Nothing else but ‘NADA’?

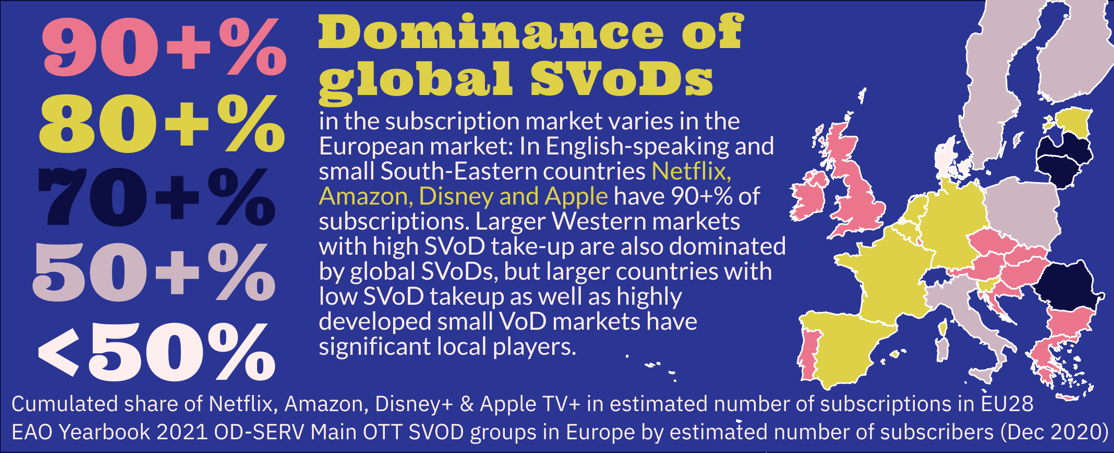

Fig. 1: Estimated share of subscriptions to Netflix, Amazon, Apple TV+ & Disney+ in EU in December 2020.

Be it bingeing, the business of streaming or trends in audiovisual storytelling, much of our understanding of video-on-demand cultures builds on research about US-American platforms; particularly Netflix. And this is understandable, given that Netflix has been the driver of the transformation from broadcast to video-on-demand and is both perhaps the most global producer and distributer of content (Lobato and Lotz 2020, p. 132), as well as a significant player locally with distinct localized catalogues and specific strategies for investing into local content (Lobato 2019). If we look at Europe, Netflix is estimated to account for 39 percent of subscriptions to Video-on-demand (EAO Yearbook 2021). If we add in Amazon, Disney and Apple, we arrive at 81 percent of subscriptions to VoD in the EU for US-based global players. So, focusing on ‘NADA’ helps us capture as well as compare major trends in the VoD market, such as their different localization strategies.

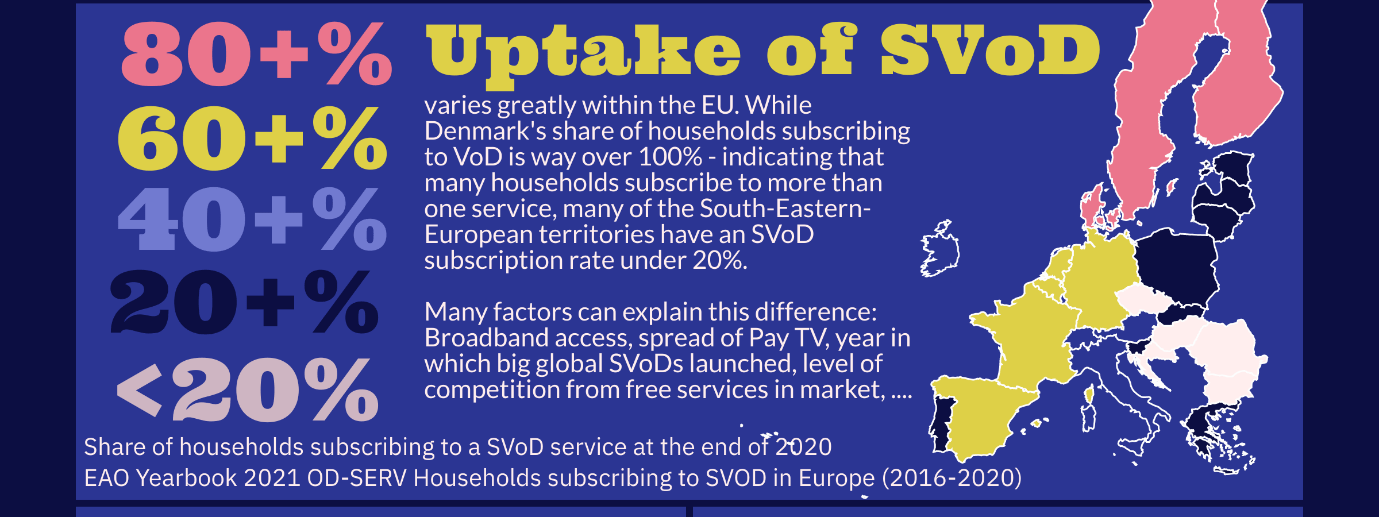

At the same time, such a focus on the global players makes us blind to a lot more diverse and perhaps conflicting trends going on in local markets. As argued by Tom Evens and Karin Donders (2018) the resilience of broadcasters and cable providers is often underestimated, not least because the European market in its diversity is so fundamentally different from the US market, which most of the globally operating services originate from. Therefore, this blog-post looks closer at data on the market penetration of global SVoDs in Europe and discusses eight media-systemic factors that shape the diverse VoD landscapes we see in Europe.

Fig. 2: Cumulated share of Netflix, Amazon, Disney+ and Apple TV+ in the EU based on estimated subscription numbers (Dec 2020)

While dominating the SVoD markets in Europe’s English-speaking countries, South-East-Europe and Western Europe, NADA have a far weaker base elsewhere. In the Nordics, Baltics, Italy and the bigger markets in Eastern Europe, we see significant market shares of local or regional SVoDs like Viaplay (DK 22%) and TV 2 Play (DK 19%), TIM Vision (IT 16%), Go3 (LT 26%), Polsat Go (formerly IPLA) (PL 30%) or Voyo (RO 23%). How can we explain this?

How to explain the different patterns of dependency on global SVoDs in the European market?

Market maturity is one explanatory factor: In many markets in South-Eastern Europe, less than 20 per cent of households subscribe to a VoD service (as of 2020), indicating limited market potential for local players. In contrast to this, the SVoD penetration in Denmark – the most advanced streaming market in the EU (see also Grece 2021) – over 100% of Danish households subscribe to a VoD, which means that many Danes have taken out several subscriptions.

This situation allows the regional and local players Viaplay (22%) and TV 2 Play (19%) to take second and third place after Netflix in subscription numbers. Both services originate from broadcasters, which have held strong positions in the broadcasting market before. In Germany, also a relatively advanced VoD market, however, the share of local-grown SVoDs emerging from the most relevant commercial broadcasters RTL (RTL+) and Pro7Sat1 (joyn) is just 4% of households subscribing to VoD. So, other factors must be taken into consideration.

Different business models play a role in judging the development of the VoD market. Subscription is only one of the business models in VoD. SVoD accounts for 27 percent of all 2800 VoD services available in Europe (Schneeberger 2021), while the majority are actually so-called “free VoD services”, meaning that they can be funded through advertising, taxes or the license-fee. These free services often achieve a high reach in individual markets: In Denmark, for example, the public-service-broadcaster’s FVoD DRTV even surpasses Netflix in terms of weekly reach (DR Medieforskning 2022, p. 7). Looking only at subscription numbers to ascertain the development of the VoD market obscures this fact.

Both Germany and Denmark (along with many other Northern and Western European countries) have very strong public service broadcasters providing free VoD services. But market size, of course, affects how far public revenues can stretch. While the license-fee in Germany affords six different free VoD services by PSM players, DR is the only entirely free full VoD service in Denmark (though there are also free local news services funded by the Danish media tax). The small size of the Danish advertising market also puts a limit to how many services can be funded by advertising; which makes it less surprising to see that the commercial PSM TV 2’s VoD platform is mainly subscription funded with ads only present for those customers with the cheapest subscription.

In 2019, the expenditure on TV advertising in Germany was 4.8 billion Euro, only 3.5% lower than in 2016. While the German commercial players like RTL or ProSiebenSat1 are investing in streaming and in-stream ad revenues are growing, the online ad-business is still much smaller and cannot make up losses from broadcast ads (see: Telkmann 2021). This puts the commercial players in the big markets in the difficult position of continued dependency on linear ad-income, while ambitious VoD strategies do not necessarily lead to commercial success. In addition to that, the share of Pay-TV revenues in the AV markets of Germany as well as the other big nations Italy, Spain and France are low compared to their importance in Europe’s small markets (EAO Yearbook 2021), indicating a limited readiness of the viewers to pay for content in the countries spoilt for free media choice.

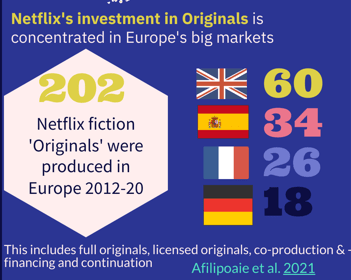

Fig. 5: Top countries for number of Netflix Originals produced between 2012 and 2020 (source: Afilipoaie et al. 2021)

Local investments by global VoDs is another factor where market size becomes relevant for explaining differences in the European market. With their local ‘Originals’ Netflix and Amazon and in the future also Disney+ (Ramachadran 2021) hope to become attractive to the viewers and the investment increasingly also extends to non-fictional content (Elmes 2022). But again, these efforts differ across markets according to size, affluence and export potential of content. We find this reflected for example in Netflix’s investment into local original content; mostly pooled in Europe’s Western large nations (Afilipoaie et al. 2021). HBO Max’s recent announcement that it would halt original productions in the Nordics and Central and Eastern Europe, but keep up production in the big markets Spain and France, affirms these hierarchies (Ravidran 2022). HBO’s strategic shift also points to the fragility of the global player’s (costly) localization in the context of rising inflation and declining investor confidence in global streamers. Investments by global SVoDs are still dwarfed, though, by commissions from local broadcasters, particularly PSM (Fontaine 2022).

A factor connected to levels of localization are regulatory conditions. Following the 2018 revision of the Audiovisual Media Service Directive, some European countries have implemented direct investment obligations for VoD services (see: Iordache et al. 2022). One could expect that these will further drive local content production and acquisition that may make global services more attractive to domestic audiences. High local content quotas are cited as a reason for HBO’s continued investment in France (Ravidran 2022), where SVoD services’ right to attractive windows for cinematic releases is tied to an investment of 25% of their turnover into French productions, part of which is direct investment (Cabrera Blázquez et al. 2022, pp. 39–40). Other countries are equally bold: Italy requires VoDs to invest 17% of their revenues in content from local independent producers, which can also be fulfilled by acquiring locally produced content. This figure will increase to 20% from 2024. It is too early to tell whether a broader scope of local content on global services in Italy resulting from the investment obligations may cause a rise in Netflix, Amazon, Apple and Disney+’s shares of the Italian SVoD market.

Still, there are territories neglected by ‘NADA’. A lack of local content is a factor that was already predicted to make Netflix less relevant to Central and Eastern Europe than domestic players like Voyo when Netflix first expanded there (DTVE Reporter 2016). A preference for content dubbed into local languages adds to the expense of localization for global platforms (Imre 2018). Given that Poland and Romania have opted for comparably less demanding investment obligations, it is also not to be expected that global platforms expand their offer of local content there in the future. HBO and its early focus on Eastern European originals used to be an exception here (Hansen et al. 2021), but the merger between Warner and Discovery has put a halt to these efforts (Ravidran 2022). Since the European Audiovisual Observatory does not report subscription numbers for HBO Go, the service is not part of the assessment above, making it hard to judge how much of an impact its local content has had on subscription numbers in the CEE. After all, HBO Europe’s original content has been criticized for offering only a superficial and commercially driven engagement with the region’s national cultures (Imre 2018).

Local telecommunication providers’ role as purveyors of package deals for pay TV and subscription services is another factor to consider when looking at local players’ relative strength. Polsat Go (formerly IPLA), which achieves a 30 per cent share of households subscribing to VoD in Poland, is owned by Cyfrowny Polsat, the satellite TV supplier with the highest market share in Poland (3.8 million subscribers as of 2020). Access to Polsat Go is included in the subscription to Polsat’s TV package. The TV package is not only the gateway to their own channels, which achieve a daily market share of 25 percent (2020) making it the most important commercial broadcaster on the Polish TV market, but it also provides access to many other Polish TV channels and premium channels such as HBO. Furthermore, Polsat offers bundles with subscriptions to global services such as Disney+, Paramount+ and HBO Max included. Polsat’s strength, therefore, lies in the combination of role as provider of local content (local channels) and function as a gatekeeping platform (see: Evens and Donders 2018) that now expands from access to broadcast channels to VoDs at a stage where there is still significant development potential in the Polish VoD market (Grece 2021, p. 28).

Researching the diversity of the European VoD market: together

Comparing data on market penetration of global vs. local VoDs and exploring reasons behind the diverging patterns of development gives us an insight into the diversity of the European VoD market. Doing this diversity justice requires an understanding of Europe’s individual media systems that is attuned to the specificities of the VoD market. Efforts in gaining a comparative overview on the development of Europe’s VoD market are, however, complicated by the dynamic, local and context-specific nature of the research object.

First, we are dealing with a moving target: Numbers on subscriptions or platform use are outdated as soon as they are published, services pop-up and disappear, companies merge both on the global and local level. Keeping track and keeping a record, or better even an archive, of what is going on is essential.

Second, the transnational conversation on VoD is dominated by work on the big US-born VoDs. This is to some extent justified because the global platforms are not only taking significant market shares, but are also a research object which scholars in transnational media research all share, though it is of course looking different in all markets. Justifying the relevance of and raising an interest in what is going on behind the global frontier, is more difficult since cases on activities of local platforms within their specific contexts do not necessarily speak to each other. The streaming services of public service media (PSM) are an exception here. They have been tracked and studied, for example within the RIPE initiative for at least a decade now; united by a common concern around how PSM cope with the transformation of the media market. The development of local commercial VoD services and key gatekeepers in the specific market is less comprehensively covered, particularly when it comes to transnationally comparative perspectives.

Third, adequately covering the diverging trends on the European market and its many curious cases requires local knowledge that cannot be gained and gathered alone. Therefore, I hope that whoever is reading this blog might feel inspired to reach out, discuss cases and work together on developing and testing more hypotheses on the factors that have impacted the development of Europe’s VoD markets.

Many thanks to Luca Barra at the University of Bologna for discussing the case of TIM Vision with me and to Magda Tyzlik-Carver (Aarhus University) for helping me navigate the offer of Polsat.

Cathrin Bengesser is Assistant Professor for Digital Media Industries at Aarhus University’s Department of Media and Journalism Studies. She researches European media policy, the development of the European streaming market and transnational audiences. She is PI on an AUFF-funded (2021-23) project that studies the impact of media systemic differences on the transformation from broadcast to VoD markets in Europe. Together with Pia Majbritt Jensen, she is the co-director of Aarhus University’s Centre for Transnational Media Research.

Bibliography

Afilipoaie, Adelaida; Iordache, Catalina; Raats, Tim (2021): The ‘Netflix Original’ and what it means for the production of European television content. In Critical Studies in Television 16 (3), pp. 304–325. DOI: 10.1177/17496020211023318.

Cabrera Blázquez, Francisco Javier; Cappello, Maja; Tallavera Milla, Julio; Valais, Sophie (2022): Investing in European works: The obligations on VOD providers.

DR Medieforskning (2022): Medieudviklingen 2021.

DTVE Reporter (2016): NEM: Netflix ‘irrelevant’ for CEE.

Elmes, John (2022): Netflix plots to expand unscripted universe.

Evens, Tom; Donders, Karen (2018): Platform power and policy in transforming television markets. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fontaine, Gilles (2022): Audiovisual fiction production in Europe. 2020 Figures.

Grece, Christian (2021): Trends in the VOD market in EU28. European Audiovisual Observatory. Strasbourg.

Hansen, Kim Toft; Keszeg, Anna; Kálai, Sándor (2021): From Remade Drama to Original Crime – HBO Europe’s Original Television Productions. In European Review 29 (5), pp. 601–617. DOI: 10.1017/S1062798720001131.

Imre, Aniko (2018): HBO’s e-EUtopia. In Media Industries Journal 5 (2). DOI: 10.3998/mij.15031809.0005.204.

Iordache, Catalina; Raats, Tim; Afilipoaie, Adelaida (2022): Transnationalisation revisited through the Netflix Original: An analysis of investment strategies in Europe. In Convergence 28 (1), pp. 236–254. DOI: 10.1177/13548565211047344.

Lobato, Ramon (2019): Netflix nations. The geography of digital distribution. New York: New York UP.

Lobato, Ramon; Lotz, Amanda D. (2020): Imagining Global Video: The Challenge of Netflix. In JCMS 59 (3), pp. 132–136. DOI: 10.1353/cj.2020.0034.

Ramachadran, Naman (2021): Disney Plus Ups European Originals From 50 to 60, European Chief Reveals at Series Mania Lille Dialogues.

Ravidran, Manori (2022): HBO Max Halts Originals in Parts of Europe in Major Restructure. In Variety, 04.07. 2022.

Schneeberger, Agnes (2021): Audiovisual media services in Europe. Supply figures and AVMSD jurisdiction claims – 2020.

Telkmann, Verena (2021): Online First? Multi-Channel Programming Strategies of German Commercial Free-to-air Broadcasting Companies. In International Journal on Media Management 23 (1-2), pp. 117–146. DOI: 10.1080/14241277.2021.1963969.