I struggle increasingly to explain to my students the basic difference between a television series and a television serial – which is a worry, because it’s a concept that underpins much of my historical teaching on narrative and genre. It doesn’t help that any television show can also be referred to generically as a ‘series’, or that Brits have in the past used the word as a synonym for what Americans term ‘seasons’ – though we do now seem to be buying into the latter.[1] Leaving aside these semantic quibbles, the problem I have is that, while pure examples of the serial now proliferate (like everyone else, I was on the edge of my seat for each cliff-hanger episode ending of Line of Duty and Vigil, and have enjoyed the various twists and turns of Only Murders in the Building), the traditional fiction series format of closed narratives within an ongoing hermeneutic – in which the same cast of recurring characters gets into and out of various scrapes within the space of each episode – is increasingly hard to come by.

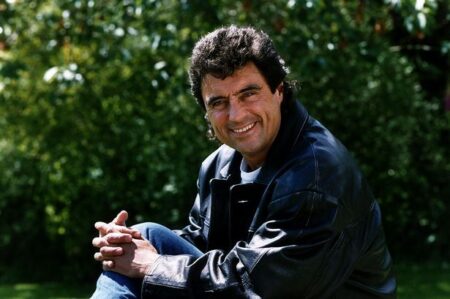

If the television play was king of the television jungle in the 1950s and 60s, the series -whether half-hour sitcom, or one-hour crime drama – was probably the defining popular format of the 1970s and 80s. I grew up watching Basil Fawlty getting into largely self-inflicted scrapes (but rarely out of them, which didn’t matter with sitcom because normal service would be resumed by the start of the next episode), or Jim Bergerac putting the criminal elements in Jersey behind bars on a Saturday evening. Jim had less than an hour to do this, which is probably why he drove his Triumph so fast. If Geraldine the goat was off her feed, Tom and Barbara would have found the solution before Burt Rhodes’ impossibly twee closing music signalled the end of the latest edition of The Good Life, and when Lovejoy was framed for selling stolen and/or fake antiques, he could be relied upon to clear his name by 9 pm.

Again.

Others have highlighted the increased serialisation of UK television fictions since the 1990s, when terrestrial broadcasters were first challenged by the arrival of satellite television, then digital, and now online streaming platforms. It is no coincidence that, around the same time, soap storylines also became more extreme, in a bid to cling on to regular broadcast audiences: plane crash, or body under the patio, anyone? Robin Nelson flagged Casualty’s employment of ‘flexi-narratives’ as early as 1993, the show’s rapid cutting back and forth between multiple open and closed story threads offering something both for regular audiences (who would appreciate the serialised content) and the casual viewer (who could tune in for the ‘accident of the week’ series element without becoming overly confused). What seems to have changed more recently is that, in the whizz-bang era of streaming platforms, the series proper is regarded as rather old hat, much as television anthology play strands were in the early 1980s. Critics and fans alike have made much of the fact that series/season thirteen of Doctor Who is a six-part serial entitled ‘Flux’, some hailing this as a return to the ‘classic’ format of the original show, in which each episode bar the story finale featured the Doctor and/or companion (as they were then termed) in mortal cliff-hanger peril. However, this ignores the fact that, back in the 1970s, viewers were given more than one story a year; usually five to six adventures, which were parcelled into four or six 25-minute episodes each. Original/classic Doctor Who would best be understood today as a series of serials (though it was the BBC’s Serials department that produced it). This format was not replicated for the 2005 relaunch, when it largely adopted a series format, initially comprising thirteen episodes a series/season,[2] while also incorporating some form of background serial element that determinedly threaded its way across the year. Under the soon-to-return Russell T[3] Davies these serial strands varied in prominence (and, to be honest, effectiveness). The whole Bad Wolf conceit of series one still doesn’t make much sense (though it did later provide Julie Gardner and Jane Tranter with a name for their production company), and Torchwood was essentially a promo for the soon-to-launch sister show the following year (and I always preferred Sarah Jane Adventures). However, the frequent mentions of Mr Saxon in series three did actually provide some hints as to the eventual return of the Master. These serial strands became more pronounced and significant under new showrunner Steven Moffat in the 2010s – but then casual viewers began complaining that they didn’t like having to concentrate so much on what was going on with Madame Kovarian and River Song, indicating that at this time an audience still existed for more straightforward series fare.

Today, even the television ‘series with serial elements’ format (as I try to explain it to my students), which used to provide viewers with the best of both worlds, seems to have fallen into bad odour. We all loved Merlin,[4] but its replacement, Atlantis, didn’t last nearly as long, despite switching more clearly into serial gear for its second season. It was surprising, then, when Chris Chibnall announced that his first year as Doctor Who showrunner would comprise entirely self-contained, episodic narratives, with nary a two-parter. It was less surprising that he switched back to the RTD/Moffat formula for his second outing (and we all know how that turned out…), and the decision to make his farewell season a pure serial can perhaps be read as a sign of the times. Even Disney+ behemoth The Mandalorian received vaguely negative reviews when some of the narratives in season one didn’t feel sufficiently serialised for a streaming service, Mando getting into and out of an expensive CGI action-packed scrape by the end of each episode without moving any closer to uncovering the mystery of Baby Yoda’s origins (or even its name). Presumably showrunner Jon Favreau had simply been watching too much Lovejoy, because season two featured a far greater number of cliff-hangers – AND revealed that the little green thing is called Grogu.

Sorry; spoiler alert.

The Disney+ practice of ‘dropping’ new episodes on a weekly basis could, in theory, accommodate the series or serial equally well – much as traditional broadcast television always did. In the UK, it is noticeable that the BBC usually opts to make entire seasons of its more series-oriented content available on iPlayer immediately after the first episode has been shown (e.g. sitcoms such as Ghosts), whereas fresh instalments of serials like the afore-mentioned Line of Duty and Vigil only become available after transmission. There is a sense here that a serial is seen as a quality dish – something that is worth waiting for, and should be savoured over time – whereas the series is designed for the ‘as much as you can eat’ crowd, like some ghastly, congealed Pizza Hut buffet [5] that is guaranteed to leave the consumer feeling bloated.

But surely this thinking is a little wrong-headed? Shouldn’t a good series episode be like a tasty sandwich, or something nice in a baguette? Enough to fill you up and keep you going until something more substantial comes along? No; better a baked potato. Baked tatties are more substantial; they fill a hole, but can have a variety of fillings – and that’s what series television does, at its best: the same basic set-up every time, but with room for variation.

These food-related analogies may be somewhat generalised; admittedly, I haven’t had my dinner yet. And I do fancy a nice hot spud. But looking back, who would want to binge on serials like I, Claudius, Edge of Darkness, or The Singing Detective? Well, I would now – but that’s only because I already know how they end, and have them all on disc. When they were first shown, the pleasure of watching was knowing that one had to wait a whole week to find out what happened next; the ‘to be continued’ element that rarely featured in series television (unless it was a special end-of-series two-parter; there’s Lovejoy again). That is what made a single, 50-minute slice of serial so special, and is also presumably what platforms like Disney+ and BBC iPlayer have picked up on, in their different ways.

So, where does that leave the television fiction series? In its pure form, it is increasingly hard to locate. For sitcoms, at least, the unstoppable juggernaut that is The Simpsons lumbers on, and in Britain Not Going Out, in which Lee Mack gets into (but, like Basil, seldom out of) scrapes on a weekly basis, continues its lengthy run. However, many sitcoms now regularly dabble in serial content. The most recent series of Ghosts included multiple storylines in each episode, some closed, some open, in order to accommodate its wide ensemble of characters. These included an over-arching storyline in which lead character Alison and husband Mike dealt with the unexpected arrival of Alison’s hitherto unsuspected half-sister, and some rare (for sitcom) character development for Simon Farnaby’s Julian, the trouserless Tory MP who has gradually grown from a self-serving narcissist to being quite a helpful chap (who saw that coming?).

As for that old stalwart, the episodic crime drama series, we will always have Midsomer Murders. Probably. But it is noticeable that new episodes often now crop up individually, perhaps filling a gap between the termination of one Sunday evening serial and the commencement of another, rather than spreading their wings in a full season of their own. It is almost as though ITV is embarrassed by it (or perhaps by series TV in general), preferring to put its money into endless true crime miniseries[6] that can be stripped across the week.

At the time of writing, I am awaiting the second episode in the latest run of Shetland, which is a case in point. The show began in 2013 with a two-part murder mystery (rather like Silent Witness, which is effectively a series of two-part stories, spread across consecutive evenings), and the second season followed with three more-two-parters, in each of which detective Jimmy Perez took just one week to solve a mur-dah and, resolution provided, we all went to bed happy (except Jimmy, who seldom smiled). Then, for series three, the programme morphed into a single six-part serial. Now, that confused me. Partly because I was expecting more two-part stories – and partly due to a rather unhelpful gap in transmission between the second and third episodes (thank you, FA Cup) – I couldn’t help feeling that the resolution to episode two was a bit, well… lacking.

D’oh.

True, I become more easily confused as I grow older, and may soon genuinely struggle to keep up with serial narratives at all – much like those who have to re-watch all six series of Line of Duty three times in order to fully comprehend the latest developments. Ah, well. I can always seek refuge in old episodes of Lovejoy on Drama,[7] lamenting (to anyone who will listen) the days when executives still knew how to make decent TV – and we always got out of scrapes in time for bed.

After nearly seven years of getting Salford students (and staff, tbh) out of scrapes on a (more than) weekly basis, Dr Richard Hewett is now Senior Lecturer in Contextual Studies for Film and Television at University of the Arts London. You are correct: he really did deserve the promotion. Dr Hewett has contributed articles to The Journal of British Cinema and Television, The Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Critical Studies in Television, Adaptation, SERIES – International Journal of Serial Narratives and Comedy Studies. His 2017 monograph, The Changing Spaces of Television Acting, was published in paperback form last year. For further information on academic publications, see here.

Footnotes

[1] Blu-ray releases of old series of ‘classic’ Doctor Who, for example, are packaged as ‘Complete Seasons’ – possibly to avoid confusion with the ‘Complete Series’ releases of ‘nu’ Who. Sigh.

[2] This was reduced to twelve for the Capaldi years, then ten for Whitaker; how much sharper than a serpent’s tooth are BBC Wales’ budget cuts…

[3] There’s no full stop. Davies won’t use one, because the ‘T’ doesn’t actually stand for anything.

[4] Apart from the ending, which I’m sure was just as traumatic for young viewers as Blake’s 7 (another series with serial elements) had been for me back in 1981.

[5] Other ghastly, congealed buffets are available.

[6] This is another confusing term for students. A miniseries is of course a short serial, and not really a traditional series at all. Sigh again.

[7] Now I think of it, I’ve got most of them on DVD already. Happy days!

What a wonderful piece! Don’t get me wrong – I like a drama series with a bit of an ongoing narrative and development as per British video series of the 1960s and 1970s like “Callan”, “Public Eye” and “Upstairs Downstairs”, and also the 1980s landmark import of “Hill Street Blues”. But I do miss the general ‘story of the week’ approach which was always satisfying for many format dramas and comedies – possibly why I’ve valued things like “Shakespeare & Hathaway” so highly in recent years (although being stripped, that was more ‘story of the day’). I think there’s room for both approaches.

And – yes – fond memories of “Lovejoy”. Particularly that very first series with its toned-down versions of some of the novels which made such stylish and engaging viewing. Nice to know that it’s still being enjoyed out there in televisionland.

Many *many* thanks for such a great read. Much appreciated! 🙂

All the best

Andrew

Many thanks, Andrew! Yes, the first series of Lovejoy was by far the best; it had a little (but not much) more of the crime genre grit present in Gash’s novels. And I should have mentioned that daytime TV now provides more of a home for traditional series fare than prime time; hopefully we’ll have a new series of Father Brown soon…