Many years ago, whilst preparing to teach British Cinema History at LJMU, under the brilliant, but now sadly departed Nickianne Moody, i was tasked to research the history of British Music Hall. The main thrust of the module was to show how British cinema was the product, not of the theatre, but of the music hall tradition and working-class popular culture. Theatre, it was argued, aspired to ‘art’, it was bourgeois, and it was elitist, whereas British cinema’s origins and expression derived, in large part, from popular entertainment for the masses – music hall. In America, cinema owed much the same to the vaudeville tradition.

It was a typical Marxist approach to the study of British cinema and one that argued not for art but for popular culture. Apart from some early token resistance from a Reithian BBC, early British TV, especially when commercial TV emerged, looked to the masses, and was awash with actual examples of music hall acts and influences making the transition to television. Fiske, in his study, Reading Television (2004), observes how Light Entertainment television “inherits many characteristics (and some personnel) from the circus/music hall tradition.” Although many of the traditional music hall acts or personnel have disappeared completely in their original form, some have remained, but in different form – they have mutated or been brought up to date. Fiske observes how television’s origins in the music hall traditions have been “obscured or transformed”. However, and more significantly, the sensibility of music hall has remained, in fact, the sensibility has potentially seen a resurgence. Fiske observes how, as a result of its music hall origins, television challenges “the dominance of the bourgeoisie”; and as with music hall it recognises “cultural tensions” rather than ignoring or attempting to hide them behind a screen of ‘art’, and television’s origins in the music hall tradition can be seen in the way it “brings to the forefront of our cultural stage the ephemeral and verbal arts of a subordinate culture.” (2004, p.126). In many respects, contemporary, deregulated television highlights this sensibility and these dynamics even more effectively than before. Music hall was ‘deregulated’ entertainment for the masses. It offered something that high art ignored or avoided. It made normal working-class performers celebrities in their own right; it was cheap to produce, but potentially lucrative; It often flirted with the scandalous, and It offered a variety of different acts for niche interests. This arguably describes the contemporary television landscape and its variety and content available across deregulated, multi-channel TV.

These ideas and approaches have always been in the background throughout my time researching and lecturing on various aspects of television. As such, there have been numerous occasions where I have longed to apply the filter of British music hall tradition to examples of British TV. But how and where can this influence, history, or sensibility still be seen? How is the tradition or ethos of music hall, this form of deregulated entertainment manifested in this new era of television – if at all? What or who are the inheritors of this history and of these traditions?

All of these ideas came to the foreground again recently as a result of my watching CBS Reality’s True Crime offerings, a genre that has largely been seen as ‘pulp’, sensationalist, voyeuristic, exploitative, and of having a tabloid sensibility (Murley, 2008), a genre often accused of pandering to a morbid fascination with depraved humanity, of using crime, and particularly murder, for entertainment purposes. The reasons for these views are due to True Crime’s elements of performance.

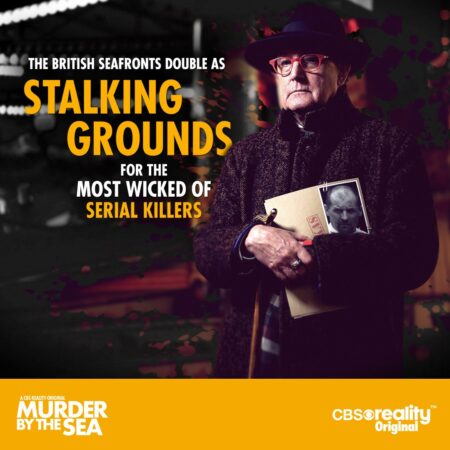

One particular programme hosted by CBS Reality’s True crime collection is Murder By The Sea (2018 -). This is a True Crime programme that positively promotes murder as an end-of-pier show. Murder By The Sea is particularly notable where the music hall tradition is concerned due to its use of paraphernalia, modes of address, and iconography traditionally associated with garish seaside attractions, end-of-pier shows, and traditional working class leisure and entertainment.

Each episode is introduced and narrated by Geoffrey Wansell, a True Crime writer, who delivers an eery, almost melodramatic account of events to the audience, and who can be seen dressed in a long dark heavy overcoat, a black fedora hat, black leather gloves, a cravat-like scarf, and carrying an ornate walking stick. This is the start of the performance of true crime. Each episode, includes re-enactments, often depicted through a variety of distorted lens and canted angled shots, backed by distorted sound effects, and ends with an aerial shot of Blackpool Tower (I wonder if the Blackpool Tourist Board are happy with this?) accompanied by a sort of distorted fairground music.

In fact, this performance element – the performance of crime, and, of murder – has long been a convention of the True Crime genre, and its performance element has often been closely tied to mass popular culture and popular entertainment whose roots can be traced back to music hall. BBC Four’s factual Crime and Punishment season, which was repeated recently over Lockdown, included the programme The Story of Capital Punishment (2011), which drew attention to how at the last public execution in Britain in 1868, onlooking crowds cheered and sang the popular music hall song Champagne Charlie as the convicted murderer was hanged. Here, the connection between the actual crime and punishment and the performance/entertainment element of British music hall is made explicit.

With its use of end-of-the-pier show iconography to illustrate its tales of true crime and murder (in various episodes, a Punch and Judy show is blatantly used as a background) CBS Reality’s programme Murder By The Sea (produced by Barking Mad Productions) seems determined for audiences to make a similar connection. Performance, popular cultural practices, and entertainment are elements that inform the genre and it is the element of performance which often attracts criticism. Interestingly, the type of criticism that is aimed at True Crime (depraved behaviour as entertainment) was aimed at music hall and it is a criticism that has equally been applied to Reality TV.

It can be argued the most obvious contemporary examples of British TV programmes carrying on the music hall tradition, in spirit and attitude if nothing else, are those certain types of Reality TV shows (Britain’s Got Talent (ITV, 2007 -) is the most obvious example) where ideas of art and bourgeois culture are not only largely absent, but avoided. Their target audience is as distinctive as music halls was. I argue for certain forms of Reality TV because the music hall tradition is as much a sensibility, an attitude, as anything else.

Richard Baker, in his study of British Music Hall: An Illustrated History (2014), states how “music hall had no place for reticence: it was downright, it shouted, it made noise, it enjoyed itself and made the people enjoy themselves as well.” British music hall gave “the British working class its own form of entertainment and its own breed of stars”. More significantly, music hall was often accused of pandering to “the lowest propensities of depraved humanity” (Baker, 2014). Sound familiar?

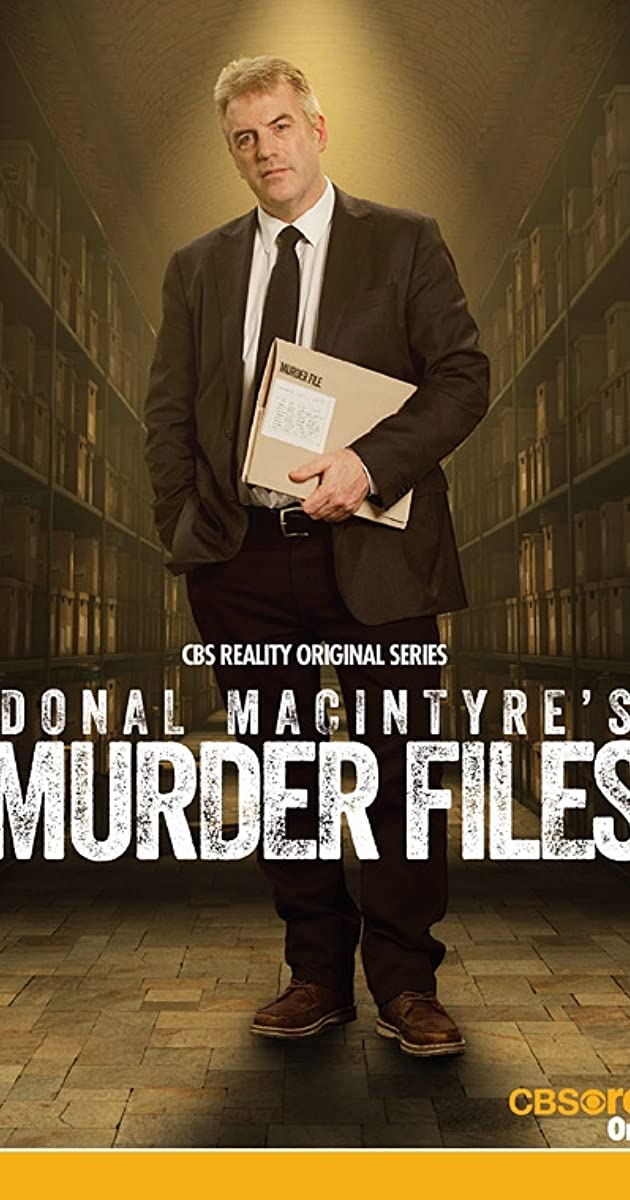

In some ways, Murder by The Sea is typical of CBS Reality’s thematic approach to True Crime TV. Programmes such as Killer Clergy, Killer Cops (Who’d have guessed?), Teens Who Kill, Fatal Vows (you can imagine), and Murderers and Their Mothers are just a few of the True Crime offerings by CBS Reality which focus on a demographic of murder and murderers. The Freudian Murderers and Their Mothers is a programme that comes as close as it can to blaming mothers for the actions of their murderous offspring. To add to this list are two series hosted by Donal MacIntyre (Donal MacIntyre’s Murder Files, and Donal MacIntyre: Unsolved), a former pin-up boy for BBC’s tentative venture into Investigative Journalism programming (MacIntyre Investigates, BBC1, 2002-03), and which led to criticism that Current Affairs programming was descending into tabloid sensationalism. MacIntyre, himself, was at the centre of an investigation during his time at the BBC where he was accused of falsifying video evidence and misrepresentation (it was settled out of court). Ekström (2002) describes how these types of programmes were always “oriented towards the construction of exciting, dramatic and astounding stories” whilst at the same time expressing “special claims to knowledge and truth.” (2002, p.271)

Jean Murley, in her study The rise of true crime: 20th-century murder and American popular culture (2008), observes how performance and sensationalism are key conventions of True Crime in all its forms – magazines, books, film, TV, and more recently, the Internet – and she cautions how “the way real murders are turned into stories (in the mass media) are very troubling in these times.” (2008).

Similarly, Tanya Horeck, in her study, Justice on Demand: True Crime in the Digital Streaming Era, (2019), and in her discussion on the entertainment values and phenomenon of the My Favourite Murder podcast (listeners/fans refer to themselves as ‘Murderinos’) describes the “commodification of true crime as a multimodal entertainment ‘experience’.” (2019).

Performance, therefore, is important to the True Crime genre, and how we understand, accept, or reject the genre. Murley observes how although the True Crime genre presents non-fiction narrative treatments of actual crime, fictional or dramatic techniques are always involved. Similarly, Seltzer, in his study True crime: Observations on violence and modernity (2007) describes how “True crime is crime fact that looks like crime fiction.”.

These dramatic or performance elements, as seen in True Crime television, can be seen in the evolution of the True Crime Genre, which Murley argues starts with the True Crime Magazines of the 1940s and 50s. By the 1960s True Crime Magazines had started depicting lurid or semi-pornographic images on their covers to entice readers and to sensationalise real accounts. These images very often had little connection to the stories and accounts contained within the magazine’s pages, but they illustrated, in more ways than one, the ways in which True Crime juxtaposed factual events with dramatic elements, and tabloid sensationalism. True crime magazines mixed real photographs and real accounts with artistic illustration and dramatic language, thus creating a hybrid experience where fact mixed with fictional techniques.

This is a convention that has seemingly transposed itself to television.

In True Crime television, the performance or dramatic elements are most visible through the technique of dramatic re-enactment. Dramatic re-enactments (performance) can be troubling where factual content is concerned, and especially where the reporting of murder is involved. Citing the ground-breaking documentary, The Thin Blue Line (Morris, 1988) as an example, Murley explains how dramatic re-enactment is usually used to “fix a moment in time” and show what actually happened. However, the way dramatic re-enactments are used can call into question the truth or the factual events. Dramatic re-enactments, as with True Crime as a whole, change a reality that has happened. These re-enactments work alongside other performative and narrative conventions which we have come to expect from True Crime. Murley describes how True Crime stories are commonly structured around one killer or one murder event; They always provide a psychological portrait of the killer usually with the aid of official documents or testimony from an expert. This last feature is aimed at creating ‘closeness’ or engagement by the viewer/reader with the murderer. Next, there are graphic depictions (re-enactment) or description of horrific acts/murder aimed at ‘distancing’ the viewer from the murderer. These stories commonly revolve around a four-act structure and incorporate techniques borrowed from fiction.

As Murley points out, the way real murders are turned into stories for the purpose of entertainment is significant. True Crime narratives reflect the tensions and preoccupations of the culture or indeed the sensibility that produce them. Yet, for all the accusations of True Crime being voyeuristic, exploitative, and of having a tabloid sensibility, Murley points out that “at its best, True Crime questions its own motivations and reasons for being.” (2008).

Murley argues that “True Crime is a way of making sense of the senseless”, but for whom? In these respects, the performance element of True Crime is therefore potentially significant. As with Fiske’s observations, television in general, the music hall tradition, and CBS Reality’s Murder by The Sea, True Crime television essentially performs difference. It performs difference through the ephemeral and verbal arts of a subordinate culture.

Kenneth A Longden is a Lecturer in Television and Media, University of Salford, and a Fellow HEA.

References

Ekström, M. (2002). Epistemologies of TV journalism: A theoretical framework. Journalism, 3(3), 259-282. https://doi.org/10.1177/146488490200300301

Fiske, J. (2004). Reading Television. Routledge.

Horeck, T. (2019). Justice on Demand: True Crime in the Digital Streaming Era. Wayne State University Press.

Murley, J. (2008). The rise of true crime: 20th-century murder and American popular culture. ABC-CLIO.

Seltzer, M. (2007). True crime: Observations on violence and modernity. Taylor & Francis.

Thanks for the great blog Kenneth. There is some Music Hall stuff in my recent CST blog on comedy, cstonline.net//cstonline.net///from-monty-python-to-music-hall-by-jonathan-bignell/ and I would argue that this adoption of vaudeville can be thought about through the lens of Adaptation Studies: cstonline.net//cstonline.net//doi.org/10.1093/adaptation/apz017

Thanks Jonathan. I am flattered. I know your work really well and it has always informed my lectures. Thanks for the link and for taking the time to give me some feedback

Fascinating stuff Kenneth – two arenas which I’m only vaguely aware of, and the linking of these two forms made for a very enjoyable and enlightening read. Many thanks! 🙂

All the best

Andrew

Thanks Andrew. Sorry for the delay, i have only just seen this. I have to say, i have enjoyed reading your contributions of late. Thank You!