There are only two possible conclusions from listening to [Trump’s] folly: either the President actually believes what he is saying, in which case he is crazy, or he does not, in which case he is engaged in the most cynical attack on American democracy ever to come from the White House.

— Author, editor, and journalist, Susan B. Glasser, 3 December 2020 (The New Yorker)

The vast majority of people are beyond the point of caring whether or not Donald J. Trump is crazy or just profoundly cynical now that he’s no longer president. The half-century parasocial relationship that he’s enjoyed with his fellow Americans continues to wind down, but it’ll never be as intense, all-consuming, and codependent as it was during his four years in office.

The 3rd and final act of what might be considered The Trump Show began with the protagonist’s highly choreographed escalator ride with third wife, Melania Knauss Trump (m. 2005—present) at Trump Tower on 16 June 2015 when he formally announced his presidential candidacy. Few Washington politicians and pundits took this real estate developer turned reality television star seriously at that point.

Act III climaxed in a 16-minute flurry of breaking news announcements from 11:24 a.m. to 11:40 a.m. ET on 7 November 2020 when many of the major journalistic organizations in the United States—CNN, NBC, CBS, MSNBC. ABC, The Associated Press, and Fox News—projected former vice president, Joe Biden, the winner of the 2020 presidential election.

True to form, Trump tried to spin and sue his way out of what is his greatest setback. He had already survived two divorces, 26 sexual misconduct accusations, six hotel and casino bankruptcies, 3,500 lawsuits past or pending, a presidential impeachment, and now an election defeat that epitomized the reality TV trope of humiliation as entertainment for hundreds of millions of viewers all around the world.

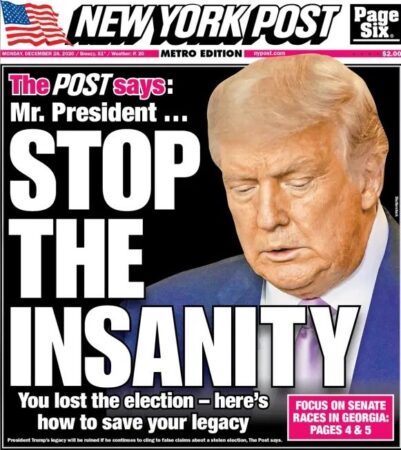

Donald Trump reflexively cried foul, claiming the election was rigged, while pursuing and losing 59 straight state and federal legal challenges from election day, November 3, until the December 14th electoral college certification of Biden’s win. What a glutton for punishment. Trump huffed and he puffed on Twitter, but still let his own media narrative spin out of control.

The more Trump ranted, raved, and tweeted, the more tone deaf, misguided, and desperate he appeared. Despite threatening his political allies to keep them in line, and intimating that he might run again in 2024 as a face-saving maneuver, Donald Trump’s irrelevancy grew more apparent with each new conspiracy theory he spun. For all intents and purposes, The Trump Show had finally jumped the shark.

Trump’s evolving persona has always been the stuff of smoke and mirrors. Some claim his behavior is textbook sociopathic. Still, his slowly dwindling base of supporters finds his public performances charismatic; they believed his tweets told it like it is until he was banned from the platform. Nevertheless, most people haven’t a clue as to what Trump is really like behind closed doors. He’s less enigmatic than a reincarnation of the classic 19th century American booster businessman turned showman politician.

Trump’s first appearance on prime-time TV in the U.S. was in a brief cameo role during the last season of CBS’s The Jeffersons (Season 11, Episode 9 entitled, ‘You’ll Never Get Rich’) in 1985 when George (Sherman Hemsley), Louise (Isabel Sanford), and Florence (Marla Gibbs) travel to Atlantic City for a brief vacation. Over the next two decades, another three dozen television and film walk-ons helped flesh out his ersatz public image as a successful real estate visionary and captain of industry and commerce.

A Cross-Section of Donald Trump’s TV and Movie Cameos (3:36):

By the time reality TV mogul, Mark Burnett, cast Donald Trump to play a caricature of himself as a ‘master of the universe’ business tycoon on The Apprentice (NBC, 2004-2017), he was well into Act II of The Trump Show where his efforts as president and CEO of The Trump Organization had already shifted much more towards building and monetizing his own brand than concentrating solely on its original mission of real estate acquisition and development.

The publicly known version of Donald Trump’s life story can be framed within the classic three-act structure of narrative fiction beginning with Act I—the setup including the core dramatic conflict leading to—Act II—the moving middle of developmental plot points and finishing with—Act III—the resolution and coda (Field).

The Trump Show was always all about whether Donald would grow up to be a ‘winner’ or a ‘loser’ to quote his most primal and habitual way of describing and categorizing people. His defeat in the 2020 U.S. presidential election answered what was for him his most elemental existential question once and for all.

Frontline: ‘The Choice 2020’ (PBS, 22 September 2020) – Sequence: ‘How Childhood and Military School Shaped Donald Trump,’ 6:45):

cstonline.netvimeo.com/504753153

Act I of The Trump Show starts with Donald’s origin story and the formative impact of his parents, Fred and Mary; followed by his meteoric rise during the 1970s and 1980s after his hard-driving father appointed him president of the eponymously named, Fred C. Trump Organization, in 1971.

Act I culminates in Donald facing the professional equivalent of a near-death experience in 1990 when the now retitled Trump Organization is pushed to the brink of financial collapse, largely as a result of his miscalculation of developing three outsized casino hotels in Atlantic City, thus overextending the family business by an estimated $4 billion including $800 million for which he himself was personally liable (Flitter).

Act II involves a roller coaster of ups and downs that eventually leads to Donald Trump’s midlife comeback. The Trump Organization tenaciously regains its footing throughout the 1990s because of the financial intervention and backing of his then-retired father, Fred, who dies in 1999 at the age of 94, leaving Donald as the lone remaining patriarch of the family.

Donald Trump next completes the redirection of The Trump Organization to licensing the Trump name nationally and internationally on dozens of real estate properties owned by other developers as well as scores of ancillary ventures, including Trump Magazine, Trump Books, Trump University, the Donald J. Trump Signature Collection (menswear and accessories), Donald Trump The Fragrance, Trump Shuttle, Trump Restaurants, and Trump Productions, which produced the Miss USA and Miss Universe Pageants along with The Apprentice (NBC, 2004-2010) and its spinoff, The Celebrity Apprentice (NBC, 2008-2017), among many other side businesses that together proved to be essential sources of income for him and his family’s corporation.

Suffice it to say that by the first decade of the 21st century, Donald Trump’s fortunes were again on the upswing. Via The Trump Organization, he was realizing his domestic and global aspirations of becoming a celebrity brand. Cut to award-winning filmmaker, Errol Morris. Beyond his brilliant portfolio of two-dozen original feature-length documentaries, he is a producer-director of a handful of short films, television series and miniseries, and over one-thousand TV adverts.

Morris’s commercial work is what led Laura Ziskin, producer of the 74th annual Academy Awards ceremony on ABC in 2002, to commission him to shoot and edit what turned out to be a short four-minute and fifteen second Oscar-friendly compilation of several dozen celebrities interspersed with a few regular people naming their best loved films and briefly adding funny, offbeat or touching quips about them.

Not surprisingly, Donald Trump was invited to be one of the interviewees. The four-second segment of him that Morris included didn’t in fact mention his favorite movie. It was more a side comment that Trump made during the interview that fed into his ongoing carefully cultivated public image as a dominating real estate developer and ruthless business tycoon. He said, ‘seeing King Kong try and conquer New York,’ a fleeting statement that was at once playful and self-aggrandizing.

Looking into Morris’s custom-made Interrotron months before in New York, Trump had actually chosen Citizen Kane (1941), Orson Welles’s thinly-veiled Roman à clef about newspaper baron, William Randolph Hearst, as the film he most identified with and admired. He discussed what Citizen Kane meant to him for nearly a half-hour with Morris.

Outtakes of Donald Trump Conversing About Citizen Kane (3:33)

Over the course of their conversation, Trump talked excitedly about Kane’s ‘great rise’ and ‘modest fall,’ making certain to point out that it ‘wasn’t a financial’ but ‘a personal fall.’ Towards the end Morris asked him, ‘If you could give Charles Foster Kane advice, what would you say to him?’ Trump smiled self-assuredly and answered instantly, ‘Get yourself another woman.’

Trump never mentioned Kane’s megalomania, his acquisitiveness or the miserable way in which he treated people. Trump’s response was instead delivered without a hint of irony. He was by then well practiced in what he preached, having engineered two successive divorces from ex-model Ivana Zelníčková Trump (m. 1977—div. 1992) and actress Marla Maples Trump (m. 1993—div. 1999) that were lavishly covered in the tabloids during the 1990s.

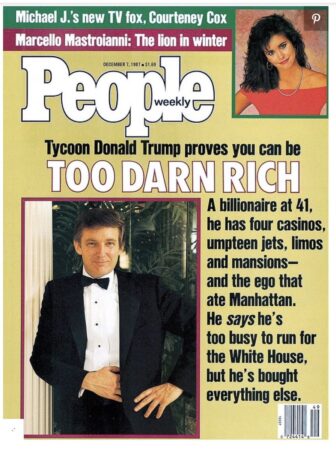

The national bestseller, Trump: The Art of the Deal (1987), made Donald a household name in the U.S., but his 14 seasons of hosting first, The Apprentice, and then The Celebrity Apprentice, catapulted him into the uppermost echelon of television stardom and international fame. Always a transmedia production, The Trump Show gained added synergy on 4 May 2009 when Donald tweeted for the first time: ‘Be sure to tune in and watch Donald Trump on Late Night with David Letterman as he presents the Top Ten List tonight!’

Ever the self-promoter, Trump’s favorite medium of choice was and still remains television over the half-century that he’s doggedly created and grown his own celebrity brand. His last appearance as host of The Celebrity Apprentice was the 16th of February 2015 or precisely four months before he officially declared his candidacy for president in the aforementioned kickoff event at Trump Tower where he promised to ‘Make America Great Again’ (MAGA).

Little did anyone realize at the time that Act III of The Trump Show was off and running and would resolve itself some five-and-a-half years later. All that is left to play out after his fateful 2020 election defeat is the coda, which is beginning to eerily resemble the tragic finality of Citizen Kane.

Much like Charles Foster Kane, Trump’s political ambitions were born out of his early privilege, hubris, and conceit. He first flirted with the notion of a presidential run as far back as the waning years of the Reagan administration while he was on tour promoting Trump: The Art of the Deal.

There is a well-worn American maxim that the person who holds the presidency mirrors the state of the union and its people. Like all clichés, there is a scintilla of truth buried in this old saw, even in the anomalous case of Donald Trump. During his four years as president, he was regularly characterized as an ‘ugly American’ in the domestic and international press (Karabell; Luce; McGeough; Meaney and Wertheim; Milbank).

The ugly American stereotype dates back to the 19th century finding its first printed expression in Mark Twain’s tongue-in-cheek travelogue, The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrim’s Progress (1869). More often than not, the ugly American label has been applied to U.S. travelers who behave badly in other countries. In this context, they act impolitely and thoughtlessly; they are loud, graceless, disrespectful, blundering, and ethnocentric.

Eugene Burdick and William Lederer’s best-selling political thriller, The Ugly American (1958), about U.S. diplomatic failures in Southeast Asia, forever mainlined this characterization into everyday parlance. The press’s use of this pejorative description to call out Donald Trump is the direct result of his abrasive and boorish personal style as well as his ‘America First’ foreign policy pronouncements, which echo similar sentiments expressed by U.S. isolationist-oriented Americentric movements that held sway for a time during first the post-World War I and then pre-World War II eras.

Trump’s updated version of Americentrism is much more extreme than mere American exceptionalism, which emphasizes the country’s uniqueness, although this latter perspective can sometimes devolve into an inflated sense of national superiority as well. 21st century Americentrism or Trumpism is not so much a political philosophy as a neo-nationalist style of governance that is marked by authoritarian populism, strong nativist tendencies, and provocative acts of illiberal democracy.

What is called Trumpism today is not an aberration in American politics. Its roots can be traced back to early populist uprisings during the Jacksonian age (1825-1849) with its most recent expressions being the 1958 creation of the John Birch Society, an extreme conservative advocacy group; the political ascendancy of evangelical Christian Americanism during the last 25 years of the 20th century, and the recent increased visibility and growth of white nationalism.

What is unique about Donald Trump’s presidency is the degree of influence that these radical far-right movements exerted on a U.S. head of state who is much less ideologically-motivated than they are. Trump’s main concern is instead ‘winning’ at all costs and by any means necessary. His realpolitik even degenerated into stealpolitik in the aftermath of the 2020 presidential election. Trump was the F-You president for his truest believers; a wrecking ball to the democratic political system and a backstop to any sort of left-leaning change.

Moreover, Trump’s assault on the truth is widely recognized. According to a running tally kept by The Washington Post, Trump averaged nearly 20 false or misleading public statements per day throughout the course of his presidency (Kessler). In turn, the verb, ‘gaslight’ gained added currency and a new appreciation because of Trump’s relentless efforts to control his own narrative and impose a self-serving alternate reality onto the rest of America.

‘Gaslighting’ is derived from the 1938 play, Gas Light, and its 1944 filmic adaptation, Gaslight, and it describes how a narcissistic bully can bend, reshape, and generate a highly manipulative parallel way of seeing and feeling that leaves his or her victims questioning their own sanity. Hence, Donald Trump proved to be the ultimate bully in the presidential pulpit. He masterfully created a sense of collective psychosis throughout his presidency that engulfed and monopolized the attention of his supporters and opponents alike.

In retrospect, Trump took a homegrown style of booster rhetoric that dates back to the early 19th century in the United States and amplified it to a next generation 2.0 degree through his use of digital media. Trump’s ‘tall talk’ on all forms of 21st century TV and Twitter transformed a vaguely anachronistic mode of commercial speech that confuses ‘present and future’ by conflating ‘fact and hope’ as a way of reaching, motivating, and persuading his followers (Boorstin 296).

What people from other countries and Trump’s political foes take ‘for lies and braggadocio’ is ‘simply’ him ‘speaking in the future tense, asserting what cannot yet be disproved.’ Donald Trump is the product of a profit-driven rhetorical tradition that rarely ‘confines’ itself ‘to demonstrable facts.’ He ‘seldom’ says ‘less’ than he ‘intends’ (Boorstin 296). The nagging question from the outside is whether or not Trump sometimes even ‘gaslights’ himself when he spins his latest sales pitch, conspiracy theory or personal attack on his enemy du jour to his base of supporters.

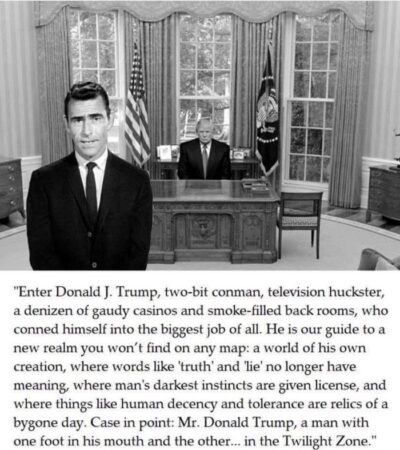

Fig. 2: Viral Trump Meme (Image created by David Mikkelson of The Sunday Herald [Glasgow, Scotland] and published on 16 January 2017; caption later written by J. Paul Nadeau and posted @jpaulnadeau Twitter and Instagram on 16 October 2019)

The 2020 coronavirus pandemic compressed years of change into months and assured that Donald Trump would be a one-term president because of his administration’s gross mishandling of its greatest challenge. Likewise, Forbes’s senior editor, Dan Alexander, reported that COVID-19 affected ‘Trump’s net worth,’ causing it to plummet from ‘$3.1 billion’ to ‘$2.1 billion’ (2 April 2020). Alexander’s investigative digging similarly uncovered that Trump owed ‘at least $1 billion’ and has ‘$900 million in loans coming due’ over ‘the next four years’ (16 & 19 October 2020).

Furthermore, Trump faces serious legal prosecution in at least a handful of suits now that he’s left office. For example, the Manhattan district attorney is investigating The Trump Organization on bank and insurance malfeasance and falsification of business records. The New York state attorney general is also pursuing him for criminal tax fraud.

On a personal level, E. Jean Carroll has a defamation lawsuit pending against Trump, who she alleges raped her in the winter of 1995-1996, as does Summer Zervos, a former contestant on The Apprentice, who claims that he sexually assaulted her in 2007. Both of these plaintiffs contend he has since defamed and harassed them. And Trump’s niece, Mary, is suing him and his siblings for largely cutting her deceased father, Fred Jr., out of the family estate when her grandfather, Fred C. Trump Sr., died. A dozen other lawsuits involving corporate finances, various sexual offenses, and obstruction of justice while president are also in the works.

Donald Trump is facing a reckoning of historic proportions. The vulnerable position he finds himself in is why he was so reluctant to leave the protection and executive privilege that the White House afforded him. The thin ice he’s traipsing on the financial, legal, and personal fronts is an overriding reason why he spared no effort and went to such extremes to stay in power.

Consequently, The Trump Show’s coda is even more toxic, unhinged, and tragic than Citizen Kane’s. Rather than pulling off the comeback of a lifetime as the self-styled escape artist extraordinaire, Trump is left licking his wounds and weighing his shrinking prospects as America’s crazy ex-boyfriend ensconced in his Palm Beach Xanadu.

Ten social media platforms (Discord, Pinterest, Reddit, Shopify, Snapchat, Stripe, TikTok, Twitch, Twitter, and YouTube) have issued either permanent or temporary restraining orders on Trump’s online broadsides or fundraising activities for inciting the January 6 mob riot on the Capitol where five people lost their lives. The Trump Organization too is in retreat, losing lucrative contracts from numerous civic and commercial partners including New York City and the PGA (the Professional Golfers’ Association of America).

Trump is currently a much diminished figure in American business and political life who discredited and disgraced himself by the mendacity and incompetence he showed the world with his post-2020 election power grab. His approval rating is now in a death spiral even falling well below Richard Nixon’s at a comparative point in their respective presidencies (‘How Popular Is Donald Trump’). Only recency bias would delude anyone into believing Trump still has a bright future as a GOP kingmaker or a Lazarus-like MAGA presidential candidate.

One-term presidents rarely leave much of a footprint. Donald Trump’s celebrity brand as a business prodigy turned political savant is also irreparably damaged. More importantly, the Republican sycophants who used him for political purposes over the past four years are finally glad to see him leave Washington.

Likewise, his blindly ambitious legislative co-conspirators who enabled him with their procedural theatrics during Biden’s certification as president-elect on January 6 and 7 are also turning the page. They no longer calculate that it is politically expedient for them to pretend they shared his nonstop complaints about a rigged election after his latest super-spreader TV spectacle, which ended in a mob stampede on the U.S. Capitol while they were in session. Trump may also face criminal charges and civil liability for his role in this fiasco.

There is a neuropsychological condition called dysmetropsia (informally known as ‘Alice in Wonderland syndrome’) where those people afflicted see and feel distortions in their visual and experiential perceptions. It is most commonly evident in misperceiving objects (as being smaller, bigger, closer or farther away than they are) but it can impair a sense of time as well. For a majority of Americans, the four years of the Trump presidency felt like a hard slog that dragged out in dog years. They now can step through the looking glass, breathe a sigh of relief, and wish him the longest of goodbyes.

The 19th century American realist author and literary critic, William Dean Howells, once mused, ‘What the American public wants is a tragedy with a happy ending’ (Wharton 65). Act III of The Trump Show is playing out as a national tragedy that echoes in living memory the sorry downfalls of both Senator Joseph R. McCarthy (R-WI) and President Richard M. Nixon. These two politicians did a great deal of short-term damage to American democracy, but the longer view of their respective histories suggest that Trump’s virulent influence on the country might be much less permanent than some pundits have predicted.

Donald J. Trump has recently been impeached an unprecedented second time followed by the requisite Senate trial. The recklessness he again demonstrated in breaking sacred democratic norms provides a fitting albeit profane denouement to The Trump Show. Trump’s performance in elected office—like McCarthy and Nixon’s before him—remains a climactic cautionary tale for the nation. Act III of The Trump Show is thus bittersweet, but it concludes happily nonetheless with his slow fade out in the rearview mirror.

Gary R. Edgerton is Professor of Creative Media and Entertainment at Butler University. He has published twelve books and more than ninety essays on a variety of television, film and culture topics in a wide assortment of books, scholarly journals, and encyclopedias. He also coedits the Journal of Popular Film and Television.

Works Cited

Alexander, Dan. ‘Donald Trump Has At Least $1 Billion in Debt, More Than Twice the Amount He Suggested,’ Forbes. 16 October 2020 at https://forbes.com/sites/danalexander/2020/10/16/donald-trump-has-at-least-1-billion-in-debt-more-than-twice-the-amount-he-suggested/.

______________. ‘Trump’s Net Worth Drops $1 Billion as Coronavirus Infects the President’s Business,’ Forbes. 2 April 2020 at https://forbes.com/sites/danalexander/2020/04/02/trumps-net-worth-drops-1-billion-as-coronavirus-infects-the-presidents-business/.

______________. ‘Trump Will Have $900 Million of Loans Coming Due in His Second Term if He’s Reelected,’ Forbes. 19 October 2020 at https://forbes.com/sites/danalexander/2020/10/19/trump-will-have-900-million-of-loans-coming-due-in-his-second-term-if-hes-reelected/.

Boorstin, Daniel J. The Americans: The National Experience. New York: Random House, 1965.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. New York: Dell Publishing, 1979.

Flitter, Emily. ‘Art of the Spin: Trump Bankers Question His Portrayal of Financial Comeback,’ Reuters. 17 July 2016 at https://reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-trump-bankruptcies-insig-idUSKCN0ZX0GP.

Glasser, Susan B. ‘The President is Acting Crazy, So Why Are We Shrugging It Off,’ The New Yorker. 3 December 2020 at https://newyorker.com/news/letter-from-trumps-washington/the-president-is-acting-crazy-so-why-are-we-shrugging-it-off.

‘How Popular Is Donald Trump?,’ FiveThirtyEight. 20 January 2020 at https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/trump-approval-ratings/.

Karabell, Shellie. ‘Donald Trump: The New Ugly American?,’ Forbes. 8 January 2018 at https://forbes.com/sites/shelliekarabell/2018/01/08/donald-trump-the-new-ugly-american/.

Kessler, Glenn. ‘Fact Checker Analysis in 1,372 Days, President Trump Has Made 26, 548 False or Misleading Claims,’ The Washington Post. 22 October 2020 at https://washingtonpost.com/graphics/politics/trump-claims-database/.

Lederer, William J., and Eugene Burdick. The Ugly American. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1958.

Luce, Edward. ‘The Heyday of the Ugly American,’ Financial Times. 19 October 2018 at https://ft.com/content/6aca4250-d30c-11e8-a9f2-7574db66bcd5.

McGeough, Paul. ‘Ugly American Donald Trump Is About to Enter the White House,’ The Sydney Morning Herald. 17 January 2017 at https://smh.com.au/world/donald-trump-the-ugly-american-is-about-to-enter-the-white-house-20170117-gtssb5.html.

Meaney, Thomas, and Stephen Wertheim. ‘When the Leader of the Free World Is an Ugly American,’ The New York Times. 9 March 2018 at https://nytimes.com/2018/03/09/opinion/sunday/donald-trump-foreign-policy.html.

Milbank, Dana. ‘Trump, the Caricature of the Ugly American, Demeans Us All,’ The Washington Post. 2 June 2017 at https://washingtonpost.com/opinions/trump-the-caricature-of-the-ugly-american-demeans-us-all/2017/06/02/d2043a70-478a-11e7-bcde-624ad94170ab_story.html.

Post Editorial Board. ‘The Post says: Give It Up, Mr. President—For Your Sake and the Nation’s,’ New York Post. 27 December 2020 at https://nypost.com/2020/12/27/give-it-up-mr-president-for-your-sake-and-the-nations/

Trump, Donald, with Tony Schwartz. Trump: The Art of the Deal. New York: Random House, 1987.

Twain, Mark. The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrim’s Progress. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1869.

Wharton, Edith. French Ways and Their Meaning. New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1919.

WOW, trump should have been a magician. He had so many people fooled for 4 years, but now we are seeing that he is all smoke and mirrors.