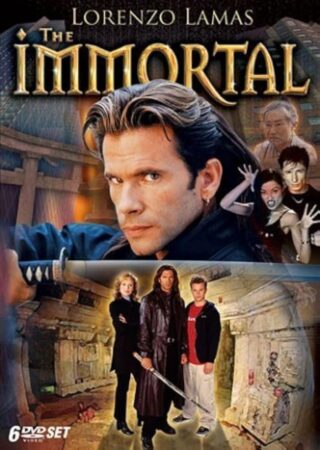

Those of you who have been following my work for awhile may have realised that I have a certain fondness for analysing short-lived, unstudied and often poorly-regarded media texts. Not just limited series, mind you, but series that were cancelled after a series or two (or even earlier) often show a great deal about specific cultural and industrial moments. It is in that vein that I recently began watching The Immortal (first-run syndication, 2000-2001). For those unfamiliar with the series, it follows Rafael ‘Rafe’ Cain (Lorenzo Lamas), an English sailor (with an American accent) from the sixteenth century who was shipwrecked in Japan during its initial opening to trade. He marries a local woman, has a child with her, begins training under a local martial arts master and eventually meets a fellow castaway, Goodwin (Steve Braun). After his wife is killed and daughter abducted by a demon, Mallos (Dominic Keating), Rafe acquires immortality through unexplained means– we are shown a beam of energy or light hitting him, so it is possibly somehow angelic or divine– and begins a campaign which is a mixture of revenge, rescuing his daughter and protecting the world from a nebulous, Satanic thousand-year plan. As the series begins, it is the year 2000 and Rafe and Goodwin ally with Dr Sara Beckman (April Telek), a paranormal expert looking for scientific ways of finding and fighting demons.

Already, some of the issues with the premise are clear. Though Rafe is treated as more an adoptee into Japanese culture than an appropriator of it, having a white, pseudo-Christian ‘Chosen One’ using Japanese cultural traditions (including martial arts) can be read as problematic.[i] Prusa (2016) argues that revenge as a motivation for characters is a trope common to Western and Japanese media, so the overarching plotline can perhaps be read as a parallel or blend rather than an appropriation. In 1.21, it is stated that Rafe’s marriage to a local Japanese woman, Makiko (Grace Park), led to her being shunned for marrying a foreigner and both being banished. This, along with the reason for Mallos abducting Rafe’s child being tied to her being mixed-race, however, illustrating that racism in particular is tied to demons and humans alike. This implies that the production team are aware of the potential appropriative issues in the premise and are utilising them for critique. Because it ended after a single series, however, it is unclear how this aspect would have developed.

Sword and science (and a skosh of sorcery

The series’ premise also overlaps with many of its contemporaries– Highlander (syndicated, 1992-1998) is the most common comparison, but the series’ attempts at flippant humour, often comedic minor antagonists and its frequent embrace of its own campiness can also evoke Buffy the Vampire Slayer (WB/UPN, 1997-2003) and Angel (WB 1999-2004). The Hong Kong-style wirework used in some of the martial arts also evokes Kung Fu: The Legend Continues (syndicated, 1993-1997) while the paranormal aspects driven by a female scientist suggests links to the X-Files (Fox, 1993-2018). These similarities, attempted on a first-run syndication budget, seem to be one of the reasons why the series was unsuccessful. Yet, as was– and, to an extent, is– common to the time, though the series is an American production it filmed primarily in Vancouver with a brief excursus to Prague, leading to a particular form of hybridisation that Tinic (2005) discusses is common to such mixed production contexts. I would extend that here to argue that such a hybrid form of mixed accents, locations and styles is also something of a genre trope for many first-run syndicated series.[ii]

Thus, the series encapsulates many of the strengths and weaknesses inherent in first-run syndication. There has been very little academic work on syndication from an industrial standpoint– Clarke (2023) is the only substantive work I have found thus far (though feel free to suggest work in the comments) so much of my analysis is speculative. First-run syndication was originally positioned as allowing for edgier or more distinctive content than would otherwise be allowed under a network (Clarke 2023). In this, it can be thought of as a forerunner to quality television and streaming. And while, in some cases, this could be successful (e.g., the sociocultural and sociopolitical critiques of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine [1993-1999] and Babylon 5 [1993-1998]) because it was sold to individual stations who would (in theory) develop a library of content, it did not have the financial backing of a network series and was often difficult to find. Times, days and even stations would vary from week to week and could be pre-empted by sports or other forms of special content. This, naturally, made it difficult to acquire and maintain a regular audience, which would negatively impact the revenue generated from advertising during episodes. It also means that first-run syndicated series tended to eschew serialisation (Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and Babylon 5 excepted[iii]) in favour of an episodic format. Yet, unlike network-based episodic series which often build upon characterisation and relationships (Cardwell 2019), because syndicated series could easily lose multiple episodes those characters and relationships were often slow to change to avoid confusing the audience. These limitations also impact overall worldbuilding, as the audience cannot be counted upon to have access to every episode. The diegesis is built slowly, vaguely and rarely allowed to change in any significant way beyond that which can be included in a recap or clip.

Going back to The Immortal, all of this is quite evident. While the characters do develop and there are a handful of character-driven episodes where the regular and recurring cast get to shine (e.g., 1.12 and 1.16), there is very limited change. Rafe’s mission, though occasionally questioned, remains the same. The heroes are often tempted, usually by sex though occasionally by vanity, but only ever waver rather than fall. There is some depth given to the regulars, but it tends to be done through flashback episodes rather than developing over the course of multiple episodes of interactions and experiences. The characters’ pasts are thus fleshed out but their present remains broadly unchanged over the course of the single series. Because the characters’ lives have been long, however, and the series embraces humour and the episodic format allows for disconnectedness, it can encompass and subvert a variety of genres from period drama to spy fiction to soap opera to psychodrama. This does allow for at least some limited experimentation in form as well as aligning with the satire of more powerful places and associated texts (including those supported by a network) that Tinic (2005) notes is common to Canadian-produced media. The positioning of government and law enforcement– in the diegetic-US and abroad– as being either aligned with demons or as being laws unto themselves does allow for some moral grey to be introduced, but the regulars comment upon it rather than directly engage in such moral ambiguities themselves.

Though the series plays with the idea that demons can choose to reform or seek redemption, this is undercut every time by it being part of a trap. Demons are diegetically considered irredeemably evil and feed on pain, hatred and similar emotions, so there are no moral grey areas regarding killing them; they were once humans, however, which suggests backstories and depth for them even without directly engaging in such. While this positioning is used for occasional critique, usually of fascism, oppression (including by police forces), prejudice, abuse of power by socioeconomic and political elites, gender-based violence and the like,[iv] there is also a surprisingly prescient awareness of the potential use of the internet in spreading what can broadly be considered to be hate speech.[v] Though mostly-unformed due to the series’ short run and industrial limitations, the demonic world appears to be riven with hierarchies which can mimic either a royal court or a business; in many respects, that concept makes for a more interesting premise, with elements of that premise seen in some of the other series with which The Immortal is compared. Unbound by humanity, the demons also seem much more charismatic and (in my view, admittedly) much more interesting to watch, often switching easily between sadistic manipulation, overt sexuality, jealousy– Mallos’ hatred of Rafe and his family seems a mix of explicit racism and, as performed, envy over Rafe’s experience of love– and iterations of the trickster archetype. Yet because they diegetically lack the capacity for redemption, they also are restricted in their growth.

Though Rafe does send Mallos back to Hell– although demons can return to Earth from there in some instances[vi]— and his daughter is returned, a different demon makes a claim to her at the end of the final episode. So, much like the series’ demons and other paranormal entities, The Immortal was left incomplete and unable to change to any significant degree. It does, however, provide a window into not only a cultural moment but into an industrial context that, though now gone, still resonates throughout the contemporary mediascape. I would therefore argue that the series, as a representative example of and along with first-run syndication, is a critically important part of media heritage. It may not be immortality, but it has definitely had a lasting impact.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Dr Melissa Beattie is a recovering Classicist who was awarded a PhD in Theatre, Film and TV Studies from Aberystwyth University where she studied Torchwood and national identity through fan/audience research as well as textual analysis. She has published and presented several papers relating to transnational television, audience research and/or national identity. She is currently an independent scholar. She is under contract with Lexington/Bloomsbury for an academic book on fictitious countries and Palgrave for a book on Canadian crime dramas. She has previously worked at universities in the US, Korea, Pakistan, Armenia, Ethiopia, Cambodia and Morocco. She can be contacted at tritogeneia@aol.com.

References

Cardwell S (2019) In small packages: Particularities of performance in dramatic episodic series. In L F Donaldson and J Walters (eds) Television Performance. London: Red Globe Press. 22-42.

Clarke M J (2023) First-Run syndication and unwired networks in the 1980s: Viacom’s Superboy and Buena Vista TV’s DuckTales. Television & New Media 24(2): 221 –241.

Prusa I (2016) Heroes beyond good and evil: Theorizing transgressivity in Japanese and Western fiction. Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies 16(1): 1-30.

Tinic S (2005) On Location: Canada’s Television Industry in a Global Market. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Weissmann E (2012) Transnational Television Drama: Special Relations and Mutual Influence Between the US and UK. Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan.

[i] Though his surname is suggestive, Rafe is not directly connected to fratricide. It is likely more the idea of wandering eternally.

[ii] New Zealand was the other location of choice for first-run syndication, e.g., Xena: Warrior Princess which I discuss here.

[iii] The former having brand recognition and the latter marketing itself as a ‘novel for television’– prefiguring quality TV strategy (Weissmann 2012)– likely helped acquire and retain audiences even when episodes were irregularly scheduled.

[iv] Also included as demonic are unions and street mimes, however. The Romani, much like in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, are shown as engaging in protective magic while being oppressed by elites (1.20-21).

[v] The use of satanic television and music leading to mind control is so exaggerated in specific episodes (1.7 and 1.15) that they are clearly satire. Especially the part where demons find disco to be torture.

[vi] The change in villain may also be related to Keating becoming a series regular on Enterprise (UPN 2001-2005) as I have discussed elsewhere.