious to the Weinstein, Cosby, Moonves cohort, was that James Franco wasn’t trying to sleep with anybody. He wasn’t trying to trade his power. He never asked for sexual favors. Obviously things went wrong, and people were unhappy – I don’t mean to dismiss that unhappiness; that’s a cause for looking at it and a cause for reform – but I was faced with working with someone who genuinely had not tried to use his position to achieve any sexual favor with anyone. He hadn’t asked anybody, and nobody was accusing him of that, so I got to the point – we were confronted with a lot of calls to exile James Franco from the production – where none of us at HBO could find the justification to do that. That would have been an inappropriate level of response. That’s not to suggest that what was critiqued isn’t deserving of critique or that James should not respond to that, but to have him in the same category as Weinstein or Moonves is an affront to the facts, and it actually diminishes the value and the purpose of #metoo.

When you flatten all offense and all error and make everything the same thing, you’re not helping the cause. You’re, in fact, making what is a substantial critique of sexual predation less substantial. So, if you’re asking about the movement, I support this thing. I support this thing, and I understand that it actually has the capacity to change things within the industry. But, on the other hand, its initial application has been rather a blunt weapon, and I don’t know how we fix that. It’s not like there’s a Board of Review. It’s a very informal thing that happens which is, basically, it hits the newspapers and we all contemplate it. But it’s not like there’s some governing body which you can appeal to and there’s a ruling as to what is sexual predation and what is mere error.

We made errors. In the first season of filming The Deuce, we made errors in terms of contributing to people’s discomfort at times, and we certainly weren’t trying to do it because we knew what we were chasing and how hard it was to film it. But we got better as we went.

So that would be my only critique: As we go on with this thing, I think everybody has to get smarter about what is x and what is y.

AH: One of the things that many cable shows have utilized as something of an attraction is, in fact, nudity and sex. I think The Deuce manages to avoid exploitation, but how do you toe the line between depicting sex and exploitation without becoming potentially exploitative yourself?

DS: We thought about every frame of film on this show because we understand that if you create porn to critique porn, there’s a latent hypocrisy that the piece can’t overcome. So we were very conscious about every frame: How long the camera stays, what the camera sees, why the camera sees it. These discussions were had on every episode.

AH: And Maggie Gyllenhaal is just wonderful in it…

DS: I’ll tell you this: The cast is so deep that, as wonderful as Maggie is, I wish more people would also credit Emily Meade and Margarita Levieva ‘cause they’re all delivering. I just wish there was more oxygen for everybody.

AH: I see your point. I’ve always loved Michael Potts’ character in The Wire, for example, even if it isn’t one of the most prominent characters.

DS: There’s only so much oxygen, sadly.

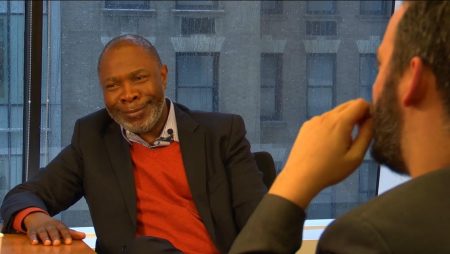

Fig. 4: Michael Potts from The Wire and Show Me a Hero argues that David Simon changed the face of TV by creating long, complex stories about American society and failing institutions. Photo: Jan Oxholm, New York, 2019.

Epilogue: From Cable-Revolution to Multiplatform Television

In 1991 David Simon wrote a journalistic book entitled Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, depicting a police department in the crime-ridden area of Baltimore, and the TV adaptation of that book, Homicide: Life on the Street (NBC, 1993-1999), would help pave the way for the Golden Age of American television at the end of the 1990s.

The TV landscape would not change dramatically, though, until the advent of the major cable networks and their introduction of original programming at the turn of the century. HBO is often seen as the central game-changer in this context, and its slogan, “It’s not TV. It’s HBO”, became a sort of motto for the general changes in the TV landscape and an illustration of the “not-TV” branding of the cable networks (whether premium cable or basic cable). HBO promoted itself as something more than traditional television, and their prestigious drama series are often seen as something else, entirely, than conventional TV serials. There has even been talk of an “HBO Playbook” which the other cable networks and major broadcasters hoped to emulate: a set of stylistic and narrative principles that HBO had almost been able to claim as their own. These included transgressive content, social critique, narrative complexity, morally ambiguous characters and antiheroes, large ensembles, niche-marketing, narrowcasting and an increased focus on TV auteurs with strong names and recognizable trademarks (cf. Højere & Halskov 2011).

This is a well-known story by now, and many books have been written on the tradition of quality in American television (Akass & McCabe 2007), also known as The Third Golden Age (Nielsen et al. 2011), Peak TV (Halskov 2015) or even The Platinum Age of Television (Bianculli 2016). The importance of HBO in this context is also well-documented, and the TV scholars Kim Akass and Janet McCabe summarize HBO’s history and importance in the following way:

Across its history HBO has repeatedly pushed the boundaries of the medium – in terms of delivery, form and content – motivated by its economically precarious and, at times, institutionally marginal position in the US audiovisual media ecology. HBO started as a small enterprise situated on the very fringes of the US TV industry. Without much media fanfare HBO launched on 8 November 1972, with the 1971 film, Sometimes a Great Notion (dir. Paul Newman, 1970) starring Paul Newman and Henry Fonda, followed by a NHL hockey game between the New York Rangers and the Vancouver Canuck. Three hundred and sixty-five Service Electric subscribers in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania were the first to receive HBO (DeFino 2014). As of December 2013 HBO had an established 43 million domestic subscribers and by 2015 that figure had risen to 49 million, which included users of its newly launched streaming service, HBO NOW (Statista). HBO has gone from a small, almost regional service in the northeastern and Mid-Atlantic area of the United States to become a truly global brand and an internationally networked owner-syndicator.

(Akass & McCabe 2018)

Akass and McCabe point to HBO as a sort of ’first-mover’, and they write about HBO’s ability to brand their content as particularly ”prestigious” and ”exclusive”. In this context, the TV auteur or showrunner plays a vital role, and David Simon has become an important flagship for HBO, creating many of their most prestigious drama series (TV critics talk about flagship shows, high-end television and Quality TV, whereas David Simon describes his own TV series as ”teleplays” or ”pieces”, echoing the quality series of the 1940s and ‘50s).

Much has been said and written about this change or paradigm shift in the TV landscape, and many critics agree on Simon’s importance to this shift and the modern TV series (cf. Gjelsvik & Bruhn 2011, Lavik 2014 and Nochimson 2019).

A lot has happened, though, since the premieres of Homicide and The Wire, and we could possibly talk of a new paradigm shift in the American (and global) mediascape during the last decade. Trishia Dunleavy (2018) writes about a shift from cable-revolution to multiplatform television, Neil Landau talks about TV outside the box (2016), and Martha Nochimson (2019) argues that the TV industry and the TV series have been rewired.

The modern TV series is seen on many different platforms and in various contexts, and phenomena like Video on Demand (VOD), DVD- and Blu-ray-boxes (HBO were also pioneers in that area), smartphones, tablets and cord-cutting have all contributed to some major shifts in the mediascape and have all but changed our understanding of the word ”TV series”. According to Akass and McCabe: ”the TV viewer has been remade within these technologies and the new technologies have […] allowed for new ways of consuming, watching and appreciating television” (Akass & McCabe 2018).

In the modern streaming landscape, the competition between different outlets, platforms and producers is bigger, and companies and conglomerates like Comcast, Apple, Disney and Netflix have moved the tent poles and challenged the status of cable networks like HBO. The question is where this leaves HBO, their focus on ”prestige”, ”exclusivity” and TV auteurs like David Simon.

With AT&T’s take-over, it looks as if HBO is changing and approaching the model of Netflix. HBO are still supposed to create award-winning drama series, but, according to AT&T’s John Stankey, they are also supposed to produce more content, hoping to survive the competition from players like Netflix and Hulu (cf. Alexander 2019). The new streaming service, HBO Max, will include many of HBO’s prestigious shows but also a broader selections of shows from different channels and producers. Variety describes this change as a jump from ”boutique” to ”big box”, and this could have major consequences for HBO as a brand. Can HBO produce a bigger output and let their prestigious TV series be part of broader bulks of entertainment and still maintain their strong brand as a producer of exclusive and alternative content?

Where this leaves HBO and the showrunner David Simon, is unclear. But even if Simon deals with the past – the 1980s in Show Me a Hero, the 1970s in The Deuce and the 1940s in the forthcoming The Plot Against America – it would be unfair to label him and his shows as relics of the past. Simon was a central flagship for HBO, when they revolutionized the TV-landscape in the beginning of the 2000s, and he will probably be a crucial part of HBO as they try to compete and position themselves in the modern and highly competitive streaming landscape.

In any case, we will always need authentic and socially relevant stories that utilize the past to speak to the present, and there will always be a demand for personal TV creators and strong, influential voices. Someone like Simon.

Andreas Halskov (b. 1981) holds an MA in Film Studies from Copenhagen University. Halskov is a lecturer in Media Studies at Aarhus University, and he works as a film/TV expert in different media and as a curator of film historical screenings at Cinemateket in Copenhagen and Øst for Paradis in Aarhus, besides being an editor of the scholarly film journal 16:9. Halskov has published numerous articles in journals like Kosmorama, Series, Short Film Studies, International Journal of Digital Television and Blue Rose Magazine, and he has co-written and edited four Danish anthologies on American television (Fjernsyn for viderekomne, Turbine, 2011), the Oscars (Guldfeber, Turbine, 2013), audiovisual comedy (Helt til grin, VIA Film & Transmedia, 2016) and tendencies in the modern streaming landscape (Streaming for viderekomne, VIA Film & Transmedia, 2019) Finally, he has written a monograph on David Lynch, co-written a book about vampire films and series and written two peer-reviewed books about modern TV drama (TV Peaks: Twin Peaks and Modern Television Drama, University Press of Southern Denmark, 2015) and serialization (Remakes, sequels og serialisering, Samfundslitteratur, 2019). An English book about David Lynch will be published in 2018/2019, as will an interview-based book about sound design in film and television, and he has contributed to a British anthology on Global TV Horror (eds. Lorna Jowett & Stacey Abbott, University of Wales Pres). Finally, he has co-created a five-part documentary series about the American TV landscape (Serierejser/TV Travels, VES/HBO Nordic, 2019).

Notes and Literature

Note: This interview was conducted for a small documentary project (Serierejser/TV Travels, VES/HBO Nordic, 2019) and is featured in full on 16:9 and in the edited collection Streaming for viderekomne (eds. Henrik Højer et al., VIA Film & Transmedia, 2019; in Danish).

Akass, Kim & Janet McCabe (2007): Quality TV: Contemporary American Television and Beyond. London: I.B. Tauris.

Akass, Kim & Janet McCabe (2018): “HBO and the Aristocracy of Contemporary TV Culture: affiliations and legitimatising television culture, post-2007”, Mise au point, 10 | 2018, January 15, 2018. Online : http://journals.openedition.org/map/2472 ; DOI : 10.4000/map.2472

Alexander, Julia (2019): “Can HBO Now survive HBO Max”, The Verge, September 27. Online: https://theverge.com/2019/9/27/20881734/hbo-now-max-streaming-wars-friends-big-bang-theory-warnermedia-netflix-disney-apple

Bianculli, David (2016): The Platinum Age of Television: From I Love Lucy to The Walking Dead, How TV Became Terrific. New York: Doubleday.

Bordwell, David (1986): “Classical Hollywood Cinema: Narrational Principles and Procedures”, Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology, ed. Philip Rosen. New York: Columbia University Press.

Dunleavy, Trishia (2018): Complex Serial Drama and Multiplatform Television. New York & London: Routledge.

Gjelsvik, Anne & Jørgen Bruhn (2011): “Listen carefully – The Wires opgør med politiserien”, Fjernsyn for viderekomne, eds. Jakob Isak Nielsen et al. Aarhus: Turbine: 115-129.

Halskov, Andreas (2015): TV Peaks: Twin Peaks and Modern Television Drama. Odense: University Press of Southern Denmark.

Halskov, Andreas & Kim Sørensen (2019): “Interview with Michael Potts”, Serierejser/TV Travels (VES/HBO Nordic, 2019)

Højer, Henrik & Andreas Halskov (2011): ”Kunsten ligger i nichen: ’The HBO Playbook’”, Kosmorama #248, Winter 2011. Online: http://video.dfi.dk/Kosmorama/magasiner/248/kosmorama248_037_artikel2.pdf

Lavik, Erlend (2014): Tv-serier: The Wire og den tredje gullalderen. Universitetsforlaget.

Landau, Neil (2016): TV Outside the Box: Trailblazing in the Digital Television Revolution. New York & London: Focal Press.

Nielsen, Jakob Isak et al. (2011): Fjernsyn for viderekomne – de nye amerikanske tv-serier. Aarhus: Turbine.

Nielsen, Jakob Isak (2013): ”The Oscars og den klassiske Hollywoodfilm”, Guldfeber – på sporet af Oscarfilmen, eds. Henrik Højer et al. Aarhus: Turbine.

Nochimson, Martha (2019): Television Rewired: The Rise of the Auteur Series. Austin: The University of Texas Press.

Nørgaard, Thomas (2011): ”Tv-auteurs”, 16:9 #40. Online: http://www.16-9.dk/2011-02/side06_feature3.htm

Sepinwall, Alan & Matt Zoller Seitz (2016): TV (The Book): Two Experts Pick the Greatest American Shows of All Time. New York & Boston: Grand Central Publishing.

Wallenstein, Andrew (2018): “AT&T Getting ‘Tough’ on HBO? More Like Tough Love”, Variety, 10. juli. Online: https://variety.com/2018/digital/opinion/att-getting-tough-on-hbo-more-like-tough-love-1202869343/

Yeats, W.B. (1921 [1919): ”The Second Coming”, in Michael Robarts and the Dancer, Everyman’s Library Pocket Poets, publ. David Campbell.

Zavattini, Cesare (1965): ”Nogle idéer om filmkunsten”, in Se – det er film, eds. Ib Monty & Morten Piil 1965: 11-13.