The media’s power to imbue particular places with the authority to be sites of interesting and pertinent stories fascinates me. It also feels like it is a process in operation everywhere. This summer, an article in The Times caught my eye because it was titled, ‘Thank goodness Edinburgh hasn’t gone all Scottish’. It’s a classic bit of journalistic word-play, but for the life of me I couldn’t grasp why Edinburgh should disavow its Scottishness. The article was by Neil Fisher, deputy arts editor, and it lamented debates in Scotland that the Edinburgh festival really could benefit from having a bit more of a Scottish flavour as advocated by Andrew Marr who reportedly called for ‘plays dealing with the pros and cons of independence’. Fisher scoffed that ‘a play starring Nicole Sturgeon isn’t my idea of theatrical nirvana’, revealing why, I assume, he wouldn’t have rated Borgen which precisely does star a female politician leading the daily wheeling-dealing of political life in another small nation, Denmark.

The notion that Scottish political life is unthinkable as a source for TV drama forcefully reveals how producers and commissioners, as much as viewers, are apt to be limited by their own imaginations and by the ideological forces that shape how we think about places that matter. Thankfully, such pre-conceptions are not static and the Scandindavian (and French and Italian) crimes dramas screened on BBC 4 have demonstrated how what was once unthinkable can rapidly become de rigeur. Or as Jeppe Gjervig Gram, one of Borgen’s writers, announced on a visit to Cardiff, ‘I definitely think you could do a Welsh Borgen’.

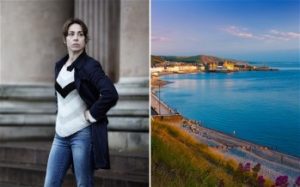

What is actually getting screened at the minute is not a Welsh Borgen but a Welsh crime drama, Hinterland [Y Gwyll] set in Aberystwyth and its outlying rural areas, and with Richard Harrington leading as DCI Tom Mathias.

Part Wallander, part Broadchurch, and overlaid by a cinematic dose of Top of the Lake, Hinterland [Y Gwyll] is a distinctly Welsh crime drama, made by Cardiff-based indie, Fiction Factory. It is currently being screened on the Welsh-language broadcaster S4C with English subtitles available for those viewers whom S4C wants to capture whose Welsh is either limited or non-existent. But an English-language version of the series is also to be shown on BBC 4 next year, alongside its existing international crime offerings, whilst a bilingual version, that offering all-too rare scenes of code-switching and other examples of how language is daily negotiated in bilingual communities, is due to be transmitted in Wales by BBC Cymru Wales in the new year. Oh, and DR Denmark have bought the English-language version too, although it seems as though the screening of the first episode at Cannes by the series’ distributors, All3Media, caught sufficient attention that the Welsh-language version may also be screened on one of their niche channels.

Exporting television matters financially and never more so than when budgets have been getting very tight indeed due in large part to cuts by government in Westminster. Co-funding, co-productions, international sales and the exploitation of rights are, in part, an answer to a major logistical problem for a small broadcaster with a limited Welsh-language audience. S4C’s recently appointed new chief executive Ian Jones, came from working as Managing Director Content Distribution and Commercial Development, International for A+E Television Networks in New York, and in the conversations and interviews I’ve conducted, this background has been repeatedly cited by TV execs as one of the reasons why the Hinterland project approached All3Media and looked to develop co-financing and an international market. International co-productions are not only a pragmatic financial solution to cuts made by a centre right and right-wing government in Westminster, but they are also potentially a way of producing something that will command interest in the broadcaster’s own schedules. This interest, I would argue, is not reducible to the interest shown by the S4C audience of the Welsh-language version. A great deal rides in such cases on whether these aspirations are realised. As Ed Thomas, Hinterland [Y Gwyll]’s executive producer and its co-creator with Ed Talfan, puts it rather colourfully:

If it fails they will say it just proves why we don’t invest into Welsh indie’s. So therefore it is a tick from the status quo and the status quo will eventually crush opt-outs and BBC Wales will really be like a Kenyan region like in the 50’s, and culturally you can forget it.

(Unpublished interview with author)

Bilingual shooting of TV drama – quite literally shooting the scene in English, then shooting the same scene in Welsh – is rare in Wales but not unique. Thomas did much the same thing 15 years ago in making Mind to Kill/Yr Heliwr, another cop show starring the late Philip Madoc. Reflecting on what has changed in the time between the two cop shows, Thomas is clear:

When we were making something like Mind to a Kill with Philip Madoc, we would strike up the police things for the Welsh version and nobody would be interested at all in seeing Welsh anywhere. The difference between then and now is that they are, but only because of other countries like the Danes and the issue of subtitling […] Half the questions everywhere, in every Q&A, has been about the Welsh and English issue, which we didn’t expect. Nor did S4C expect, they certainly didn’t expect such curiosity and warmth from All3Media.

(Unpublished interview with author)

Finding your stories and your culture to be of interest to others can be a real surprise if you’re not part of the dominant linguistic order. That’s as true for TV workers as it is for the rest of us. One of the many things that intrigues me about this production and the marketing rhetoric surrounding it, has been the cultural labour undertaken in making the series translatable to a non-Welsh audience. In some cases, this has been undertaken through explicitly genre-based discourse, situating the series through comparison with other crime shows, just as I did at the top of this blog. In other cases, it entails using looser cultural mythologies to paint a picture of a place at once new and yet already known. Take this example from the MIPCOM schedule description of the show:

Aberystwyth, Wales – a place of searing beauty: a cosmopolitan coastal university town, a mountainous hinterland of isolated farms and close-knit villages. A natural crucible of colliding worlds, where history, myth and tradition come face to face with the modern and contemporary – and a place with its own rules, a place where grudges fester, where the secrets of the past are buried deep. Into this world steps DCI Tom Mathias – a brilliant but troubled man…

While a lot of this is generic (the troubled detective is a staple of the genre), the attention to place through landscape and ideas of community chimes with much Nordic noir. A hallmark of Scandinavian crime drama – both literary and televisual- is the palpable sense of place which suffuses the narrative and which goes well beyond being the context for the plot’s action to become more of a character in itself. Such textual characteristics offer particular opportunities for international cultural translation, as Pai Majbritt Jensen and Anne Marit Waade argue, ‘Nordic Noir marks a shift in television’s drama production in which the exoticism of the settings, landscapes, light, climate, language and everyday life become promotional tools when marketing the productions internationally’ (2013: pp 259-265). There’s a fascinating negotiation of contradictions going on here as places on the one hand, are being marked and shot as distinctly local in order to cut through in the globalised TV industry, whilst on the other, their aesthetic sensibility (wide angle shots cinematically showing bare and evocative landscapes, for example) come to be increasingly seen as a measure of their transnational appeal.

Perhaps most striking though is the bilingual titling of the programme. In interview, Thomas recounts how the decision to brand the series internationally as Hinterland [Y Gwyll], ‘came from a conversation about if we were making a Japanese and English co-production you would probably keep Hinterland and then underneath a very nice little topography in Japanese and it would be a selling point.’

An appealing notion, this meant that the original title for the Welsh-language version – Mathias (the detective’s name) was ditched in favour of Y Gwyll, a Welsh word loosely meaning the glow of twilight, thus:

Y Gwyll, that’s as close as Welsh gets to Japanese and it is un-pronounceable, but it is actually very poetic…so we managed to get on the international version that branding everywhere, so even though it is sold in the international language it will be Hinterland [Y Gwyll] all the way through. Now that might be a small thing for a lot of people but to us it is capitalising on the interests that people took in the Welsh language.

(Unpublished interview with author)

Here, the fact that the Welsh language is unknown to most people outside of Wales provides the solution to the series’ own problem of cultural translation within an Anglo-dominated global TV market. That solution entails drawing on other explanatory mediations of otherness (highlighting the use of subtitles in Nordic noir dramas, for example) in order knowingly to mould the perceptions (and possible misconceptions) of an audience of buyers and commissioners. In the process of making the supposedly strange world of Wales sufficiently familiar to these audiences, one can’t help wondering however, whether and how Wales will be defamiliarised to the audience at home. Ed Talfan who directed some of the episodes, recently talked about his surprise at realising that the Welsh-language version held a greater otherness for him as someone who is a Welsh-speaker but who tends to think through the medium of English. Speaking personally, there is something slightly uncanny in watching the series’ complex mix of cinematic styles and Welsh cultural references, as if I’m watching it not only through my own eyes but also through those of a non-Welsh audience, wondering whether they’ll “get it” whilst simultaneously being faintly appalled at myself for thinking that matters at all. When I talked about this the recent bilingual English-Russian Topographies of Popular Culture conference in Finland, I was met with effusive responses of ‘but that’s how we feel too when we think of you watching Nordic crime!’, evidence that what Wales can learn from Nordic noir is a good deal more than how to tell a good crime story artfully.

Ruth McElroy is Reader in Media and Cultural Studies at the University of South Wales where she is co-director the Centre for the Study of Media and Culture in Small Nations. She is co-editor of Life on Mars: From Manchester to New York and with Steve Blandford and Stephen Lacey is series editor of Contemporary Landmark Television (University of Wales Press). She is currently working with Steve Blandford and Caitriona Noonan on examining the cultural and industrial impact of the BBC’s Roath Lock studios in Cardiff Bay.