Donald Trump’s recent announcement of his intention to seek the Republican nomination for the US presidency in 2024 was a far cry from the spectacle of his first run. The familiar bluff and bluster remained but Trump’s blonde golden child, Ivanka, stayed away, and the event was transported to the former president’s happy place, his Mar-a-Lago estate, laden with the symbolism of a Florida retirement rather than of a celebrity businessman dipped in gold on New York’s Trump Tower escalator. This was no longer spectacular fodder for the news cameras. Even Fox News cut away from Trump’s speech, and it was reported that Rupert Murdoch had pulled the support of News Corp from a 2024 bid, advising Trump in what must surely have been a ketchup-throwing meeting. Various Fox News hosts had already begun hinting that Republicans needed a new way forward, and their disappointing mid-term election results prompted a cover of the New York Post mocking Trump as ‘Trumpty Dumpty’ in freefall as a vote-loser. All’s fair in political and media oligarchies.

Donald Trump took the presidency in 2016 through a persona spun from real-estate mogul to The Apprentice’s business empire CEO and that was primed for an American electorate drunk on celebrity. Neal Gabler described Trump as ‘the Kardashian of politics’ as he brought the circus to town in the mid-West and for a national audience on television. Daniel Boorstin’s idea of the ‘pseudo-event’ concocted only for the purpose of media attention seemed to predict its pinnacle in Trump who conducted his presidency with a constant eye on the television moment. Yet the medium has proven a fickle friend. Trump’s position as controlling partner seemed to wane in 2020 when his attempt to divert attention from tear-gassed Black Lives Matters protestors with a bizarre bible-holding TV-op resulted only in a split-screen clash of potent imagery, and when Trump’s rambling COVID briefings and advice to inject disinfectant prompted cable news channels to cut away from the events, eventually forcing Trump to abandon the briefings altogether.

But the story of the relationship between Donald Trump and television was never about Trump alone, nor solely about a news agenda. My edited volume American Television during a Television Presidency shows the pervasiveness across television of not only the documenting of the political and broader culture exploited by the former president, but of responses to it. While Trump attempted control of the medium, television wrestled it back through dramas, late-night satire, science-fiction, animation and comedies that critiqued a corrupted system and national divisions that had exploded in the hands of Donald Trump. Even as he revelled in his status as the black-hatted villain in the background of fictional scenarios – or of an insurrection that played out on TV – as audiences we’ve been treated to some incredible television during a period that stands as one of the medium’s most politically engaged.

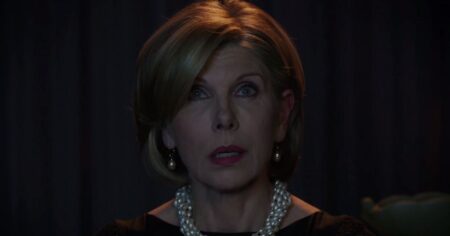

The drama of the Trump era that perhaps most directly digs into the politics of the time and its multiple effects on both individual and community is The Good Fight which my essay in the volume explores. My admiration remains for the show’s direct antecedent The Good Wife (2009-2016), a sleeper political drama that still seems to have evaded many and provokes my TV evangelism. It’s smart, centred around women, has a quirky sense of humour and should have perhaps borrowed and revised the cable tagline into ‘It’s TV. It’s not HBO’ as it proved so ably that the networks were capable of making ‘quality’ drama. The Good Wife also had two key components that it transported to The Good Fight: its inspired writing-producing team of Robert and Michelle King, and the US political arena as its central locale. The local politics of Illinois in the former series spreads out into topics of immigration, surveillance, gun control and the power of social media companies, but is catapulted in The Good Fight into culture wars, racial inequalities, sexual abuse and the Washington politics under whose pitched tent they thrive, led by Donald Trump.

Yet it was never meant to be this way. The Good Fight is one of the clearest examples of a show directly impacted by the election of Trump, after which its narrative trajectory and central conceit changed overnight. The path of its first season continued to be framed by a Madoff-style scandal that left The Good Wife’s law firm partner Diane Lockhart – again played impeccably by Christine Baranski – pitching for a job rather than escaping to retirement amongst the vineyards of Provence. When the election result arrived as a November surprise during filming of the pilot, the opening scene was rewritten as a stunned Diane watching on television the inauguration of Trump, re-setting the narrative focus and tone of the first and each following season. The Good Fight is a legal drama but not as we know it. The extreme temper of the times, the show’s white, liberal protagonist landing in a black firm, and the writers’ readiness to persistently play with style to unsettle the audience’s own complacencies mean the show is perfectly attuned to its context. Political themes from the corruption of the legal system, #metoo and male political power, systemic and historical racism, and Russian election interference (‘pee tape’ included) are threaded through the seasons, as the drama in parallel considers how individuals’ private and public lives collide and clash up against broader cultural issues.

While the show is laser-focused on Trump as its ultimate target, it avoids providing any political safe spaces. The Good Fight critiques the Democrats for their unwillingness to be political street fighters, questions whether the end can justify the unethical means when the left goes radical, and suggests political engagement – of the individual or party variety – creates no saints. Diane is awoken from her Emily’s List complacency and spun towards micro-dosing, axe-throwing and underground resistance by a political culture she couldn’t have imagined and that eventually comes for her, and by a growing understanding that she will never experience the worst of it. Audra McDonald’s Liz Reddick and Lucca Quinn played by Cush Jumbo assume central positions as carriers of its core theme of America’s racial divide and the intersectional experience, as these characters negotiate each intricate and recurring complexity. Solutions are not the realm of this show. The Kings’ rapid changes of tone and mood equally find their sweet spot in The Good Fight, becoming the ideal marrying of style, form and theme as an illustration of the head-spinning chaos of both America’s 21st century politics and Trump’s narcissistic authoritarianism. Chicago experiences a biblical-like great flood, characters are caught up in dream sequences, animated video shorts explain and critique the real-life context, and Michael Sheen gorges on wine, women and drugs as a Roy Cohn-styled, ethics-free lawyer on a path of politicized destruction.

The final season of The Good Fight is yet to land in the UK, but it seems an apt time for the show to conclude; a repeat of the Trump era is an unappealing prospect on or off screen. Television, though, is undoubtedly central to the fascination of contemporary US politics, as the medium continues to document what occurred and the legacy of the political culture is injected into narratives of every genre. Contributors to American Television during a Television Presidency will be drawing on their work with additional blog posts over the coming weeks and months, including Gregory Frame and Hannah Andrews, Teresa Forde, Donna Peberdy, Oliver Gruner, Jessica Ford and Aimee Mollaghan. They’re all brilliant, so do please check out their posts. Enjoy!

Karen McNally is Reader in American Film, Television and Cultural History at London Metropolitan University. Her most recent books are American Television during a Television Presidency and The Stardom Film: Creating the Hollywood Fairy Tale. Her interest in the recent presidency extends to a special issue on ‘Donald Trump, the presidency and the media’ published in European Journal of American Culture in June 2022. Karen’s research focuses on ideas around American identity, history and politics as they relate to Hollywood film and American television. She is currently working on a volume on narratives about the female experience of inequality and abuse in Hollywood and a monograph on Lana Turner.

References

Daniel J. Boorstin, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-events in America (New York: Atheneum, 1962)

Neal Gabler, ‘We All Enabled Donald Trump: Our Deeply Unserious Media and Reality-TV Culture Made This Horror Inevitable’, Salon, March 14, 2016, https://salon.com/2016/03/14/we_all_enabled_donald_trump_our_deeply_unserious_media_and_reality_tv_culture_made_this_horror_inevitable/.

Karen McNally, American Television during a Television Presidency (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2022)

Lee Moran, ‘Trumpty Dumpty Torched by Murdoch Media: “Perfect Record of Election Defeat”’, Huffington Post, November 10, 2022, https://huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/trump-new-york-post-journal-slammed_n_636ca5f7e4b081630470150b.